How UK Alum Loren Long Painted His Own Way to Success

LEXINGTON, Ky. (July 29, 2019) — Madonna. Sports Illustrated. Wall Street Journal. HBO. Time. President Barack Obama. Only a chosen few can ever say they worked with such a list of industry leaders and icons as part of their craft. But these are just some of the former clients of University of Kentucky art studio alumnus and New York Times bestselling children's book illustrator and author Loren Long.

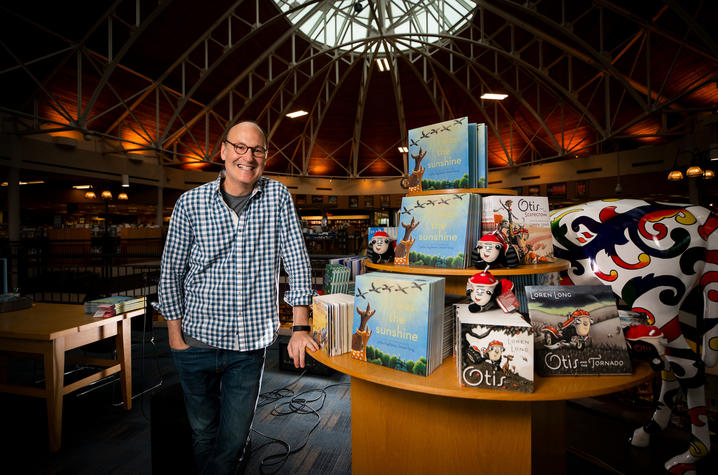

Earlier this summer, the celebrated illustrator traveled back to his hometown of Lexington on a tour for his most recent book, "If I Was the Sunshine," written by Julie Fogliano.

In addition to illustrating many of the most noted children's book projects of the last two decades, families are likely familiar with Long's work as creator of the popular "Otis" series, a character inspired by a tractor on a Lexington horse farm where the author worked during college.

UKNow caught up with Long at his last stop on his most recent book tour at Lexington's Joseph-Beth Booksellers. The artist talked with us about his success and how one UK professor helped him realize his calling.

UKNow: You're from Lexington. Tell us what it was like growing up in the area.

Loren Long: Well I grew up in Lexington. I was born in Missouri, but we moved here when I was 6. I went to Clays Mill Elementary, Jessie Clark Junior High School and Lafayette High School.

And, it was great, a very typical childhood. My parents were not artists. My dad was a traveling sales rep for a building supply company, mom was a secretary at a variety of different businesses. I didn't grow up in an artistic sort of family. Athough my mom had a flair for decoration and designing, and she encouraged me.

I started drawing at a very early age, but I had no idea that I would have a career in that. It was a very wonderful childhood in Lexington. The only art training I had was nothing outside of the house, nothing outside of school. Very little, really, in elementary school back then. But I got to Jesse Clark Junior High School and my two favorite classes — I'm not proud to say — were PE class and art.

And so, all my electives were filled up. All three years of junior high school — art, drawing, painting, ceramics, all of that. I took everything they offered. And I was very fortunate at a fairly formative age to have an art teacher by the name of Mr. Pennington. I believe his name was Ron Pennington. He was also a football coach.

He just was very kind, and he started showing my art in front of the class. And for a little kid who was the furthest from a football player, for the football coach, who was also the art teacher, to show my art in front of the kids saying, "this is what Loren did for the assignment," it was a tremendous boost to my sort of psyche and who I thought I was. I'll never, ever be able to repay him for what he did.

Then in high school, I was fortunate enough to have Ms. Clifton (one of two art teachers at Lafayette). And, she started bringing her art books from home — her own books. She saw the interest that I had in art. And I was not a great student. But she saw that interest in me and started bringing books from home to introduce me to famous artists like Vincent van Gogh. And she really did, she brought this big, thick, Norman Rockwell book. Boom. "Come here, Loren, let me show you."

I think about that. All these people that give themselves to other people in the education field. And they don't have to do that. They can just teach. But she took extra time because she knew I was interested, and she saw something in me, I guess.

UKNow: And at UK?

Long: Then at the University of Kentucky there was a graphic design instructor by the name of Jim Foose. And I took all of his classes. He started calling me the illustrator of the class in his graphic design class. And that unlocked something in me. I mean, I really owe those three educators with nudging me along. And Mr. Foose, in a way, telling me what he thought I was.

I respected him. He was a talented watercolor painter. And when Mr. Foose started calling me something, I listened. And then he not only told me what I was, he showed me. He started bringing his illustration annuals. Because I'm like, "What is an Illustrator? What do you really mean by that? I've heard of Norman Rockwell and all that, but I don't have any references in my life." He was explaining to me why he said I was an illustrator, because I was always turning in a painting or a drawing when everybody else was turning in a text, or a typeface, and color, and photographs. He said, you're an Illustrator. Every assignment you do a drawing or painting.

And then, he took a group of students to a graphic design symposium in Marshall, in West Virginia. I sat in that audience because of Mr. Foose. I would never have been there if wasn't for him. I saw two illustrators speak that were contemporary working in the field today, by the name of Gary Kelly and Mark English. Big giants in the world of freelance, broad-based illustration. Not picture book illustrators, which I ended up being, but I sat there as a kid, probably 20 years old, I guess 22, and I said, "That's what I want to be."

Then the rest of it is just setting about working toward achieving it.

UKNow: Tell us a little bit about your practice. What does a day look like for an illustrator?

Long: Well, everything's different. I'm not a big early riser, so I start my day off with reading the newspaper. I still kind of like that as a ritual. And I try to get to my studio (at his Cincinnati home) around 9 in the morning.

When I'm on a book deadline, when I'm in the final paintings of a book, I'll spend 10, 11 hours straight painting with breaks.

I try and work like I'm a laborer, like a tradesperson. In other words, it's the work that matters. You cannot finish a book; you can't write a story without focusing.

UKNow: Tell us about your first break on a project.

Long: So, I graduated from the University of Kentucky. I wasn't quite ready. I went to art school for one year. The Art Institute of Chicago didn't let me in because I was a graduate and I would have been an MFA. I was a representational artist, and they were looking for more abstract expression artwork — which I love, by the way — and did a little bit of at UK. But I got into the American Academy of Art in Chicago.

As a freelance illustrator right out of school, I started while I was working at Gibson (a greeting card company). At night, I would go home and do magazine illustrations, editorial illustrations. And one of my first big breaks was a call from Time magazine. And I illustrated for Time magazine maybe a dozen projects over the course of five years.

And, I started getting into the juried exhibits in New York, like the Society of Illustrators and the Communication Arts Magazine, and Print, which is a design publication. So, they're trade publications — and art directors started seeing that.

Then I started getting calls from Time, Sports Illustrated, Atlantic Monthly, Wall Street Journal, Reader's Digest — and I thought I'd arrived. So maybe the first 10 years out (of school). I was rolling. Time magazine could call anybody on the globe, and they were calling me in the Cincinnati area to do a portrait of Bob Dole when he ran against Clinton for president. They called me. I let Thomas Hart Benton and the American Regionalist painters — the WPA muralists — sort of seep into my work, into my style and the way I was painting and drawing. And, the magazines picked up on that.

Time had me do a picture of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, a portrait of him sitting in his jail cell. They were illustrations. And then I did Terry Nichols, who was his accomplice.

So, these people in New York started looking at me as this middle-American painter, and I was the only one in the illustration field in the '90s — one of a few — that was doing this American Regionalist look. Sports Illustrated had me do a lot of period pieces. I painted the famous Walter Hagan, the golfer from the early 1900s. Sports Illustrated had me do that because of the style, and that early 1900s feel in my work. So, it was wonderful.

Publishers started seeing my magazine work in New York, and then they started calling me to do book covers. So, I started doing book covers — and a lot of them were young adult novels, YA. Eventually, other publishers saw my covers and one called me to do a picture book.

About that time, Madonna — the singer, the rock star singer, the Material Girl, Madonna — wrote a handful of picture books. It was right about the time when she had her daughter and she wrote a story called "Mr. Peabody's Apples," and of all things she chose me.

It's not like Madonna knew who Loren Long was, but the publisher shared my work with her. She chose me because of that American Regionalist feel. And that was a big break, not because the Madonna book changed my life because it was this famous woman. But because she was a famous woman, every publisher on the planet knew all of a sudden who Loren Long was.

She, he, they didn't know who I was, where I was, what I was, but they knew my name. And it made Penguin, who I just signed a book deal with, stand up and kind of pay a little more attention to me. This is my version of the story. And so, I was kind of off to the races. I got there a little quicker with some entry into the children's picture book illustration world, which, by the way, after about 16 years of it now, I can tell you is the greatest place in my mind — and viable — to make art for a living, to make pictures.

It's storytelling. Really, it's this beautiful art form. It's all for children. So, I came to a time in my life where my work pretty much is dedicated to children. And I can think of a lot of worse places to dedicate one's life's work

UKNow: Tell us a little bit about "Otis."

Long: People ask me a lot, because I guess I've done around 20, or 23, or so books, which one is most special to me. And I'm very proud of every book I've done from the very beginning to now. I put the same amount of effort, and time, and drive into each one. But probably my book that I'm most proud of is "Otis" — "Otis the Tractor." Because I both wrote and illustrated "Otis."

I've illustrated more of other people's books than I have my own. And I may keep doing that. But I love the challenge of writing. I had this great sort of blessing in my life, really, of "Otis the Tractor." And it's coming up in 2019 on its 10-year anniversary. In that book, the new anniversary edition of the original "Otis," there are going to be sketches and notes in the back of the book printed in there of what it was like to make up the character, and some of my thinking, and a little letter in the front.

I'm proud of those because it was my creation. And it kind of came about organically. It was a story that my wife sort of made up, and it was a friendship between a tractor and a little calf. The calf gets in trouble and the tractor saves the calf. Their story was called "Little Green Samuel," and it was a story about the tractor and the friendship was the farmer's son. They never wrote it down. This is my wife telling it to my two sons back in the day, just driving around, taking them to school, dropping them off here and there. They would talk, and just like humans do, we share stories, we make up stories.

But I had already had this experience working on a Lexington horse farm that was called Walnut Hall Stud Farm out on Newtown Pike. And it was my job for a couple of summers during my college life at the University of Kentucky. We weed-eated and mowed in the morning, and in the afternoon, toward the end of the summer, we baled hay. It was a great experience, very hard work.

There was a little tractor we all got to take turns driving. And it was a Ford. So, the front end of it inspired Otis. I made the decision to make him have a single wheel on the front as opposed to the two wheels, and I named Otis after my favorite character from "The Andy Griffith Show" — Otis Campbell. I just thought it was such a great name for a hard-working character — loves his country, loves to work hard and play hard. I just thought Otis the Tractor just had a ring to it.

UKNow: In recent years you acknowledged that you are color blind. Can you tell us a little bit about how you overcame that and how you kept your dream going in a visual art field?

Long: I never talked about it until like two years ago for two reasons — I worried that somebody wouldn't hire me, and then the other part was I didn't want to bring attention to me. How could I complain about being colorblind when somebody else is blind? So many people overcome bigger obstacles than this. It's not by any stretch some kind of tragedy or crisis. It's just a very annoying inconvenience. And it is an obstacle.

Basically, the bottom line is I cannot see the difference in brown and green, and blue and purple. Dark purple and navy blue are the same to me. I can't tell you which color is which. Most browns and greens, same way, and light blue and lavender, same way.

But just like a person who's illiterate and becomes a CEO of a company because they use other parts of their brain and they're smart enough to figure it out and fool the world in a way, that's kind of how I was with colors. I could have a UPS driver at my front door help me with color and he doesn't even realize it, if Tracy, my wife, isn't there.

So, my mother helped me. We discovered it when I was just getting normal glasses, and all of a sudden it started making sense. Yeah. Wait, are the Kentucky Wildcats purple or blue? Well, they're blue because I live here and they say, "Go Big Blue." But it looks purple to me.

The way I deal with it is, I get people to help me check my work. When nobody's around, I just start with the colors in the same spot on my palette. I put the blues as far away from the purples as I can, I put the browns as far away from the greens as I can, and then I write on the palette, blue, purple, and then I label black, because when wet paint is on a palette it looks darker in some cases. That's kind of how I get around it. Then I have my wife and my two sons, and before I left for college it was my mom that helped me.

I haven't done a painting in 26 years, really, for any of my books that Tracy hasn't seen, or one of my boys hadn't seen. So, they could say, "Hey, you might want to watch that green horse. Or those leaves got really brown. Did you mean for them to be brown?"

And then sometimes if there's an effect — I can see a beautiful sunset — I just can't tell you what all the colors are. I can see how it's intense and gorgeous. Sometimes I'll take a photo of it, or I'll just get a notepad out and have Tracy tell me what all the colors are. She'll say, "Yeah, there's a little pink underneath that cloud, and the cloud has a purple haze on the under ridge." So, I just take notes.

UKNow: Do you think it's impacted your choices?

Long: I always feel like it's been a little negative because it's such a struggle. I can't paint like a real portrait painter. I can't paint like John Singer Sargent, because he could see these subtle hues, he could see all those variations in our flesh tones. We have green, we have browns, we have pinks, we have purples, we have oranges. There could be a yellow bus going by and it reflects yellow on the side of your face.

And I know all this stuff intellectually and scientifically. Like, I know color theory. What it has probably done for my work is kept it, in a way, kind of simple. And my light sources are very important to me, and value structures.

It's like if you're a blind person, your sense of hearing is acute. So, since I can't see the hue, which is the color, the sense of value is acute. I'm always very concerned about a nice structure of value — lights and darks, mid-tones. The way I achieve that is usually one light source. I always kind of know where the light source is on my art. And then I tend to try and have heavy shadows.

I do think it has affected it, in some ways positive and other ways negative.

UKNow: You still do your work by hand. With digital resources on the rise, will you be working in digital at some point?

Long: Moving forward, the picture book world is going to be more and more increasingly digital. A lot of artists are scanning in their drawings, and even paintings. And then they're going into Photoshop and different programs and making really wonderful layered art. They can do effects with the computer that I can't do by hand.

I don't do my art on a computer at all now. But I probably will at some point, because I just think it's another medium. It's just like the difference in acrylic paint and pastels, or watercolor and gouache. I really admire some of the work that's being done. It's just that right now I love doing it the old-fashioned way — the way I did it when I was little.

I like working with my hands, getting my hands dirty. And I like the human error that just keeps happening on every painting and every book. I want people to feel my art, and I want them to see how it's hand-created and not perfect.

UKNow: Is there anything you'd tell a student that maybe wants to follow in your footsteps and illustrate books?

Long: Yeah, I would say, become a student of this field. And it's not hard. Let's just say you wanted to be a guitar player. You would probably study and listen to Eric Clapton. You might study and listen to classical guitarists. You might pay attention to Jimi Hendrix.

Same thing with this field. You want to be a picture book illustrator? You ought to be able to name off a dozen of your favorite, living, contemporary illustrators, whether it's me or the next person. My advice is to become a student of the work that is going on now in our field, and before us. Ask your parents what their favorite books were when they were kids. Look up the work of Virginia Lee Burton and all the artists that came before us in this field. It can only help you decide who you're going to be in the field.

The way to do it is become the Joseph-Beth. Talk to the booksellers in the children's department, go to your branch library and talk to the children's book librarians. Who are their favorite artists? Then you can start following all those favorite artists on social media. You don't have to even do social media, but you can follow them, and you can see what books they publish. Look those books up. Get to know them. Let them inspire you. Let some of the best of their stuff seep into your stuff.

And then even more fundamentally, later you can see who their agents are, their literary agents, and who their publishers are and who their editors are. And then you approach them, you approach their agent. That's one way to do it.

UKNow: What projects are you working on now?

Long: "If I Was the Sunshine" is my brand-new book (published in May 2019). It's written by Julie Fogliano, who is an Illustrator that lives up East, in the New York area. These days I work with an agent, and he shared this text with me. And I just thought it was this beautiful poem of perspectives and relationships among people, but also among animals and in the big world of nature. I gravitated toward the poetic rhyming. It's "If I was the sunshine and you were the day, you'd call me hello and I'd call you stay."

It was a little bit hard to illustrate because it's not literal. You can illustrate sunshine. You paint a sun. Maybe you've got a smile on it. But how do you illustrate day? The term — day. How do you illustrate stay? It was a real thinking kind of illustration assignment. And that kind of also challenged me, and I just thought it was a great thing for my career at the moment.

I'm always working on two or three books. So that one's done. But when I get home, I'll be working on a Christmas title that I can't really talk about yet, that'll come out in like 2020. And then I've already accepted a project for 2021.

We work a year in advance. So, I always have a book or two in the works, and I'm trying to write as I go. I illustrate other people's stories, write my own a little bit, and out of those, do a little traveling, visit three or four schools a year and if you're toured, visit a bunch of schools in two weeks. It's a great life. I love it.

UKNow: And what inspires your work — travel, working with kids, a specific artist?

Long: What inspires me is almost all of the above. So sure, travel, but really, the older I get, sometimes it's themes. What do I want to say? What do I want to say if this is my last book? If I'm going to die, what do I want to say to the world?

And, it's not didactic. It's not. We don't want to preach with children's books. Those are the worst books, right? It's great if you can entertain and have something of meaning. Like my book, "Little Tree." The reason I came up with that is because my oldest son was preparing to leave for college, and I was having a really difficult time, just emotionally, with the idea that, am I done? Is that it? I didn't finish everything. I'm not sure I did my job perfectly.

I felt like a little tree who was afraid to let go of its leaves. And then I asked myself as a creator, as a writer, what would it be like? What would happen if I was a tree that didn't let go of its leaves? Well, they'd turn around and brown and gray, and while everybody else dropped their leaves, he would hold on to his and be comfortable. But then the next spring, all the other trees would bloom and these beautiful, green bursts of life — their leaves would be beautiful. And the little tree would be fine because he still has his leaves and he's comfortable, but he'd look over and they would be a little bit taller.

So, when you hold onto something like that it can just stunt your growth. That was the theme of that. And, that was probably my most personal book, and one of the books I'm very proud of. Then some of it's just simple, some of it's commercial.

And, I'm interested in inclusiveness — and not just racial diversity, but socioeconomic diversity, and religious diversity. Things of that nature are things that mean a lot to me. I'm not sure if it's a responsibility, but it is something I care about. It's not a political thing. It's a human thing. It's a do the right thing thing, in my mind. And with children's literature you can do that. You really can.

To find more out about Long and his work, follow him on social media on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

The UK School of Art and Visual Studies, part of the College of Fine Arts, is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design and offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in the fields of art studio, art history and visual studies, art education, curatorial studies and digital media design.