UK HDI Staff Lead the Conversation on the Meaning of Disability Pride

LEXINGTON, Ky. (July 29, 2022) — It’s been 32 years and three days since the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. Earlier that same year, in March 1990, over a thousand disability rights activists marched from the White House to the U.S. Capitol after months of inaction by Congress, where about 60 protesters abandoned their mobility aids and began ascending the Capitol entrance’s 83 steps, forcing Congress to “see” them and the urgency of the ADA. The protest became known as the “Capitol Crawl,” which was part of a series of disability rights protests in Washington, D.C. that week. The ADA, which prohibits discrimination on the basis on disability, was passed the following July, initiating a monumental shift for the nation that continues to have a direct impact on those living with a disability. In Kentucky, that’s one in three adults.

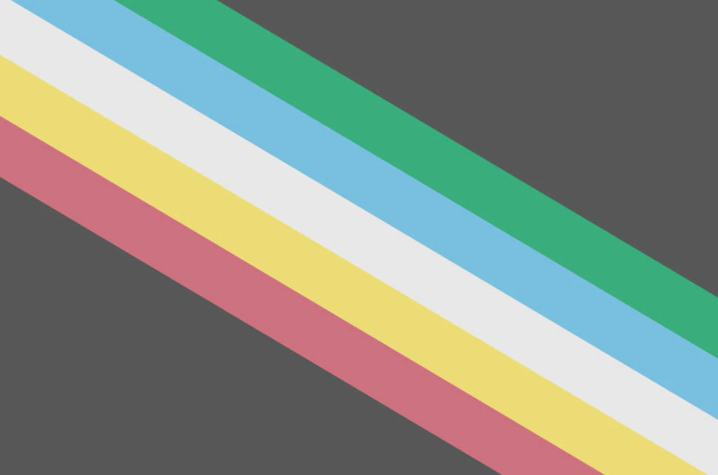

Disability Pride Month is celebrated in July to commemorate the ADA’s passing into law and to honor the disability rights activists who fought for what the rest of the nation had gained decades prior. Annual parades in Boston, Chicago and New York exude joy and grit, while recognition of Disability Pride Month rapidly grows more into the nationwide consciousness each year.

Today, every state has at least one University Center on Disability. Kentucky’s is the Human Development Institute (HDI), housed at the University of Kentucky, with over 300 staff members and 70 ongoing projects and initiatives such as Lettercase, RETAIN and UK’s undergraduate Universal Design certificate. HDI offers regular community resources along with pop-up seminars such as its upcoming webinar on writing inclusive job descriptions.

For some, “disability pride” seems a counterintuitive term. HDI staff members Jacob Mason, Jason Jones and Phillip Rumrill, Ph.D., who each live with one or more disabilities themselves, shed light on both the bright spots and the challenges they encounter, what it means to embody disability pride and how we can all work toward creating an accessible world for all.

Jason Jones is a disability specialist at HDI. He had his accident the same year the ADA was signed into law, and he’s an active board member on Lexington-Fayette Commission for People with Disabilities.

“When we talk about pride, I’m proud of the fact that I — through a disability or in spite of a disability — have still been able to accomplish the things that I wanted to do in life and to show the world that people who are different in some way, no matter what that is, are capable of not only just functioning, but thriving in the world, too,” Jones said.

For Jones, disability pride looks like getting out into the world and bringing people’s attention to the accessibility problems of the built environment. When he’s unable to access parking or cannot fit his wheelchair through the bathroom door, he sees value in respectfully approaching a business owner to say this is why this matters.

“There’s no better cliche than ‘you catch more flies with honey,’” Jones said.

Jones says that as a parent, he wants to be out doing things with his sons.

“I want other parents to (think), ‘Hey, we shouldn’t plan things in the building that Jason can’t get into, because his kids play golf and are in swimming and do all the things all the other kids do,’” Jones said. “So get out in the world, assess the world, and find a good message to give to the world in order for the world to be a better place.”

Jacob Mason is a data specialist at HDI. He says his disabilities help him better understand and contextualize the data he works with. Mason appreciates Disability Pride Month, because much like HDI, he says, Disability Pride is focused on celebrating all disabilities, rather than just specific ones.

“I have cerebral palsy and autism. One aspect that makes me proud is it helped me through college with memorization,” said Mason. “There are always going to be challenges, but it’s sort of nice to have the bright sides of different things and to think about them. Those brighter sides make you more unique and proud of it.”

Mason notices that when he goes to his doctor’s appointments, providers frequently speak to his mom instead of to him. He recognizes that it’s perhaps easier for the providers to direct the conversation to his mom because he has a speech impairment.

“However, you want (the providers) to acknowledge you,” said Mason. “Something new can always come up, and it’s like they only pay attention to the one that’s talking more clearly (instead of) addressing both people in the room.”

To this, Phillip Rumrill said, “It feels like, Jacob, you kind of always have to be on duty or on alert, and you have to give all of this more thought. … not everyone wants to be an advocate. Wouldn’t it be great if we didn’t need to be all the time?”

Rumrill is the director of research and training at HDI, as well as a faculty member in the UK College of Education’s Counselor Education program. He says his own experiences of support and encouragement when he became legally blind at the age of 15 due to a neurological condition initiated his interest in how people adjust to disability.

“Look at all the festivals you see — sexual orientation, gender, religion, whatever it might be … people take pride in those characteristics because it makes them who they are,” Rumrill said. “(Disability) is not something that needs to be pitied. … It’s actually something we can take pride in and connect around commonalities by embracing the fact that we’re all different and we’ve got groups of people who share one identity in common as they come together.”

Rumrill points out that disability rights and advocacy began many years ago with society “trying to determine how they would tolerate disability.”

“It came across as charity. … that’s not what we’re looking for,” said Rumrill.

Likewise, Mason is clear that he doesn’t want people to “just be aware” of him. He wants to be accepted.

To this, Rumrill brought up National Disability Employment Awareness, an annual October initiative focused on educating non-disabled people about disabilities. Rumrill, Mason and Jones were all in agreement that Disability Pride Month is a better opportunity for education from people with disabilities, because nondisabled people should not be at the center of these conversations. They agree that something HDI does very well is involving people with disabilities in decisions that affect their disabilities.

“Let’s take autism, for example. If we have a policy or program that is going to be involved with the autism community, there will surely be people with autism on that board. Absolutely, 100% of the time,” said Rumrill. “Don’t make decisions without us that affect us.”

As we exit this Disability Pride Month, we, the University of Kentucky, owe it to ourselves, our friends and our colleagues to prioritize accommodation the first time around, to seek out education on creating inclusive environments, and to restructure our built environment with our Wildcats with disabilities at the forefront of the process.

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.