New Research Illuminates School Staff Experiences through COVID-19

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 24, 2020) — An ongoing study led by University of Kentucky researchers is giving school staff, including teachers, a needed outlet to voice their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost 10,000 school staff across Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio have responded to a survey that aims to understand not only what COVID-19 mitigation strategies are being implemented but also how these measures impact staff wellbeing.

School staff have had a uniquely harrowing experience in a pandemic that’s turned everyone’s lives upside down. Already under-resourced, our teachers, administrators, bus drivers, dietary, facilities, and other school personnel have now been charged with bridging the gap to get our kids back in school — they are responsible for complying with COVID-19 safety protocols (including disinfecting their spaces with high-grade cleaning agents that could have health risks) and getting students “on-track” academically and socially during a global crisis through which no one has been expected to perform as usual. All of this is on top of the personal health risks to school staff during in-person instruction.

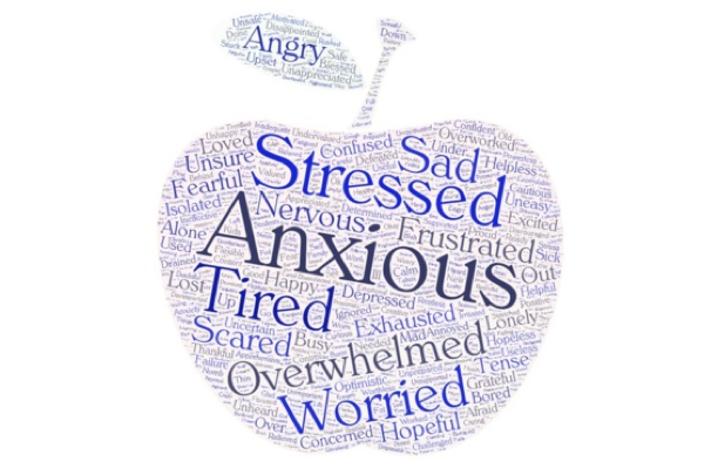

These compounding pressures played out in the survey findings: When respondents were asked what five words best characterized how they felt during the Fall 2020 semester, the most common responses were “anxious,” “overwhelmed,” “stress,” “tired” and “worry.” The vast majority of school staff — more than 70% — also indicated that “difficulties were piling up so high that [they] could not handle them.”

The study is the brainchild of Erin Haynes, DrPH, who wears many hats. She is the Kurt W. Deuschle Professor of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, chair of the UK Departments of Epidemiology & Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, and deputy director of the UK Center for Appalachian Research in Environment Sciences (CARES).

“Early this fall, a schoolteacher friend called me and told me that the anxiety she experienced was so significant that many days this fall, she felt like quitting,” said Haynes.

Similar reports from other schoolteachers — angst over not knowing district plans, concern that students wouldn’t adhere to mitigation strategies like masks and sanitizer — convinced Haynes that the negative impacts of the pandemic on school staff might outlast the crisis itself.

She enlisted Heather Bush, PhD, an endowed professor of biostatistics in the UK College of Public Health and endowed professor in the Center for Research on Violence Against Women, as well as others, including Kate Leger, PhD, assistant professor in psychology, to assist in developing and administering a survey to gauge how the pandemic is affecting school staff.

A schoolteacher friend of Haynes’ helped the research team build a fortuitous connection with the president of the Ohio Education Association, who was very supportive of their project and even connected them with the education association presidents in Kentucky and Indiana.

“As president of the Kentucky Education Association, I have personally talked and emailed with many members about their daily experiences in their schools," said Eddie Campbell. "I know first-hand that our educators are overworked, stressed, and exhausted. During many of these conversations, educators have told me that they are ready to leave the profession either by resignation or retirement. Stress is a very significant issue. As we prepare for the Spring semester, we know that our school’s teaching modalities will change multiple times, and our school staff will be required to continually change their practices to keep ourselves, our co-workers, and our students safe.”

The research team organized a School Staff Advisory Board consisting of union leadership, teachers and other school staff from all three states to inform the research plan. The board influenced the development of the survey’s questions and how and when it’s administered; they will also be instrumental in determining the best ways to share the study’s findings with school staff and leadership.

Together, the research team and School Staff Advisory Board envision this study not as a brief investigation but as an opportunity to look at the long-term health and psychological impacts of the pandemic on school staff.

Based on the survey data the team has collected to date, teachers who taught both online and in-person reported more symptoms of anxiety and depression and lower levels of positive psychological wellbeing than teachers who either strictly taught in person or online, but not both. These findings highlight the toll of shifting and increasing job demands on the mental health and wellbeing of teachers.

Haynes also noted that teachers are being asked to sanitize their classroom between each class and often aren’t properly trained on how to use these chemicals or given the proper protective wear, such as gloves, to use them.

Though the survey has mainly been distributed through the Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana union listservs, the immediate flood of nearly 10,000 survey responses, well beyond typical survey response rates, demonstrates that school staff have a pent-up need for a voice.

“This survey provided a confidential forum for school staff to be able to say ‘This is what’s happening to me,’ and I don’t think they have anywhere else to voice it,” Bush said. “For a survey that just was sent via email, I would have expected maybe a couple of responses. So after two or three days when we hit 7,000, we were shocked – this kind of immediate response to a survey is not like any other we have launched.”

Bush and Haynes predict that since the effects of COVID-19 on school staff — whether through trauma, burnout, or exposure to environmental factors—will be long-term, the study’s findings could have major policy implications.

“Our ultimate goal is to be able to inform school decision-makers of what mitigation strategies worked to slow the spread of the COVID-19, from online teaching to wearing masks, adjusting hallway flow, use of disinfectants, and other strategies. We are also measuring the unintended consequences these strategies have had on mental and physical health of school staff,” said Haynes.

The pair has already applied for a grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue the study and follow this school staff cohort over the next several years. They’ve also teamed with the colleagues in UK’s Gatton College of Business and Economics and the College of Pharmacy to examine the ability of multilevel interventions within K-12 schools to mitigate and reduce the spread of COVID-19 within school districts, including students, staff, and communities.

The survey is still open for school staff to share their experiences at https://bit.ly/WellSchool.

This research is currently supported by internal funding, with support through Haynes’ and Bush’s leadership roles in the UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UK CCTS) and the UK Center for Appalachian Research in Environmental Sciences (UK CARES).