UK Faculty Member, Alumna Expand Access for Students Who Are Blind

LEXINGTON, Ky. (April 13, 2021) — For Sydney Clark, every day presents challenges. She was born with a genetic condition that resulted in vision loss over time.

By the time she was a teenager, she was almost completely blind.

“Accessibility is always an issue,” Clark said. “I've never had an experience where accessibility wasn't an issue."

But Clark never allowed her disability to stop her from achieving her goals. And one of those goals was to attend the University of Kentucky.

The transition from high school to college can be challenging for any new student, but when Clark came to UK as a freshman in 2014, the Frankfort, Kentucky, native found herself facing more challenges than she was used to.

“I started reading Braille in class from the time I was five, all the way through high school,” Clark said. “But when I came to college, I didn’t always have a worksheet or something in front of me to read. That was a hard adjustment for me.”

Clark decided to major in public health, which required her to take nine science courses. However, many instructors were unaware of the resources and considerations needed for students who are blind.

“We live in an ableist society — it's just not designed for people like us,” Clark said.

While Clark was used to educating others about her disability and communicating what she needed to succeed, she admits it was a lot of pressure for a full-time college freshman.

Fortunately, Clark had a wonderful support system in the UK College of Public Health. Her advisor, Marilyn Underwood (now retired), along with faculty mentors Nancy Johnson and Anna Hoover, helped Clark navigate her way through a variety of biology, anatomy and other science courses.

“They really did everything they could to help me succeed,” Clark said. “They're some of the best people that I've ever met.”

One of her anatomy instructors, April Hatcher, went the extra mile to help her.

“She’d meet with me twice a week, outside of class, to make sure I was grasping the material,” Clark said. “And that was the first experience I had with someone who really put forth a lot of effort to make sure I could succeed.”

According to Clark, an instructor’s level of effort in making their course accessible is what truly made a difference in terms of her success.

By her senior year, Clark was just one course shy on her science requirements, and she was running out of options. That’s when her mentors told her they found a faculty member in the UK College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (EES) who had expressed an interest in helping.

As a public health major, Clark hadn’t considered taking a geology course, but decided to enroll.

Kent Ratajeski, senior lecturer in EES, had been teaching geology for nearly 20 years, but had never taught a student who was blind before. After meeting Clark in 2017, he immediately became aware of the accessibility challenges she and other students who are blind experience in the classroom.

With a research interest in geoscience education, Ratajeski knew he needed to think differently about how Clark would experience and understand the course content.

“Open any geology textbook and you will see full-color graphics — photographs, illustrations, graphs and maps — on almost every page,” Ratajeski said. “Accessible textbooks exist, but they only go so far in explaining pictures and diagrams in words. I wanted Sydney to experience the rich visual world of geology in a more direct and unfiltered way.”

That semester ended up becoming a significant learning experience for not only Clark, but for Ratajeski as well.

To help her understand diagrams, graphs and maps that most students can see with their eyes, Ratajeski worked to convert his course materials into formats Clark could use. He spent many hours in his basement creating tactile graphics out of clay, Styrofoam, fabric and wax sticks.

“He was super dedicated — he would go to Hobby Lobby to make things like clay volcanoes, and different stuff for the labs,” Clark said. “We’d meet outside of class once a week, and I’d meet with my lab teaching assistant, Stephanie Sparks. They wanted to make sure that I got everything out of the class that I could.”

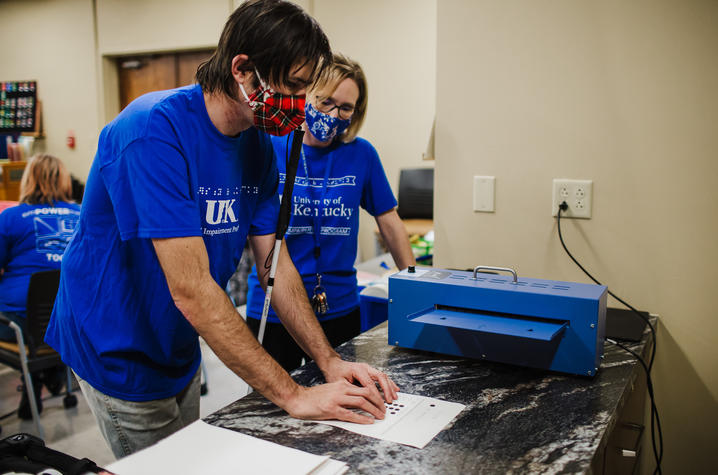

Ratajeski also used the UK Disability Resource Center’s (DRC) “Pictures in a Flash” (PIAF) fuser machine to print out materials for Clark. The PIAF allows a black-and-white graphic printed on special capsule paper to swell when the printed areas are exposed to heat from the machine.

With Clark’s guidance, support from the DRC and online geoscience education journals, Ratajeski worked tirelessly to make the course as engaging as he could for his student.

Clark said it ended up being one of the most challenging courses she’s ever taken — but not because of a lack of access.

“It made me want to try just as hard, because I knew there were people who truly wanted me to succeed,” she said.

In 2017, the DRC presented Ratajeski with its “Breaking Barriers Award,” which recognizes faculty and staff whose efforts allow students to fully participate in their classes and the UK community.

After that semester ended, Ratajeski thought their efforts could potentially benefit other students and instructors. That’s when he decided to write a grant proposal to the American Geophysical Union for the creation of an online tactile graphics repository. This would allow instructors to easily access and print tactile graphics for students who are blind and visually impaired.

According to Ratajeski, the geosciences are underrepresented relative to other STEM fields in the few online collections of tactile graphics that exist.

“I think this situation is surprising and troubling given that these resources are key to advancing accessibility and participation of students who are blind in geoscience and other STEM fields,” he said.

His proposal was funded, and he partnered with the International Association for Geoscience Diversity which agreed to host the repository on their website.

He also partnered with Clark, his former student who first made him aware of these accessibility issues. She agreed to serve as a consultant for the project.

“It was really cool to see that he didn't forget about me after I left,” Clark said. “A lot of professors won’t remember all the stuff that they needed to do to help me, but Dr. Ratajeski realized these accessibility issues have to be a problem somewhere else. By creating this online database, he knew more people could benefit from it than just me.”

Ratajeski also collaborated with Jack Reed at Stanford University, who assisted with web development, and with Donna Lee, clinical associate professor and visual impairment program faculty chair in the UK College of Education. As an expert in Braille and tactile graphic design, Lee offered her expertise in fine-tuning and processing the graphics.

“A tactile graphic is more than just a raised image — there need to be different elements to make it tactually distinct,” Lee said. “I often tell my students the hardest thing is to stop thinking visually, but to think with your fingers and how things feel versus what they look like.”

While the DRC offers a PIAF printer to create raised images, Lee said being able to design unique, high-quality, technical graphics can take a lot of extra work. That’s where she hopes her program can help.

Currently, Lee and 14 graduate students in her “Methods of Teaching Students with Visual Impairments” course are providing their services as editors on the project. The goal is to ensure the best possible graphics are available for any student who may need them.

Lee said that collaboration is the key to this project's success.

“My students and I can certainly look at tactile graphics standards and apply them to the images, as well as ensure the Braille is accurate, but we are not experts in geosciences,” she said. “While reviewing several images with Dr. Ratajeski, I quickly learned that certain patterns have meaning in the geoscience world, thus applying that knowledge to the selection of textures for the tactile graphics was important.”

One of Lee’s students, Kenneth Quinn, who is blind, is also serving as a reviewer. Quinn said by applying universal learning design and taking a collaborative approach, students with visual impairments can learn and work side-by-side with sighted students.

“I believe that collaboration is the key to anything, and this is especially true when you are concerning yourself with education and the STEM fields,” Quinn said.

The project, already available online, currently includes more than 80 black-and-white vector graphics suitable for printing on a PIAF printer. They represent topics and themes within introductory geoscience courses, are designed with principles of tactile graphic design, and are annotated and labeled in Braille. The graphics cover a wide variety of topics, including minerals, rocks, volcanoes, the Earth’s interior, geologic structures, geologic maps and cross-sections, plate tectonics, glaciers, coasts, mass wasting, soils, geochronology and climate change.

Ratajeski will present the resource in a national meeting of geoscientists and geoscience educators later this year, and the team plans to invite other geoscience instructors to contribute their own graphics to the repository.

Besides benefiting college instructors and their students, they also hope the graphics will be used in high schools.

“One of the things I love about geology is its visual nature,” Ratajeski said. “Geologists tend to think in terms of pictures, sketches and diagrams, and they want their students to appreciate their planet in as much visual detail as possible. I think that's the main reason why I wanted to make this resource: to make it easier to share the visual nature of geology with every student, regardless of ability.”

“I've seen an increase in students like Sydney pursuing careers in STEM, so there is even more of a need for these resources than ever before,” Lee said. “I commend Dr. Ratajeski for creating such a wonderful experience for Sydney. Clearly the hard work has paid off, as she is a successful graduate of UK. What better reward can a teacher ask for than to see your students succeed?"

After graduating from UK, Clark went to graduate school at Western Kentucky University and earned her master’s in public health while doing research on disability inclusion and emergency and disaster preparedness. She is currently working as an epidemiologist for the state of Kentucky and hopes to continue her work in the field of accessibility and inclusion for people with disabilities.

“There’s a huge chunk of our population that has a disability, and they already face enough challenges as is,” Clark said. “Then to go into a society that's not really made for us, and to have to fight just to get what everyone else gets normally, is really daunting. You can tell by the numbers of unemployment in the disability community.”

Clark said people like Ratajeski give her hope.

“There are so many doors that can be opened, if there are more people like him willing to help,” she said.

The Geoscience Tactile Image repository is available online now at https://tactileimages.theiagd.org/.

UK instructors interested in making their courses more accessible for students who are blind and visually impaired should contact the Disability Resource Center at www.uky.edu/DisabilityResourceCenter/ or email drc@uky.edu.

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.