UK Remembers: 20 Years Later, Faculty and Staff Share Stories of 9/11

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Sept. 10. 2021) — Tomorrow, the nation will commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11 — a day that lives in infamy after nearly 3,000 people lost their lives in what was the deadliest terrorist attack in human history.

Like most places, Sept. 11, 2001 at the University of Kentucky started out as an ordinary, late summer day. But as the events of that tragic morning unfolded, the university community, like everyone, was never quite the same.

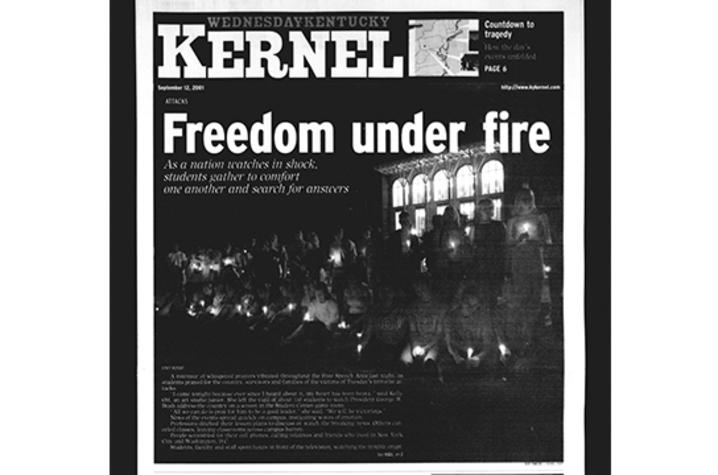

After the series of attacks occurred, classes were canceled for the rest of the day. According to the Kentucky Kernel, students quickly mobilized to donate blood and relief funds. Later that evening, a candlelight vigil took place outside of the William T. Young Library.

In the following weeks, tribute walls with messages of hope and unity flooded campus, and gatherings that celebrated diversity and inclusion of students from all nationalities were organized in the wake of discrimination and hates crimes following the attacks.

The people of UK lifted each other up during those dark days that followed, and just like the nation, they came together in a spirit of resilience and unity.

While many of today’s UK students were likely too young to remember the events of 9/11 (or not yet born), many UK faculty and staff still vividly recall where they were that morning and how that day impacted their lives.

Ahead of the 20th anniversary, UKNow invited those with personal stories or connections to the 9/11 victims and their families to share their stories.

Content warning: Some of the stories below include recounts of the 9/11 violence and resulting deaths of family members and friends. Reader discretion is advised.

Carl Nathe, public address announcer for UK Football and now-retired employee of UK Public Relations and Strategic Communications, shares his story on the loss of his childhood friend in the World Trade Center attacks.

Rick Hall, and his younger brother Doug, moved in as my nextdoor neighbors in Pleasantville, New York, shortly before we both started kindergarten. Their father was a former minor league baseball player and taught the game to us — Mr. Hall took us to a baseball field anytime we wanted to learn how to hit, field, throw, run the bases, etc. Rick and I, along with Doug, became youth baseball players and added in basketball and football along the way. We all loved to listen to sports on the radio, watch games on TV or attend in-person whenever possible.

Rick remained a close friend all the way through high school and beyond. We each went to different colleges, yet still saw each other during summers. We each moved to different places in the country to begin our full-time working careers after graduation, but still kept in touch. As we began to have families of our own and lived farther apart, we were not able to see each other very much. Still, each of us remained the other’s oldest friend.

The last time we got to see each other in person was in 1998 in New York City. My entire family went to visit Rick at his office on the 104th floor of one of the twin towers of the World Trade Center. It was a wonderful 45 minutes or so, sharing stories and catching up on our respective lives. We still emailed each other after that, and had hopes to reconnect again down the road.

On Sept. 11, 2001, I was out on UK's campus working on a project when someone told me there had been a “horrible accident” and that a plane had struck one of the towers. Immediately hustling back to my office, I prayed that somehow everyone in the World Trade Center and in the plane would be OK. I turned on one of the office TVs to see what was happening and then just a couple of minutes later, a second plane crashed into the other tower. Now it was readily apparent: this was not an “accident.”

Like all of us experienced that day, there was a gnawing, sick feeling inside of me. I later learned that Rick’s building was the second one hit and that he was presumed dead, together with nearly 3,000 others. His body was not recovered from the wreckage until several weeks later.

In November, back in our hometown of Pleasantville, we held a memorial service to honor Rick and remember him. He was just 49 years old.

I have visited his gravesite on several occasions and his name is inscribed in the World Trade Center Memorial. We all miss him dearly, yet life must go on.

Janie Heath, dean of the UK College of Nursing, shares her story on living in Washington, D.C., in 2001. Her husband worked at the Pentagon, and she recalls the agonizing wait to learn if he was safe.

At exactly 8:46 a.m. my life as well as millions of others changed forever. It truly was the longest day of my life. I still vividly remember teaching Acute Care NP students at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., when word got to us that something so tragic and unimaginable was happening in our country.

We started hearing that a plane hit the World Trade Center and then we started seeing the smoke from the Pentagon and knew we were under attack.

The town was literally shut down — no communication coming in or out and traffic was at a standstill. Students started running for their lives on campus and nursing students started running to the hospital to assist in any way possible for incoming victims — except no one came.

It was so surreal and hard to comprehend the full impact of what was going on — another plane had hit the second tower of the World Trade Center and a plane had crashed into a corn field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, (and then) smoke filled the sky in Washington, D.C.

All I could think about was my husband — a U.S. Army colonel assigned to the Pentagon. I couldn’t remember if we exchanged our usual goodbyes and I love you — all phones were dead and I knew our kids were worried sick about us.

Employees started walking home while I stayed paralyzed watching the news and waiting for a call that never came, until 12 hours later when I finally made it home and heard his exhausted voice:

“I’m okay — I walked out of the Pentagon 20 minutes before the attack.”

It would be another 24 hours before I saw my husband, as “duty calls” and “the soldier” gets to work with managing the devastation of so many civilian and military lives lost that day.

To this day whenever I hear a low-flying, loud plane, I cannot help to worry is it happening again, and no matter wherever I am and I see our beautiful American flag I am so proud of what it stands for and all those that serve to protect our freedom and safety that day and every day — firefighters, police, military, emergency personnel and more.

Beth Barnes, professor and director of undergraduate studies in the UK Department of Integrated Strategic Communication, was assistant dean for professional master’s programs at Syracuse University in 2001. She remembers many students who lost family members in the attacks, and recounts coming together with a large group of students, domestic and international, in the wake of prejudice and hate crimes against those of certain nationalities.

My morning on Sept. 11, 2001 began with the fall kick-off event for the Syracuse (NY) Ad Club. I was president that year, and one of the city’s advertising agencies was hosting a fall TV preview, where we were seeing clips from the pilot episodes for the fall’s new TV series and hearing about each network’s primetime program lineup.

As has often been reported, it truly was a beautiful day. In Syracuse, a little over four hours’ drive from midtown Manhattan, there was a nip of fall in the air and the sky was cloudless and bright blue. Syracuse University had started its fall semester a few weeks earlier, so we were into the swing of classes.

The first sign that something was going on was when the mobile phones of the various station ad reps in our preview event began ringing. A call would come in, the rep would step out to answer it and then they didn’t come back. After that happened several times, the video clip we were watching was stopped and one of the agency tech people came out of the control room to tell us that a plane had hit one of the World Trade Center towers. At that point, the assumption was that it was a small private plane. We ended the meeting and everyone headed to their jobs.

I was still in my car driving to campus when the announcement came over the radio of the second plane hitting. As soon as I parked, I ran into our building, where I knew there would be TVs going. Sure enough, the building lobby was full of students, faculty and staff, all watching the news coverage. I hadn’t been inside long when the first tower fell. I particularly remember my dean, a native New Yorker, sitting in stunned silence.

As the morning continued to unfold, my next, very vivid memory, is of trying to track down my brother. He was working in Boston at the time, and flying to the West Coast fairly often. (The two planes that hit the towers were both Boston departures heading for Los Angeles.) The person who first answered the phone when I called my brother’s company just wouldn’t tell me anything, which felt like a punch to the gut. But when I called back, the person I got the second time was able to reassure me that they had seen my brother that morning and he was there and in a meeting.

By early afternoon, there was already tremendous speculation about who was behind the attacks, and already some reports of backlash against people from other countries happening. We decided to call a meeting of our master’s students; we had 200 or so across the school’s various programs, and about a third of them were international students from a range of countries. We wanted to give all of our students the chance to come together and talk, and to encourage everyone to look out for one another. I also remember being very aware that for some of our international students, terroristic violence on their own soil was something they were very used to. So, it was also a chance for them to share their experience of living with that with our domestic students.

Over the next days as more details came out and as victims were identified, I learned that the older brother of one of my students had died at the World Trade Center. He didn’t work there, but he’d been at a breakfast meeting at Windows on the World, the restaurant on the top of the North Tower. Another of our students lost her father in the attack on the Pentagon.

Syracuse University lost 30 of its graduates in the 9/11 attacks. Many Syracuse students lost family members that day; the university draws a large portion of its students from the New York metropolitan area. And, tragically, SU was no stranger to terrorism; 35 of the people killed in the Pan Am bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988 were current SU students on the way back from a semester-long study abroad program in London.

One other 9/11-related memory that has stayed with me over the years was formed more than a month after the attacks. I traveled from Syracuse to Anchorage, Alaska to lead an accreditation team at University of Alaska. All of Central New York and, I’m sure, much of the East Coast was still draped in American flags and bunting. But I wasn’t expecting to see the same thing over 4,000 miles away as I walked around Anchorage. That really brought home to me the extent of the national grief.

To this day, if I’m teaching on 9/11 at the time the first plane hit, I stop my class and ask my students to join me in a moment of silence. I’ve yet to be able to get through making that request without starting to cry.

Peter Berres, now-retired assistant dean of student affairs in the College of Health Sciences, shares his story of losing his nephew in the World Trade Center attack.

Like many Americans, my first memory of Tuesday, Sept. 11, is of the wondrously beautiful day it began as. And the unprecedented, horrific day it became.

At home (as I prepared to drive to Bowling Green for a UK meeting) and watching the incomprehensible story unfold, aware of the first plane and hoping — though I found it impossible to believe — that a small plane had accidently hit the first World Trade Center Tower, I held to that belief even as I entertained other explanations, including purposefully violent attack scenarios.

I knew that my sister’s son, Paul Kenneth Sloan, age 26, had recently moved from San Francisco to NYC with a financial-investment job. Unaware that he worked at the World Trade Center, I worried about him working close to the towers and that some of the secondary effects might threaten his safety.

Around lunch time, I phoned my sister living in California, beginning the conversation by asking “how far is Paul from the towers?” The answer came in her tone, before her words registered with me: “he works in the south tower, I just talked to him, he is okay and now leaving the building.”

Paul began descending the staircase from the 87th floor. Somewhere down, the public announcements insisted that it was more dangerous outside the building and to stay inside on your work floor. He returned to the 87th floor and called his dad, who was in a meeting in Houston, where they were watching the news accounts of the first plane. (While) telling his dad he had attempted to leave, but was persuaded back to his company’s offices, the second plane hit his building — with his dad watching — and the phone went dead.

Unable to get a plane out, my brother-in-law drove his rental car straight to San Francisco, collected his two other sons and my sister, and then drove — nonstop — from SF to NYC to meet with their daughter who lived north of city.

Days of searching hospitals, days of hope fading …. Days of collecting his personal belongings and talking to the everyday people in his life — grocers, laundry-cleaners, parking attendants, door men, neighbors — all of whom spoke of his unique kindness and gentle and genuinely engaging personality.

Crushed, they returned to California to await confirmation, wait for his body, and for a funeral and a spot to lay him to rest and a place to visit. The knock, finally, came early one morning, weeks later. Confirmation was made from a piece of thumbnail.

Plans for a funeral were abandoned, instead a memorial was held. My sister asked me to eulogize Paul, which has remained the saddest, most difficult of 10 eulogies I’ve delivered. But his was the easiest, having such incredible material from his short life: his character grounded in values and ethical standards which represent the best of us; a work ethic which drove him to do the best in everything he attempted, often building on rather ordinary qualities which he willed into excellence. And, above all, evident from the earliest times of his young life, the kindest and sweetest personality, the kind we seldom see so clearly, so early.

With all eulogies, my hope is that those qualities we admire in others will find their way into our own hearts. In the last 20 years, my thoughts return to Paul regularly as I recognize my many faults and flaws and look to Paul to remind me what a gracious, meaningful life looks like. The youngest of those I have eulogized (parents, two brothers, war buddies who ended their own lives) Paul’s short life has taught me more about being a human being than anyone. He has made me — and his friends and family — all better persons by his well-lived example than any other influence I am aware of. To that extent, Paul lives in so many people and continues to guide us and inspire us to the decent humans we are capable of being.

My heart remains heavy for my sister and her family, a burden I wish I could carry for them all.

At this 20-year anniversary, I am both proud and humbled by my sister and brother-in-law’s courage and resiliency in carrying their burden and the grace and dignity with which they have managed themselves for the betterment and comfort of their children, grandchildren, extended family and friends. Life goes on, indeed, but Paul lives on in so many of us.

Amanda Nelson, director of media and strategic relations in the UK College of Education, was a senior at UK in 2001. She shares a story of how a group of volunteers from her hometown of Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, traveled to New York City to assist with recovery efforts after 9/11.

My father was the local newspaper publisher, so we drove from Lawrenceburg to New York to report on their work. It was surreal to be in the city with people I had known my whole life as they wore Red Cross vests and prepared meals.

We were invited to go with them to the World Trade Center site to deliver packages of clean socks and freshly cut fruit to the rescue and recovery workers. I had watched 9/11 play out on campus televisions at UK, trying to process with my friends what was happening. I was nervous about how it would feel to see it in person. I recall the exhaustion on workers’ faces, being surprised by the vastness of the destruction and the smell of burning plastic. It was haunting to see the debris and dust in unusual places, like covering tombstones at St. Paul’s Chapel, and in a nearby jewelry store’s window display, frozen in time. It deepened my sense of reverence for what people experienced, and the memories of how that felt continue to be a profound part of my life.

Looking back 20 years later, I realize what a pivotal time that was globally, and also in my own life. I was on the cusp of finishing school and entering adulthood and it was the first time I saw that level of tangible fear and grief. But it showed me that, no matter how devastated they are, people keep putting one foot in front of the other to get through, and that gave me hope.

***

To read more personal accounts, UK Libraries’ Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History houses a collection of interviews and personal stories of Kentuckians surrounding their connections to Sept. 11, 2001.

- “Bourbon in Kentucky: Women in Bourbon Oral History Project” featuring Jessica Pendergrass

- “From Combat to Kentucky Oral History Project” featuring Tyler Gayheart and Ian Abney

- “Peace Corps: Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (Kentucky) Oral History Project” featuring Tara L. Lloyd

- “Quilt Alliance’s Quilter’s S.O.S. Oral History Project: American Quilt Study Group” featuring Mary Perini

- “The John G. Heyburn II Initiative for Excellence in the Federal Judiciary Oral History Project” featuring Judge Joseph H. McKinley, Jr.

- “Walter D. Huddleston Oral History Project” featuring U.S. Sen. and former Senate Select Committee on Intelligence member Walter D. Huddleston

The University of Kentucky will commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11 in multiple ways tomorrow:

- UK Army and Air Force ROTC will honor the victims of 9/11 by placing small flags in memory of each of the nearly 3,000 victims of 9/11 on the front lawn of UK's Main Building. From a podium, cadets will also read the name of each victim throughout the day. They will begin reading the names at 8:46 a.m., when the first attack occurred. Learn more here.

- UK Opera Theatre Director Everett McCorvey, along with three vocal students and alumni from the UK School of Music, will join the National Chorale, the U.S. Army Field Band and the Soldiers' Chorus at the Empty Sky Memorial Remembrance Ceremony, beginning 2 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 11, in Liberty State Park, located in Jersey City, New Jersey. Learn more here.

- This Saturday's UK vs. Missouri football game will also serve as the UK Heroes Day Football game. The game starts at 7:30 p.m. and a special ceremony will recognize all active, reserve and veteran members of the U.S. armed forces along with police, firefighters and other first responders.

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.