Creating a Culture of Collaboration for Research at UK and Beyond

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Jan. 10, 2014) -- There's a proverb in the business world that says, "If you don’t know, hire someone who does."

In the world of translational research, the saying might go like something this: "If you don't have the expertise or resources, collaborate with someone who does."

The nature of translational science -- the process of turning a basic science discovery into applications for human patients -- is inherently multidimensional. Moving from the "bench to bedside" is a process that runs the gamut of biomedical research, incorporating laboratory and animal studies, clinical trials, drug and device development, regulatory issues, grant writing and more. Each step requires specific expertise, and so the process depends on interdisciplinary teams.

"Translational science is team science," said Dr. Philip A. Kern, director of the University of Kentucky Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) and the Barnstable Brown Diabetes and Obesity Center. The CCTS is funded by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Collaboration is primary goal of the CTSA, and team science is critical in addressing complex health issues that necessitate problem solving from multiple perspectives.

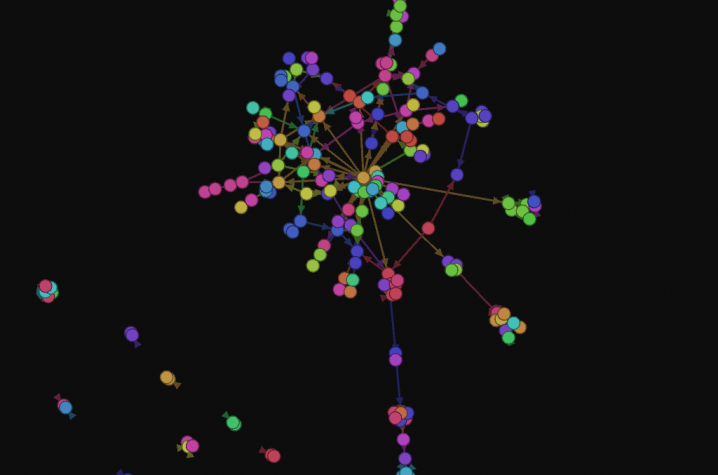

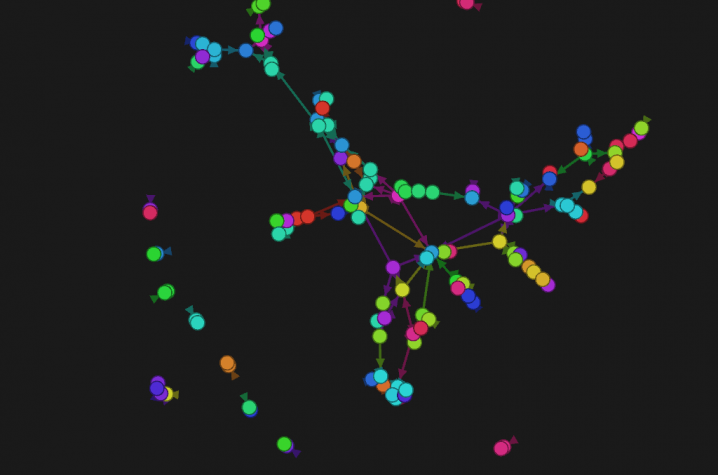

Since its establishment in 2006, UK's CCTS has worked to foster a culture of collaborative research across campus and beyond. The center directly involves more than 240 individuals from 16 UK colleges, the offices of the President, Provost, Executive Vice President for Health Affairs, Vice President of Research, and all components of UK HealthCare. The CCTS does not focus on any one particular disease or condition but rather serves as a catalyst to improve the research environment for addressing complex health issues.

The work of Dr. Moriel Vandsburger epitomizes the vital role of collaboration in translational science. A biomedical engineer, he spent the first years of his career developing novel MRI techniques in mice models. Now he's expanding that work to develop new MRI techniques to identify early stages of heart disease in high-risk populations that are excluded from existing diagnostic methods. Existing methods use contrast agents, which aren't suitable for patients with reduced kidney function. Ironically, individuals with reduced kidney function are at higher risk for heart disease. If successful, Vandsburger's techniques could potentially change how these patients are diagnosed and treated. But first he has to collaborate with physicians to translate his work from the lab to clinic.

For Vandsburger, who joined UK only six months ago, the collaborative research environment supported by CCTS is not only critical to his work but it was also pivotal in his decision to join the UK community. Amongst the many places he interviewed, Vandsburger states that UK clearly stood out because of its robust collaborative culture.

"Even during interview process, CCTS was trying to connect me with physicians," Vandsburger said. "For a biomedical engineer, there is difficulty in getting connected with patient populations. It is not uncommon to work for four to five years before gaining clinical access. At UK, it took literally four to five minutes. My meetings with physicians showed me that collaboration is not just lip service here. From the top level down, there's a lot of institutional support for what I want to do."

Vandsburger collaborates with Dr. Steve Leung, a cardiologist, to validate his new MRI technique. It uses standard clinical imaging technology and requires obtaining just one additional image, adding about 18 seconds to the MRI process. They've collected data on over 35 patients so far.

"There would be zero chance of this work happening without this collaboration, and very little chance without the CCTS," he said. " I came up with the idea, but there are about 50 people making it possible. Translational research and clinical collaboration are words that every institution likes to throw around. But here, it's real. It's something unique about UK. People see research as a team effort."

A robust collaborative culture is a valuable asset in recruiting high-level faculty committed to translational research.

"We have to make it attractive for individuals to create a cohort of investigators in a particular arena for shared activity and depth. Siloed investigators aren't going to survive," said Dr. Stephen Wyatt, dean of the UK College of Public Health and a member of the CCTS executive steering committee.

Vandsburger was recruited by Dr. Brandon Fornwalt, assistant professor in pediatrics and biomedical engineering, who says that the CCTS was one of the reasons that he decided to join UK.

"The only way to get stuff done is to work with other people who are experts," said Fornwalt. "And its especially important in the atmosphere we're in right now, when the funding has plummeted to all time lows. "

Dr. Peter Giannone, chief of neonatology and vice chair of pediatric research, was also attracted to UK's commitment to collaboration for translational science -- so much so that he brought his entire research team and their R01, a top-level research grant from the NIH, to UK from another institution two months ago. They collaborate with the departments of maternal fetal medicine, radiology, and neurology to study delayed umbilical cord clamping for prevention of intraventricular hemorrhaging in premature babies.

"It's exceedingly easy to collaborate here, and the environment is completely supportive of everything we wanted to do," Giannone said. "We want to really put Kentucky Children's Hospital on the map in terms of translational research."

The CCTS leverages its expansive research network on campus to catalyze collaboration through its Research Concierge program. Researchers can call the CCTS with any issues or questions, and they will be connected with the appropriate expert or resource.

"We are able to quickly direct investigators to what and who they need for their projects," said Elodie Elayi, director of research development at the CCTS.

The CCTS also operates an integrated Pilot Program, which supports investigators in innovative interventions and early stage and collaborative research. An interdisciplinary cohort of NIH experts reviews proposals, and awardees are supported by interdisciplinary teams that help them anticipate and address challenges to keep their projects on track.

Another hub of collaboration within the CCTS is the KL2 Scholars program, a structured program of education and team mentorship to help junior faculty obtain a career development award as an independent investigator. Vandsburger is currently supported through the KL2 program, and Fornwalt graduated from the program upon receiving an Early Independence Award from the NIH. He was the first UK faculty member to earn the highly competitive award.

"K Club," the group of KL2 scholars and mentors, meets every two weeks to discuss their projects and workshop their grant proposals. The group is diverse in terms both expertise and experience.

"It creates a lot of dialogue," said Vandsburger. "Mentoring is probably the most important aspect of developing as a scientist. Each mentor gives me a different perspective. It has fundamentally changed how I write grants and approach research."

The collaborative momentum extends beyond campus as well. The CCTS works closely other CTSA institutions such as Marshall University, The Ohio State University, Ohio University, Pikeville College, West Virginia University, and the University of Cincinnati, particularly on research efforts related to health disparities in Appalachia. The Community Engagement Core of the CCTS furthermore fosters collaboration with community partners to support research and improved health in the region.

Wyatt sees the networks of collaboration, which have grown substantially over the past five years, as fundamental in the contemporary landscape of research and healthcare.

"That's the virtue of team science - I can do 'this much', but who can do what else I need? People have their own expertise, but they need others, too. In this day and age, we need a true team approach to address complex issues."

MEDIA CONTACT: Mallory Powell, mallory.powell@uky.edu