‘Veggie Man’ Zooms to Kenya, Helps to Bridge Cultures

LEXINGTON, Ky. (July 10, 2020) — “Connection” is arguably Professor Michael Goodin’s favorite word. Whether it’s through his University of Kentucky coffee class, his research into plant diseases, his passion for food or his blog, The Green Orange Café, the College of Agriculture, Food and Environment plant virologist is always looking for the connection that links everything or everyone. It just takes a bit of effort and imagination to find it.

Before the pandemic struck, Goodin often took his traveling veggie show to elementary school science fairs in Lexington. There, Veggie Man, as he calls himself, encourages students to make edible art using vegetables he provides. With bell pepper torsos, cucumber heads and radish feet, the veggie people that emerge from the students’ imaginations provide the connection between plants and animals and open a discussion about basic health and biology. Goodin said the children eat this stuff up, literally, which supports a discussion of how to “magically” convert plant cells into human cells.

While the COVID-19 global pandemic has put a halt to his frequent professional and personal travels, Goodin isn’t staying idle at home. Instead, with the help of technology, he is continuing to bring important connections to the attention of young people, most recently in Kenya through the Zoom classroom of the Fun and Education Global Network. He and FEGNe founder Kenneth Monjero, a plant virologist in Nairobi, Kenya, connected through a complex network of coworkers and mentors that started with a correspondence about Monjero’s work on a cassava virus.

“Then I found out he does this science outreach education with kids, which resulted in him inviting me to meet with his FEGNe students through Zoom,” Goodin said. “I did the exact same exercise that I do with Lexington kids, and it resonated in the exact same way, because kids are kids. They’re just fascinated by stuff like that.”

Monjero, aka Dr. Fun, founded the nonprofit organization at the beginning of the global pandemic as a way to assuage children’s fears.

“My thinking was, children are wondering, ‘Is the world ending?’ Everything has closed down. Schools have closed down. There’s a kind of trauma, and nobody is responding to that,” Monjero said. “That’s what drove me to looking at children first, because if their parents are traumatized by the disease, they can forget to hold their children and make them understand. So, we can bring children together to learn that if we control this, if we put on our masks, if we stay at home, this will end, and then we’ll go back to school.”

As Monjero was beginning to structure his Fun and Education Global Network, he realized it was a good way for children to share not only local issues, but also global ones.

The scientist is passionate about empowering children and youth, as his website proclaims, “to face local and global issues boldly through networks, creativity and innovation to make the globe better than before for livelihoods.” Though Monjero started FEGNe with Kenyan children in mind, the nonprofit has now grown to include eight countries from all corners of the globe and continues to expand. Twice a week, in the morning for the eastern part of the globe and in the evening for the western hemisphere, he offers online sessions that open the world to children and introduce them to experts in wide-ranging fields, everything from medicine, nutrition and agriculture to government. He recently had the Irish and Australian ambassadors speak to the class.

“How do you divide fact from fiction? We bring in professionals to talk to children. We even got a doctor from a New York hospital to talk to the children about COVID-19,” he said. “Right now, our plan is to engage them on issues that affect them while they’re at home.”

Some of those issues concern children’s eating habits, food insecurity and food waste.

That’s where Goodin could help. He showed the students slides of food from his travels around the world.

“I said, ‘Pay attention, because there’s going to be food you’re familiar with,’ and every time one of those slides came up, you could hear the ‘Ahhhh!’” he said. “And fruits and vegetables? Whether it’s Kentucky or Nairobi elementary school kids, it’s the same. They’d rather eat cake. We’re the same the world over.”

Monjero said they wanted to bring together children who are rich or poor and from every region.

“They realize there are other children who have never eaten pizza. There are children who maybe eat meat once in two months, and there are others who get beef from the freezer and throw it away. And that drives them to learn about what affects this distribution of food. Why do you have plenty, why do I have less? And why do we need to feed the population in the future, and why we need to do more for agriculture,” he said.

Importantly, Monjero links children from different countries to work on projects together. He is now registering children to enter an Agri-COVID gardens global competition. Agri-COVID is his coined term for vegetable gardens begun during the pandemic.

“Children across the globe will be trained and mentored,” he said. “Since it’s predicted that famine will strike (some areas of the world) after COVID-19, children are getting ready to address this. Children will present their work in October during the FEGNe International Conference."

Monjero’s work excites Goodin, who strives through his coffee class, his travels and the common language of food to tear down barriers.

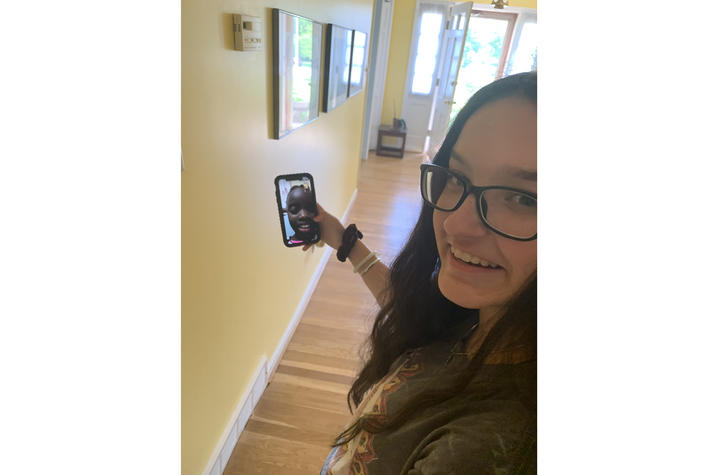

“Experiences like this can break down the stereotypes; you log into Zoom and there are kids on their computers with headsets on and microphones in Nairobi, Kenya,” he said. “I would imagine that some are unaware of similarities between here and African countries, but everything we’re doing, they’re doing. You’ve got this cultural bridging between young people that wouldn’t otherwise have happened, but for the sheltering in place. (The issues) are absolutely translatable. My daughter Sophia and Ken’s daughter Grace continue to chat via WhatsApp. American and Kenyan perspectives are connected.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.