Grad From Lee County Researches Appalachian Stereotypes

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 5, 2017) — When Chelsea Adams graduated from the University of Kentucky, she had18 guests come to the ceremony — her parents, cousins, aunts, uncles, and people she describes as family, but who aren’t “blood-related.” While the event brought them together, the bachelor’s degree marked a distance between Adams’ present life and the one she left behind in Lee County.

Less than 6 percent of adults in her hometown have a bachelor’s degree — the lowest rate in the state. It’s not that schools in Lee County aren’t preparing students well. The college and career readiness statistics are near levels elsewhere in the state. In fact, many of Adams’ classmates went to college or trade schools. Jobs back home are limited, though, so many of them don’t return. In fact, more than a third of people in the county are living in poverty.

Adams’ parents stayed in Lee County, and have done well. Her mother was valedictorian in high school, but was already married when she made her speech. She works in an administrative support position for Lee County Schools. Her father had been working in the oil fields since age 16 and, rather than college, they just wanted to settle down together as newlyweds after high school.

Adams followed in her mother’s footsteps of academic success. Her high school class was competitive, and she finished in the top five and was selected as a Governor’s Scholar. She was poised to become a first-generation college student and started telling people she wanted to attend the University of Kentucky.

“I don’t know,” teachers and important people in her life would say to her. “It’s a big school....” Although they were not trying to be hurtful, their words still cut through Adams' dreams like razors.

“Everyone fantasizes about UK in Eastern Kentucky,” Adams said. “People truly bleed blue. It’s drilled into you from a young age. I have photos of myself as a 4-year-old wearing a UK cheerleader outfit. At one point, we had season tickets to basketball games. My brother and I would fight for who got to go with Dad. You’re kind of bred into it, but it didn’t have anything to do with the academic side of it.”

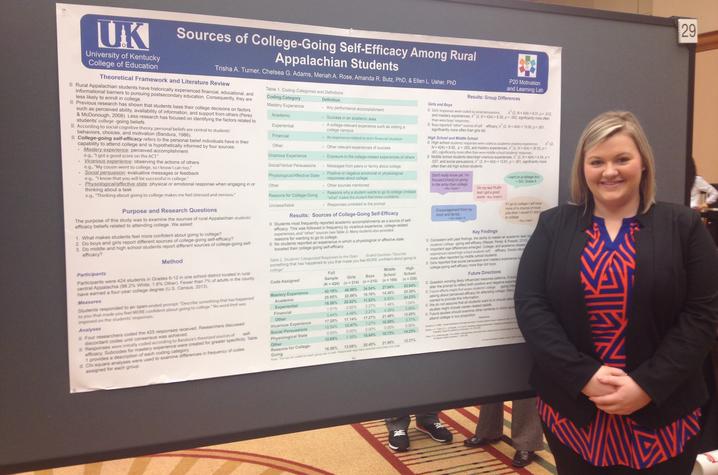

Adams will be in Rupp Arena once again this weekend, walking across UK’s Commencement stage, this time receiving her master’s degree. Her master’s thesis is titled, “I Wonder What You Think of Me: Stereotype Awareness in the Appalachian Student.”

You’re Only Limited By Your Own Expectations

Adams had never heard of educational psychology. But she needed course credit and an email came through from a researcher at the UK College of Education. Ellen Usher was inviting undergraduates to be part of the research team in her Motivation and Learning Lab.

“Having that placed in front of me was kind of like fate,” Adams said.

Usher’s work looks at what motivates students to do well in school. This includes examining how distinct cultural values might relate to students’ motivation. Ever since her first day on campus, Adams had come to see herself as being from a different culture. It started the first time she spoke during orientation.

“Oh my gosh,” another student exclaimed. “Please keep talking. I love that accent.”

Adams shut down and withdrew from the conversation. She describes the experience as difficult, but says she eventually met people more like herself and began to come out of her shell.

Still haunted by cautions people had made to her about going to college on a large campus, she found solace through her work in Usher’s Motivation and Learning Lab. There, Adams began drawing connections between theories discussed in the lab and her lived experience back home, where cultural values seemed especially influential on people’s life choices.

She questioned how she had defied the odds to attend her dream school, when others who were just as capable had not.

“In the lab we study self-efficacy, which refers to beliefs in one’s own capabilities. This basically means that, whether you think you can or you can’t, you’re right,” Adams said. “Growing up, my mom always said, ‘You’re only limited by your own expectations.’”

It was by leaving home that Adams began to truly to understand that statement. And as her understanding of the psychological aspects of education grew, Adams was learning that maybe she could play a role in doing something to pave a smoother path for a new generation of students.

An Awakening

She often felt like an outsider no matter where she went.

“When I would go home, people would say ‘you’ve lost your accent,’ or ‘you think you’re big and bad now that you live in Lexington,’ and then I would return to Lexington and feel like people were thinking badly of me because I still had that country accent,” Adams said.

She admits college did change her, almost instantly. She was making up for lost time, soaking up the multicultural experiences that weren't available in her earlier life.

Adams recalls going back to her freshman dorm room and crying after a multicultural psychology class one day. It was dawning on her just how much her limited experience of being around people from different backgrounds influenced how she viewed others. After all, she didn’t want to be stigmatized for being from Appalachia. But was that fair, she wondered? She too was learning about her own stereotypes about people from other cultures.

I Wonder What You Think of Me

Adams’ personal awakening led to her research focus in Usher’s lab.

“My goal was to understand students’ perceptions of stereotypes and whether they think of themselves as others think of them,” Adams said.

For instance, someone who anticipates people in his life will discredit his intelligence based on where he is from, how his accent sounds, or his income level will likely start to feel he isn’t smart or capable based on the same faulty line of reasoning.

It’s called stigma consciousness and Adams theorizes that ending the cycle could have quite an impact.

“We talk about educational attainment gaps for race and ethnicity and differences in sexual orientation and gender, but we rarely look at the cultural context in Appalachia and the way that plays into educational attainment, motivation and self-efficacy,” she said. “Seeing that gap made me want to bring it all home.”

Usher recalls how Adams’ enthusiasm and curiosity as an undergraduate at UK shifted the focus of the members of her research lab.

“Chelsea opened us to the Appalachian experience,” Usher said. “Because of her influence, more than 20 members of my research team have been involved in looking at academic motivation in rural Appalachian students and teachers for the past four years. Some people think that UK students work in labs to support faculty members’ research agendas. The opposite is true here. Chelsea has fundamentally changed my research and has opened doors for fellow undergraduate and graduate students to examine educational psychology in rural Appalachia.”

For several years, Usher’s team traveled east to conduct surveys and interviews among elementary, middle, and high school students. One question asked students to describe what they think people from their community expect them to do after high school.

“For those who were struggling academically, they assumed people expect them to possibly get a job after high school,” Adams said. “But they also contended people expected them to be a bum, to draw a check.”

Adams doesn’t think schools are doing justice for those students.

“Just a few words from only a couple teachers really impacted me,” she said. “But if students are hearing no encouragement and assuming there are low expectations for them from all angles in their lives, then there’s no wonder there’s such an education gap between rural Appalachian students and those in other settings.”

Making a Difference

Often, a challenge for researchers is in finding ways to apply what they have learned. Adams reflects on how she can use her own experience and research to create transformative moments for students like herself.

“My main goal is to bring awareness to words,” she said. “I remember growing up we had ‘I can’ statements written on the board. I want to see messages going to students like ‘I can think about going to college,’ or ‘I can study for the ACT.’ Getting back home and letting students know they can do those things is really important to me.”

She will work for the Upward Bound program this summer, mentoring high school students from low-income families or families in which neither parent holds a bachelor's degree. She hopes to influence them in ways similar to how she has been able to influence students while substitute teaching in Lee County.

“Students tell me, ‘I’ve seen you go to UK to succeed’ or ‘I see that you are in graduate school; that’s so inspiring.’ It’s heartwarming to know it is being noticed. Being from a rural area instilled in me this idea of working for the betterment of everybody and not just myself. Everyone is connected in my community. When one person is sick, the whole community will rally to provide food, money and rides to doctor appointments.”

Adams doesn’t think she will be able to find a job in her hometown, but hopes to find other ways to give back to her community and Appalachia in general.

“Having left, I don’t want to be on the outside of the closeness and support of my hometown. So, I am driven to use what I’ve learned at UK to contribute to the betterment of the community. That’s why I became a researcher and it’s a researcher’s job to figure out what’s not working well in a situation and what can be done to fix it. I am not claiming to be a savior of my community. I just want to do my part for a place that did so much for me.”