Provost’s first-generation experience drives passion, persistence in leadership

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Nov. 8, 2023) — The University of Kentucky is joining higher education institutions across the country in celebration of National First-Generation Week, hosted by UK's Office for Student Success.

At UK, around 25% of students are first-generation students, meaning that their parents did not complete a four-year college or university degree. The University of Kentucky’s first-generation enrollment trajectory has increased degree and certificate production from about 1,200 in 2017-18 to almost 1,900 in 2022-23.

As part of National First-Generation Week, UKNow is resharing the story below from earlier this semester - which tells the first-gen story of University of Kentucky Provost and Co-Executive Vice President for Health Affairs (EVPHA) Robert DiPaola, M.D.

Any time Robert DiPaola was sick as a child, his parents took him to see the family physician who always called the young boy “doctor.” DiPaola conceded, “I don’t know if he called every kid that,” but it made a difference.

What people — especially children — hear and see influences what they believe about themselves.

DiPaola’s father, Louis, was a voracious reader. Every day, in the quiet, early morning hours before his family awoke, his father would sit in his chair, hunched over a book, surrounded by many more books. He read to understand the world. He read to find answers to the questions he contemplated. And he used what he read to fix things, solve problems and expand the world views of his friends and family.

His father worked as a technician for AT&T for much of his career, climbing the managerial ranks. In addition to being skilled with his hands, he was a lifelong learner.

He always encouraged his family to read, but he never forced it. He simply modeled it.

“People always thought Dad was so smart because he read a lot and — and in retrospect, he was very intuitive,” DiPaola said. “But I don’t think he ever got to ask himself what he was passionate about and pursue a career based on his passion. Honestly, he found opportunity in life through us. He worked hard, but he felt really good about us being successful.”

To this day, Louis DiPaola’s son, Robert, reads every morning.

Robert DiPaola, M.D., serves as the provost and co-executive vice president for health affairs at the University of Kentucky. By all accounts, DiPaola never should have left New Jersey or become a physician. He never should have been the first in his family to graduate college or reach levels of leadership at prestigious universities, but he did.

All four of DiPaola’s grandparents emigrated from Italy to the U.S. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, and was the oldest of three boys. His parents raised them with their multigenerational, multicultural extended family and with aspirations of attaining their wildest dreams.

“The thing my parents always told me was to find something I am passionate about, DiPaola said. “My dad, in particular, always encouraged me to follow my passion so I could make a difference in the world.”

His passion, persistence and ability to bring people together catapulted him from his working-class childhood on the east coast to where he is today.

Discovering his passion

The DiPaola family moved from New York to New Jersey in 1976 because Louis believed the area had a better public school system including a community college. DiPaola graduated from West Morris Central High School, where several years later, his own children, too, would attend. Although both his parents graduated high school, no one in his family had pursued higher education. “I really didn’t know what it was like at that point to think about college and careers and what opportunities there might be,” he said. But his parents encouraged him to enroll at County College of Morris (CCM) in Randolph, New Jersey.

“When he was in high school and thinking about going to college, we discussed it, and his dad suggested he go to CCM as a starting point,” DiPaola’s mother, Dolores said, “Lou always encouraged education and felt the county college was a good start that was affordable.”

CCM provided DiPaola with an opportunity to explore different areas, to test ideas about how he may want his future to look. Although his major was humanities, he discovered an interest in biology, which led him to health care. But he did not know what a career in health care could look like or if it was possible for him to have one.

At CCM, there was an anatomy and physiology instructor he admired. At some point, DiPaola approached him about pursuing a career in health care. The instructor discouraged him from medicine. He tried persuading him to consider alternative career paths because of how difficult it was to get into medical school.

However, DiPaola persevered. He remembered, “I still had this sense, especially from my father, that I had to do what I was passionate about. I felt this sense of persistence, and I kind of wanted to prove (my instructor) wrong.”

The cross-country move

Around this time, close friends of DiPaola’s parents who lived next door had a different idea. Their names were Ellen and A.J. Hiltenbrand, they were both college graduates and A.J. was an executive at a number of companies. Near the end of DiPaola’s time at CCM, the Hiltenbrands were preparing to move to Utah for business. They knew DiPaola dreamed of becoming a physician, and they encouraged him to continue his education at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“I had never actually been to Utah before applying. The first time I went to the university was when I enrolled and started classes,” DiPaola said. He transferred as many credits as he could, but “not everything transferred. The system was not as great then as we have it now here at UK, for example.”

He took courses in English and the humanities, which he credits with his effective communication skills today. He even retook a few introductory classes to smooth his transition.

“I don’t know if you want to call it ‘imposter syndrome,’ or what,” DiPaola said. “But I always felt like I had to work harder than everyone else. And so, day and night, I worked hard.”

The Hiltenbrands continued to support him, hosting him for homecooked meals on the weekends, serving as surrogate parents while DiPaola was away from New Jersey.

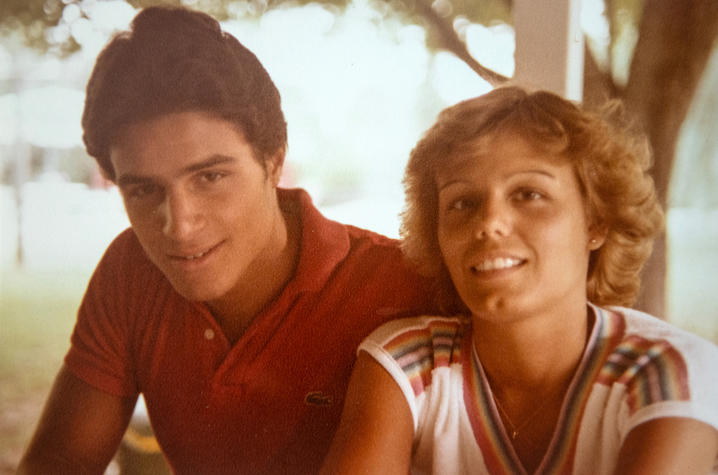

One semester at the University of Utah was particularly rough. He was alone on campus, and Marcie — who would eventually become his wife — had not yet moved to Utah. He was feeling homesick, for no particular reason that he remembers, and he decided to withdraw.

While DiPaola was waiting in line to unenroll from the university, Ellen drove to campus to stop him. “Don’t worry about making it all semester,” she told him. “Just make it one more week.”

And he did. Then he finished the semester. And he graduated from the University of Utah in 1984, summa cum laude.

One of the reasons he chose the University of Utah was because it was a comprehensive academic health system, much like UK, where he could transition seamlessly from undergraduate studies to medical school. As DiPaola prepared to take the MCAT, though, he felt like other students seemed to know exactly what to do. They were taking prep courses, but he had no idea how to prepare. Whether or not he was at a disadvantage, he attributes this feeling disadvantaged to being the first in his family to go to college.

So, he did the only thing he knew to do. He studied hard.

After getting accepted to multiple medical schools, including the University of Utah, someone notified him that he was lacking credit for one course: American history. He learned a semester’s worth of material in two weeks and tested out of the course.

By this time, he and Marcie were married, and staying in Utah was the most financially affordable thing to do. Over the coming years, they would have three sons, and DiPaola would continue following his dreams of becoming a health care professional.

Becoming a physician

While in medical school, he wanted to do research. He found an opportunity to do part-time biomedical research with John Ward, M.D., an oncologist who modeled a passion for research and clinical care that he cultivated in DiPaola.

In 1988, DiPaola was selected to present in Carmel, California, at the Western Student Medical Research Forum on his research project, “Iron Recycling in Microphages.” This sparked an interest in sharing his research with the broader academic community.

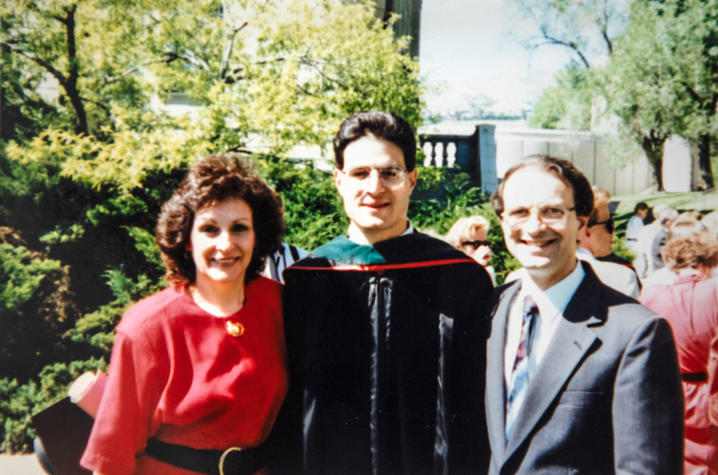

After graduating from medical school, he completed an internship and his residency in internal medicine at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. In 1991, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to participate in a fellowship on hematology-oncology at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I ended up choosing oncology because I aligned with and was passionate about this particular area because of Dr. Ward,” he said. “It ended up being my path because a faculty mentor made a difference.”

Leading through service in New Jersey, Kentucky

In 1994, DiPaola and his family moved home to join the faculty of the Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick, which later became part of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

As a faculty physician and researcher, DiPaola liked treating patients, but he loved training future physicians and developing new treatments through research that could reach more patients than he alone could ever care for. He said, “If someone asked me how I got from one point to another in my career, I would say, when asked to take on an opportunity to help and make a bigger difference, I was always eager to step up. Before taking a next step, I would ask, ‘Could this help me be more impactful?’”

He frequently was asked to take on leadership positions. Notably, he served on the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Initial Review Group and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NCI Committee. The latter evaluates current NCI-designated cancer centers and those seeking designation. Of the many cancer centers he reviewed during his tenure, he distinctly remembers visiting Kentucky to review the Markey Cancer Center.

Years later, in 2016, when DiPaola and his wife were empty nesters, they relocated to Lexington, Kentucky where he had been appointed dean of the UK College of Medicine.

Eventually, two of his three sons moved to the Lexington area, as did his mother, Dolores. Central Kentucky has become the DiPaolas’ home.

In 2021, UK President Eli Capilouto asked DiPaola to serve as acting provost. The following year, after a rigorous national search, DiPaola became the official provost. In December 2022, DiPaola joined Eric Monday, UK’s executive vice president for finance and administration, as acting co-executive vice presidents for health affairs.

In every role, DiPaola has found opportunities to lead and serve.

“In leadership positions, you do have to give some things up. I obviously cannot go to clinic every day, and I wish I could,” DiPaola said. “I miss having a relationship with my patients, but that is what drives me to have the right kind of relationship with those I help today. Whether I am serving faculty or staff or whomever, I want to do my best for them.”

“In the Office of the Provost, we are a unit that serves. We are here to serve — to serve our faculty, to serve our community, to serve the Commonwealth. And ‘service’ is not a passive word when I use it. It is active,” he said.

To demonstrate this attitude, DiPaola insists teamwork — bringing together different people with a common goal — is crucial to success.

Fostering a culture of collaboration

When President Capilouto asked him to serve as acting provost, DiPaola considered it an opportunity to foster a greater sense of working together.

He said, “When it comes to advancing Kentucky, how much better can we get than collaborating as one enterprise to figure out ways to enhance the workforce, to improve health care disparities, to reduce socioeconomic disparities and to do good? Solving Kentucky’s greatest problems requires us to work together as a team. It requires us to ask, ‘What can we do better together?’”

Rather than considering this idea to be interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary, DiPaola prefers the term “transdisciplinary.” In February, DiPaola explained this concept as “bringing experts together, early in the process to focus on solving a problem collaboratively, to help our students today and Kentucky’s workforce tomorrow.”

DiPaola’s time at UK illustrates his commitment to bringing together different people to have a greater impact. His prior experience with accreditation positioned him well to lead the university’s efforts with other leadership to develop our new strategic plan, the UK-PURPOSE.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020, DiPaola formed the START Team to ensure the entire enterprise — including the academic and health systems — was prepared to face the challenges presented by COVID. The START Team comprised experts, innovators and leaders throughout UK, and they reimagined our approach to education, research, service and care to remain operational during the pandemic.

As part of UK-PURPOSE, DiPaola contributed to the develop of the university’s quality enhancement plan (QEP), a crucial part of UK’s accreditation process with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). The QEP is called Transdisciplinary Educational approaches to advance Kentucky (TEK). TEK is a multifaceted approach to introducing and embedding transdisciplinary, collaborate work in the university culture.

In summer 2023, President Capilouto empaneled a committee, led by DiPaola, called UK Advancing Data utilization for Value in Academics for National and Campus-wide Excellence, or UK ADVANCE, to help guide the university in the responsible use of generative artificial intelligence (AI).

Throughout UK’s campus, DiPaola has elevated this idea of approaching all work — whether teaching, researching, serving or caring — in a transdisciplinary and cooperative manner.

Understanding the first-generation experience

His dedication to transdisciplinary work is evident in his belief that students need a network of people — family, friends, advisors and, especially, mentors — to support them.

Families are important in encouraging their students while in college. Friends keep students engaged and healthy. Advisors guide students through college, which can be a notoriously complex process, particularly for first-generation students.

“Our Office for Student Success and colleges do an incredible job of ensuring our students have access to this guidance and encouragement,” he said.

And as for mentors, DiPaola said, “I think a lot of my choices along the way were because of people I happened to bump into that became mentors, and it worked out. In college, mentors help you see what life is like — what it could be.”

While in college, DiPaola needed to identify mentors.

“As a first-generation student, finding mentors, especially faculty mentors, was key for me,” he said. “I encourage all first-generation college students to do the same.”

When asked what first-generation students should do, he answers with four recommendations. The advice easily could apply to any student. Or, honestly, anyone.

- Build your support structure of family, friends and mentors.

- Find and follow your passion for a greater purpose.

- Read a lot.

- Stay persistent.

DiPaola’s career embodies these four principles.

“Reflecting on my life, I can see that my journey has been a series of challenges — of different doors opening — and as long as I was following my passion, I said yes. As long as I could make an even greater impact, I would be fine.”

A family motivated by passion, persistence

DiPaola’s life has been defined by passion, persistence and bringing people together.

When asked if the feeling of having to work harder than everyone else is still with him, DiPaola said, “Probably to some degree, yes. I have gotten more comfortable, more confident, but probably.”

When asked what he is proudest of — of course it is his family — but professionally, he says it is when his colleagues succeed. “What I see coming out of our colleges — that gets me excited. I see their achievements — awards, proposals, programs — and I think, ‘Wow, this is incredible!’”

Passion, persistence and collaboration are part of DiPaola’s identity because they are part of his family.

Many years ago, his father was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a severe lung disease that worsens over time. Near the end of his life, he was increasingly hospitalized. During one of his final hospitalizations, DiPaola asked his father, “Do you remember how you always told us that we could become anything we wanted to as long as we put our minds to it?”

Of course, his father remembered. According to his family, he said it all the time. His son expressed to him how much his consistent encouragement meant to him. But he told his father he was struggling to reconcile the family's mantra with his father’s present condition. “No matter how hard we try, none of us can change this,” he said.

His dad replied, “Well, Robert, you know, there are limitations.” After chuckling, he said, “Maybe it’s good I never told you that.”

Dolores, too, remembers how frequently her husband would give this advice to their children. “When Robert told us he’d like to become a doctor, he said that he didn’t think he could do it. His dad told him, ‘You can be anything you want to be if you put your mind to it!’” she remembered.

“And he did put his mind to it. He continues to help others, just like his dad did,” she said. “And here he is!”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.