UK HealthCare providers advocate for patient care in Washington, Frankfort

LEXINGTON, Ky. (April 30, 2024) – They say there are two things you never want to see made – laws and sausages.

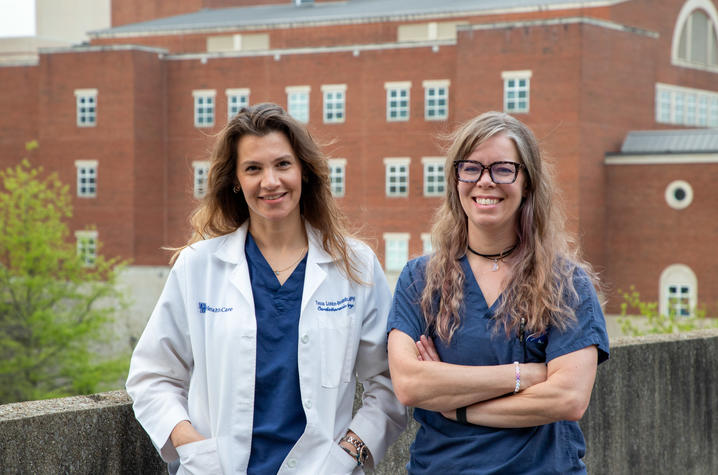

But that was not the experience of UK HealthCare cardiovascular surgeon Tessa London-Bounds, M.D., and registered nurse Amanda Crabtree. When they went to Washington to advocate for access to medical technology for their patients, they met with members of Congress and their staff on behalf of thousands of Kentuckians.

Representing the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, London-Bounds and Crabtree were on a delicate mission: to make in-home INR testing available for patients on Medicaid.

On paper, their request looks like any other proposed legislation, with estimated costs, outlined benefits wrapped in bureaucratic language. But the impact would be real and affect not just their patients, but more than 3,000 Kentuckians.

“It’s shown how important for us as clinicians and health care workers to be a voice for our patients and communicate in a way that our legislators will understand,” said London-Bounds. “It’s been really wonderful for us to be able to advocate for our patients on a national level.”

INR stands for international normalized ratio; it is a measurement of the coagulation properties of blood. For patients who take blood thinners, the INR determines the dosage of their medication. Not enough could cause a blood clot, which in turn could lead to a stroke. Too much blood thinner comes with the risk of bleeding out from a wound or incision. Blood thinner medication is also reactive to diet; leafy greens, other medications and certain juices and alcohol can all affect the drug’s effectiveness.

With so many factors contributing to such high risks, it’s easy to see why an accurate INR reading is important. And thanks to the efforts of London-Bounds and Crabtree, patients on Medicaid can do their own INR testing at home.

One subset of affected patients is those with a history of intravenous drug use that led to an infection of the heart valve. Called endocarditis, the disease necessitates the replacement of the heart valve, either with a mechanical valve or a biologic valve from a cow or pig. Mechanical heart valves require patients to take a blood thinner for the rest of their lives, but are very durable and can last for 30-40 years. Biologic valves do not require blood thinners but the valves only last 5-10 years, sometimes less in younger patients. When the biologic valves fail the patient usually requires another operation.

Surgery for endocarditis is complicated, with a litany of post-operative requirements. One part of the follow-up is that patients with mechanical valves must have their INR tested weekly to ensure the correct dosage of their medication. Not being able to test at home is one more obstacle in their road to recovery.

“Ideally, we would offer more patients mechanical valves,” Sami El-Dalati, M.D., infectious disease physician and director of UK’s multidisciplinary endocarditis team. “But depending on the patient’s living situation or availability of transportation, having labs drawn once a week is too much to ask. The ability to accurately follow INRs was affecting our ability to offer patients their best treatment option, a mechanical valve. We knew that patients on Medicare were eligible for home testing kits but further investigation revealed that Kentucky Medicaid didn’t cover them. We set out to see if we could change that.”

Weekly testing means weekly trips to the hospital; patients have to take time off work, arrange for childcare and find transportation. For patients from rural areas of Kentucky who come to Lexington, this otherwise quick blood test can take the entire day. INR tests in the clinical setting are venous blood draws; Those with a history of intravenous drug use have both physical and emotional trauma when it comes to needles.

“Oftentimes, if people have a long history of IV drug abuse, not very many superficial veins can be accessed, so those patients will be stuck 10, 15, 20 times and be bruised up and down their arms because their blood is so thin,” said London-Bounds. “It’s a very taxing experience for them.”

“One of the other hesitancies about coming to the hospital is a lot of people with a history of substance abuse are very wary of health care providers in general,” said Crabtree. “They feel like their being looked down on because of their history. And one of the most important factors in their recovery is having a good relationship with their providers.”

“Testing at home would be life-changing for those patients who have put forth a lot of effort in their recovery,” said London-Bounds. “It takes a lot of the difficulty out of an already-difficult situation.”

An at-home INR test is a quick finger stick, similar to the glucose monitors used by people with diabetes. From there, an instant reading informs a medication change. Before, patients would have to wait a days for results from the hospital lab.

Armed with data, cost-benefit analyses and other metrics that appeal to lawmakers, Crabtree started reaching out to state legislators in June of 2023, asking for their help to expand Medicaid coverage for the testing kits. She was warned that the process could take years; new legislation is subject to debates, changes and votes before it comes to the Kentucky House floor. But with unprecedented expeditiousness, House Bill 31, introduced by Representative Deanna Frazier Gordon of Richmond, flew through both chambers with unanimous approval from both parties. It was signed into law by Gov. Andy Beshear on April 4, 2024, just four months after being introduced to the House committee.

“A lobbyist friend of mine said it was like lightning in a bottle,” said Crabtree. “He had never of anything moving so fast before, even though it seemed slow to me.”

Joshua Gilvin is one of the patients who would benefit from London-Bounds’s and Crabtree’s work. Diagnosed with endocarditis in 2016 after years of struggling with substance abuse, he underwent a valve replacement and is now three years into his recovery journey. His INR is tested weekly, which means an hour-long drive into Lexington for routine blood work.

“I have nowhere to get it pulled from,” said Gilvin, whose veins are compromised from years of intravenous drug use. “They said they had these stick finger tests that if we could get it together that we might be able to get them. I’d love to be able to do that, be able to go home, check it myself and adjust my medicine. Then I can call back and say, ‘Hey, this is what the level is, what should I do?’ Some people might do that and some people might not, but I would. If you care about yourself, you’re going to do it. I’m trying to get better so I would.”

The multidisciplinary endocarditis team at UK HealthCare work with patients like Gilvin to ensure he has the resources he needs as he navigates his recovery journey. At-home INR testing kits are a major part of giving patients independence and autonomy, as well trust that they can take care of themselves and be successful as they heal. Other patients on Medicaid with common but serious heart conditions such as atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and other blood clotting issues will now have access to home testing kits.

London-Bounds and Crabtree have their sights set on a nationwide change, expanding access to INR kits to states with a similar Medicaid population, as well as states that don’t have the same health disparities as Kentucky. They met with Kentucky Representative Andy Barr and the staff of Senator Mitch McConnell to discuss the idea of expanding home-testing access. Bolstered by their success in Kentucky, London-Bounds and Crabtree feel optimistic about the impact health care providers can have in politics.

“It highlights how important it is for providers to be advocates for their patients, because even though lawmakers mean well, they may be disconnected from the issues our patients are dealing with,” said London-Bounds. “It’s been wonderful to be able to advocate for our patients on a national level.”

Crabtree agrees, and is proud of the fact that this change begins at UK.

“UK is really good about being supportive in all aspects of people’s care, and giving them second chances,” said Crabtree. “We now have an audience with the people who can really make a difference.”

UK HealthCare is the hospitals and clinics of the University of Kentucky. But it is so much more. It is more than 10,000 dedicated health care professionals committed to providing advanced subspecialty care for the most critically injured and ill patients from the Commonwealth and beyond. It also is the home of the state’s only National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, a Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit that cares for the tiniest and sickest newborns and the region’s only Level 1 trauma center.

As an academic research institution, we are continuously pursuing the next generation of cures, treatments, protocols and policies. Our discoveries have the potential to change what’s medically possible within our lifetimes. Our educators and thought leaders are transforming the health care landscape as our six health professions colleges teach the next generation of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other health care professionals, spreading the highest standards of care. UK HealthCare is the power of advanced medicine committed to creating a healthier Kentucky, now and for generations to come.