Previously Isolated Art Form Debuts at UK

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 23, 2011) — Bob Haven, associate professor of costume technology at the University of Kentucky, is renowned for his embroidery and beadwork. His skills are highly sought after from the couture fashion houses of Paris, to instructional videos on YouTube and still his phone rings off the hook with teaching requests.

In 2002, the consummate teacher became a student again. During an 18-day traditional arts tour of Japan, he came upon a piece of embroidery that he'd never seen before.

"I couldn't speak Japanese, and the artist couldn't speak English, but we were communicating through the embroidery stitches," Haven said. "I had never seen anything like this. And I really wanted to know how she did this?"

This Kyoto artist's gift of pink silk thread was just the start to Haven's relationship with Japanese embroidery. Upon returning to Lexington, Haven looked up the ancient art form and found out about the Japanese Embroidery Center in Atlanta. He began taking classes there in 2003.

The thread is the key difference between Japanese embroidery and other stitching, according to Haven.

"While other forms of embroidery are beautiful unto themselves, no one else uses flat silk," he said."When this silk is twisted into thread, it reflects light differently than any other material. That's truly what is so magical about it. One color can emit so many shades that the garment is shimmering."

[IMAGE1]

The Art Museum at UK, in partnership with the UK College of Fine Arts and the UK Asia Center welcomed an elaborate display of Japanese embroidery to Lexington in April.

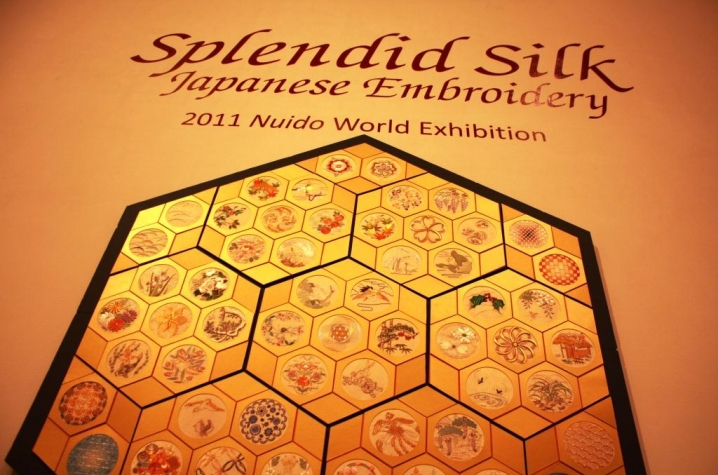

Jointly created by the Japanese Embroidery Center in Atlanta and Kurenai-kai, LTD in Japan, "Splendid Silk: Japanese Embroidery" features works by contemporary artists who have re-created ancient traditional designs on scrolls, obi, and fukusa (gift covers). Lexington is the only U.S. venue to host this global exhibition, offered every four years.

Japan's 300 years of isolation synthesized its culture and refines its use of color and design. "Japanese embroidery is simple and elegant," said Haven. "It's handcrafted and made to last."

But traditional Japanese embroidery has evolved and expanded, as Splendid Silk features works by more than eleven hundred artists from 16 countries on five continents. The exhibit's Fractal Project is a culmination of that expansion, bringing together the embroidery works of hundreds of stitches from around the world into one unified piece of art.

Each design is the size of a compact disk, embroidered with an idea that has meaning to the individual needle worker, reflecting global design motifs but worked in traditional Japanese stitching techniques. "Many of the fractals display pride for country," Haven said, "…a fleur-de-lis for France, or red and white roses for England."

One of Haven's favorite fractals tells the story of an English family's love and loss firsthand. Upon first look, the square is simply the recreation of five fuchsia and white columbine flowers.

"If you look closely, you can see that two of the petals on two different flowers are intertwined," Haven said. "The creator of this fractal lost her husband, as signified by a white flower still intertwined with one fuchsia flower. There are also three buds, signifying the couple's three children. The image represents the family. There's a story behind the simple and beautiful floral image."

[IMAGE3]

Japanese embroidery master Shuji Tamura is using the previously closed art form to open up a dialogue around the world. "He's really bringing people together," said Haven, who is two-thirds of the way through the nine-phase Japanese embroidery curriculum. "The emotional and personal dedication to this art is different than any other embroidery I've ever done."

The spirituality of the stitching is as important to the artist as the stitch itself. Japanese embroiderers continually strive to make the next stitch better than the last one, according to Haven. The hands become an ambassador of the soul.

"Japanese embroidery is not for the faint of heart," Haven said . "When you're in Atlanta at the center, you are surrounded by silence, except for the pluck and squeak of the needle. I find the silence relaxing. How much you stitch doesn't really matter. I think that's the difference between craft and art."

The practice of Japanese embroidery is not for everyone, and this consummate teacher may never be ready to impart the art at UK. Transitioning from a master/apprentice-style of learning to class curriculum is "a quantum leap," Haven said. "Even though Mr. Tamura has divided up the lessons into smaller and more accessible units, a lot of questions as to why we do certain things remain. As a professor, it's easier for me to fill in the blanks, but as a student it's difficult to get used to."