New Pacemaker Technique Puts KCH Patient on the Road to Stardom

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 20, 2020) – 12-year-old Elysia Adams has big dreams.

An aspiring singer and actress, Elysia already has a professional contract, performed in several local musicals, and will be, in her words, “bigger than Taylor Swift.”

But for Elysia, her journey to the top hasn’t been smooth. In fact, it was almost over before it began.

Her mother, Katie, describes a textbook pregnancy until her 20th week ultrasound. Elysia’s heartbeat, which should be between 120 and 160 beats per minute, had dropped to 100. Two weeks later, it was 52. Katie and her husband Ryan were told there was little chance of their baby’s survival. This was devastating news, compounded by the fact the couple had already experienced a miscarriage.

“We’re thinking, we’re going through this again,” said Ryan.

The diagnosis was complete congenital heart block, a condition that affects the electrical system of the heart and disrupts normal heart rhythm. The Adams were told that if their baby survived, she would need a pacemaker to restore the heart’s normal function.

Elysia didn’t just survive; she thrived. While her heart rate at birth was low, she was still a happy, high-energy baby. It wasn’t until she was two years old when she was diagnosed with a leaky valve did doctors revisit the necessity of a pacemaker.

“With complete congenital heart block, there’s a problem with how the electricity transmits from the top heart chambers to the bottom chambers,” said Dr. Shaun Mohan, pediatric electrophysiologist in Kentucky Children’s Hospital’s Joint Pediatric Heart Care Program. “As a result, Elysia has a low heart rate at baseline, which affects how well her heart squeezes and prevents her from being more active with her peers during play or other childhood activities.”

For babies and children with heart block, cardiologists and electrophysiologists are limited by the size of the child’s blood vessels. With adult pacemakers, the electrical leads are inserted into the heart through the veins that drain into the heart. In children, the veins are too small and the risk of damage and occlusion of the veins is too high. The solution is to place the leads on the outside of the heart and the battery placed in the infant or child’s abdomen. This procedure is just a stop gap until the leads or battery fails, usually as the child approaches the pre-adolescent or adolescent years.

“We try to get them to their preteen or teenage years, usually after their big growth spurt,” said Mohan. “Then we can upgrade them to an adult-sized pacemaker if we feel it is safe to do so.”

By age twelve, Elysia was experiencing shortness of breath. The leads in her pacemaker were damaged and needed to be replaced. Pacemakers in children are uncommon; they are more typically found in older adults with heart disease. The traditional method of inserting a pacemaker is for electrophysiologists to access the veins to the heart in the chest from the front, just under the collarbone. The leads are inserted through the veins, and the battery that powers the device sits under the skin just below the collarbone. This procedure is invasive and leaves visible scarring. In more slender patients, the outline of the battery is visible.

“For older people with heart disease, they may not care about the scar or that the battery is visible,” said Dr. John Gurley, director of the structural heart program in UK HealthCare’s Gill Heart and Vascular Institute. “But for some people, regardless of how old they are, every time they look in the mirror, they don’t want to see a big scar or a bump sticking out of their chest as a reminder they have heart disease.”

Gurley collaborated with Henry Vásconez, a plastic surgeon at UK HealthCare. Vásconez was describing the process in which breast implants were inserted through an incision in the armpit. Could pacemakers, Gurley posited, be inserted the same way?

“Just because you’re old or young, it doesn’t mean that body image isn’t important,” said Gurley. “Plastic surgery is used to maintain self-esteem, right? Why shouldn’t we borrow their techniques for our cardiac devices?”

“I’ve had a long interest in using different techniques for making cosmetic device implants and using plastic techniques for closing wounds and hiding implants,” Gurley continued. “I approached Dr. Vásconez about using a transaxillary approach. And he was nice enough to work with me on some cases and taught me this technique.”

“There have been studies done about people with devices, and they have a higher rate of depression, anxiety and their sense of self-worth is affected by just having a device put in, independent of the condition,” said Mohan. “And that’s been definitely shown in children, and something we should be sensitive of. When we first put in a device in any pediatric patient, I spend a little extra time asking, how is so-and-so doing? Are they doing OK adjusting with their friends? Are they able to play with their classmates? Do they have a good sense of self being and worth?”

When it came time to replace Elysia’s device, Mohan presented her parents with the option of using this new technique.

“We trusted Dr. Mohan and his experience,” said Katie. “I looked him and said, what would you do if this was your child? He said, 'I have a daughter, and this is what I would do.'”

“With her prior surgeries, she already had some scarring that was visible, and with this new procedure, there wasn’t going to be any visible scarring or seeing the bulge of the device,” said Ryan. “We thought it was worth the minimal risk that came with the procedure.”

Mohan and Gurley discussed the potential risks that came with inserting pacemakers in children using the traditional surgical approach. It’s difficult, they said, to gauge how children, particularly girls, will grow and develop during puberty and there’s risk of damaging or destroying breast tissue. With the transaxillary approach, the device is inserted through the armpit and the battery is placed behind the chest muscles, rather than under the skin in the front. The result is no visible scarring nor outline of the device battery.

Mohan and Gurley attribute the procedure’s success to having so many subspecialties in close proximity.

“There are times when there is overlap [in subspecialties],” said Gurley. “And this is an institution where you have friends with excellent skill sets, you can say ‘Hey, I need your help with an idea.’ ”

“This is one of the benefits of being in a combined pediatric and adult medical institution,” said Mohan.

As for Elysia, she hardly gives her pacemaker a second thought. The battery in her pacemaker should last another 15 years, and she’ll continue to have follow up care about once a year.

“I never even think about it or feel it,” she said.

“Early on, she was a little insecure, because it made her feel different from kids her age, and it’s not common for kids this young to have pacemakers,” said Ryan. “But the older she’s gotten, she’s embraced it more, she and takes ownership of it.”

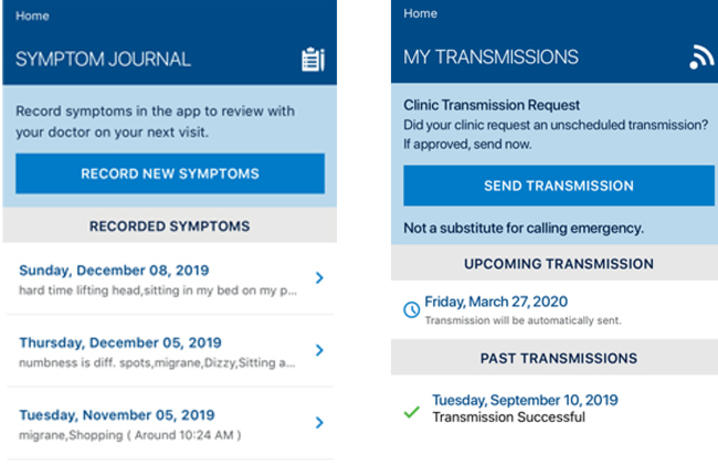

Elysia can monitor her device through an app on her phone. Unlike other kids her age, she legitimately needs to have her phone with her at all times. And though her experience has been harrowing at times, it led to some amazing opportunities. After participating the Go Red For Heart Fashion Show, an event hosted by the American Heart Association, Elysia began taking classes at Images Model and Talent Agency. In the summer of 2019, Elysia traveled to New York and competed in an international model and talent competition. It was right after she returned that she signed a contract with a talent management company in Los Angeles. She is already auditioning for television pilots and will travel to LA with her family during spring break for more audition opportunities.

“At first she didn’t want to be different,” said Katie. “But then she did the fashion show for the American Heart Association and wanted to tell her story.”

“She found her passion and what she wants to do,” said Ryan. “It is a beautiful road that she’s taken to get to this point.”

Even if Elysia wasn’t planning to conquer the world as the next Taylor Swift and pursue a career in a field where appearances matter, Gurley and Mohan still would have the same empathy for their young patient.

“It takes a little longer, and it’s not our standard approach,” said Gurley. “So we spend an extra hour with her case. What do the next 15 years look like for her? Through her teens and early 20s, that’s when people find themselves. We’re willing to take the extra time to do something that’s really going to make someone feel good about themselves for the next 20 years, when it’s the most important time of their life.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.