A Life in Photos: Q&A with Sam Abell

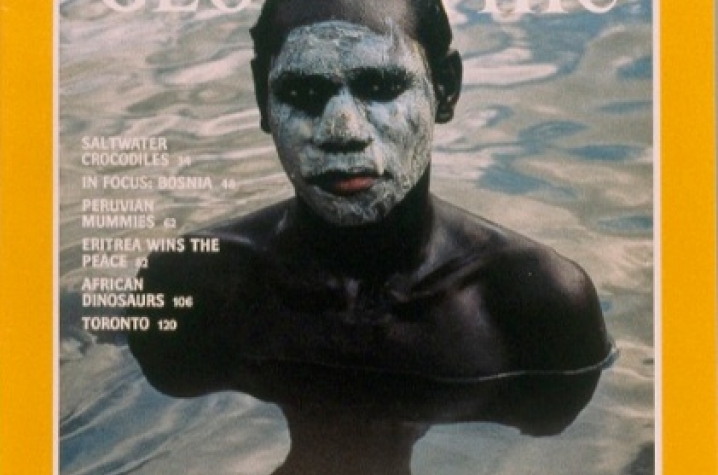

[IMAGE4]LEXINGTON, Ky. (July 20, 2012) — In 1967, University of Kentucky College of Education alumnus Sam Abell went to his first job interview. In 2001, he ended 33 years of traveling on assignment for National Geographic. Over that time, Abell's photos have become synonymous with National Geographic and taken him around the world. Later this year, Radius Books in Santa Fe, N.M., will begin publishing the "Sam Abell Library," a 16-book set that will be released in four-book sections over the next four years.

Abell recently took time out of his busy schedule to reflect on education, his life of photography and worldly travel.

Q: What got you involved in photography?

A: My father taught me photography. It was his hobby and we had a small darkroom in the fruit cellar of our basement. It was the kind of makeshift darkroom that was only dark at night. My dad also started a camera club at the high school where he taught. He and I went on camera outings together to places we both liked — circuses, working quarries, train stations. It was on these trips that I learned the priceless lesson that photography was a way to be out in life. That powerfully appealed to me. But I was also attracted to photography's expressive power. There are a lot of ways to be expressive in life but I wasn’t good at some of them. Music for instance. I was a distinct failure with the cello. Eventually my parents sold the cello and bought a vacuum cleaner. The sound in our home improved. So that was out. I could write, and I still do. I wrote before I photographed and it is still meaningful. But it lacked action. Photography, for me, was writing in action. The great artist and illustrator Saul Steinberg once described himself as "a writer who draws." I think of myself as a writer who photographs. Images, for me, can be considered poems, short stories or essays. And I've always thought the best place for my photographs was inside books of my own creation. I was editor of my high school yearbook and editor of the 1967 Kentuckian and photographer for both. There isn't an aspect of book creation I don't enjoy, and there has always been a book in my life to dream about or work on.

Q: How did you find your way to National Geographic?

A: My parents, grandmother and brother were teachers. My mother taught Latin and French and was the school librarian. My father taught geography and a popular class called family living, the precursor to sociology, which he eventually taught. My grandmother was a beloved one-room school teacher at Knob School, near Sonora in Larue County, Ky. Education, in its many forms, was the culture of our family life. Travel trips, as an example, were a way to learn American history. So our vacations weren’t about camping or fishing. They were about going to Jamestown, Monticello and Mount Vernon. Also Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Mt. Rushmore. My brother and I were expected to learn about cultural history through direct contact with it. When I first went to National Geographic I thought I was the least qualified person to step through the doors. But because of my parents and the culture of continual learning they imposed on us, I later came to believe I was the most qualified person who ever worked there. After all, National Geographic's mission statement is about "the increase and diffusion of knowledge." That could have been the motto of our family's life.

I've had one job interview in my life. It was to become a summer intern at National Geographic in 1967. I had just finished editing the two-volume '67 Kentuckian and had sent the Geographic a box of black and white prints taken at UK. I also separately sent a box of original color transparencies (slides) made in the summer of 1965 on a UK/YMCA trip to Bogota, Colombia. This was the important part of my portfolio because the Geographic was all color photography. But the color originals never arrived. I'd used water soluble ink to address the box and the ink smeared and became unintelligible. The box never arrived. All I had on the table during my interview with the legendary Director of Photography Robert Gilka were the black and white prints from UK. I thought I was doomed. But I got the internship and it changed my life. Years later I asked Gilka if he'd hired me as an intern out of pity because my slides had been lost. "Hell no," he said. "We had no time for pity at National Geographic." "Why did you do it then?" He looked at me and bit off one word. "Potential."

Since that 1967 internship I've lived the National Geographic life. By that I mean I traveled on assignment for 33 years, ending in 2001. It was the right life for me. Assignments were long and involving, always lasting months and sometimes, it felt, years. Once I was in the field 14 straight months. I met my wife on assignment. She was hiking the length of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) in one summer. That's 2,600 miles from Mexico to Canada through the mighty mountains of the far west — the Sierras, Cascades and North Cascades. I was doing a book on the trail. At first I simply admired her, but that turned into affection and then love. After the first 500 miles the PCT isn't a test of strength. It is a test of character. She finished the trail that summer of 1974 and we were married in 1977. From then on we traveled on assignment, both of us together living the photographic life. Since 1978 we've lived in a central Virginia farmhouse once owned by a mill keeper. The house is in a setting that provides a haven from the rigors of travel.

Q: What was your favorite assignment?

A: I had a number of favorite assignments (besides the Pacific Crest Trail). I did the photographs for a book called "Still Waters White Waters," about canoeing in America (that was the 14-month epic). I did photographic biographies on Leo Tolstoy, Lewis Carroll, Charles M. Russell, Winslow Homer and James Madison. And books on the Appalachian Trail, the Civil War, the Mississippi River, and Lewis and Clark. The last two were with the well-known historian Stephen Ambrose. We became friends, which was one of the significant benefits of living this life and being in the field with writers.

I have favorite places and assignments. The island of Newfoundland, subject of my first assignment, is a place I think of fondly. For sheer majestic geography and sublime scale, nothing beats Alaska and the Yukon. For culture, Japan. And for all-around affection, Australia. It was foreign but familiar, great fun and good photography — all the things you could wish for on assignment. I did two Geographic cover stories as well as two books on Australia. It's the place, and the people, I think of most often.

Q: Have you ever found yourself in danger on a National Geographic assignment?

A: In a way danger is something I sought. Maybe I should say the edge of danger. I didn't want to injure or imperil myself, but I felt the most vital place to be was on the line between danger and beauty. As a person and as a photographer I was most alive walking that line. Too much beauty was boring. Too much danger was ... dangerous. But if you were willing to push the line of danger, it was often into a unique realm of beauty. An example was my effort in Australia to photograph a cyclone. It was an important element of life in the northwest of Australia. There is even a cyclone season called "The Wet," so the image was essential in expressing the story of life in the Outback. But I happened to be there during the driest "wet" of the century. So I went looking for a cyclone off the remote, empty coast. The pilot was young. I instructed him to fly along the dark, distinct edge of the cyclone. But the storm somehow overtook us. The downdraft nearly destroyed the small plane. An argument erupted about what to do — fly through the downdraft again to clear air space or further into the black storm toward land? I argued for clear air (and no certain landing spot), the pilot argued for land. He gestured toward land and said, "There!" We both looked "there." Just then a continuous sheet of forked lightning spread across the black sky. I shouted, "There!" and jerked my thumb to the now distant sliver of bright sky between the dark boiling clouds and sea. As I did so I couldn't help but see how unique and intensely beautiful the graphics and color of the scene was. I picked up my camera and began to photograph. It settled me to do so. But I also photographed because it was beautiful. In a dangerous way. The picture was published in the Geographic in 1990. Last week in Massachusetts I showed the image in a slide show. After the program a woman approached me, introduced herself as an artist and said, "That picture of the storm in Australia — from it I learned how to paint clouds. Thank you so much!"

Q: What brought you to the UK College of Education?

A: I was attracted to the UK College of Education because my parents wanted me to get a degree in education. I understood that. Teaching was our family culture and made such a fundamental contribution to our community. I'd seen that in how respected, even beloved, my parents and grandmother were. What they did mattered. My brother continued that family tradition. And, in a way, so have I. I’ve taught photography workshops for 30 years in the U.S. and abroad. Nominally the classes are about photography but the real thing I'm teaching is life, and about how photography is a positive way of "being in life." My parents taught that lesson, too. Whether the class was about French or geography (or photography) the real lessons from them were about learning itself, and its worth and constancy in life.

Q: Can you talk a little about your upcoming book project?

A: I'm now at work on an extensive publishing project titled "Sam Abell Library" (Radius Books, Santa Fe). It is to be a 16-book set of my life's work. Beginning this fall, it will be published in four annual installments of four matching boxes (slip cases) each containing four volumes. The four boxes will be themed: Box 1 is "The Photography of Places" with volumes on Newfoundland, Japan and Australia; Box 2 is "The Photography of Nature" with volumes on the Galapagos, Amazonia, Canoeing and The Long Trails; Box 3 is "The Photography of History" with volumes on Tolstoy, The Shakers, Charles M. Russell (Montana's traditional ranch life) and The Japanese Imperial Palace; and Box 4 is The Photography of Ideas and will contain volumes on Seeing Gardens, Portraits, and Black and White images. The 16th volume is called "Things — A Memoir." It will contain still-life images of those items in my life that have had a "life" and will be accompanied by relevant stories. The volume of black and white images will have work from my student years at UK and The Shakers volume will be extensively filled with images of Shakertown, not far from Lexington.

Working on this 16-book retrospective has allowed me to reflect on my life. The best lesson I was given is that all of life teaches, especially if we have that expectation.

MEDIA CONTACT: Jenny Wells, (859) 257-5343; Jenny.Wells@uky.edu