The Difference Maker

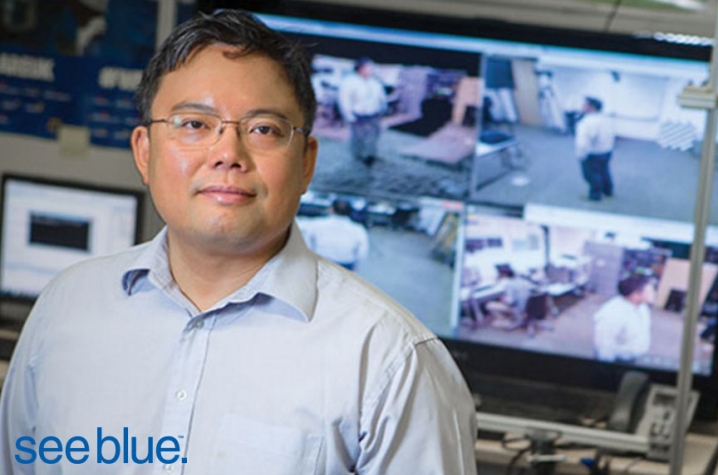

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Jan. 13, 2016) — Sen-Ching (Samson) Cheung is an associate professor in the University of Kentucky College of Engineering’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and a faculty member within the UK Center for Visualization and Virtual Environments. Like most professors, he is deeply involved in engineering research. For most of his academic career, his research has been in the area of multimedia information analysis.

“I enjoy solving problems and developing new theories, working on new technology and future products,” Cheung explains. “But something like video surveillance does not impact me personally. At the end of the day, I can leave my research in the lab.”

The distance between professional research and personal impact was shortened a several years ago when Cheung and his wife began to detect developmental delays with their young son. They noticed he avoided social contact and wouldn’t look anyone in the face. Not even his parents. Eventually, they had him tested; the diagnosis: autism spectrum disorder.

“Though we were disappointed about the diagnosis, we began taking our son to different therapies and reading about effective ways to help children with autism,” Cheung recalls.

Not only did Cheung immerse himself in the latest autism therapies, he also began applying his engineering background to a field of research he had never anticipated engaging. Working with UK researchers in the colleges of Education, Arts and Sciences, and Medicine, Cheung applied for and received a multi-year $800,000 grant from the National Science Foundation in 2012 to enhance the delivery of behavior therapy to individuals with autism and related disorders. In the three years since receiving the award, Cheung has not only developed therapy technologies for children, but also aids for the therapists and teachers who work with the children.

“Every autistic kid is different, which is why it is called autistic spectrum disorder,” Cheung says. “So I am trying to empower the parents and therapists by creating tools they can use and even customize for each child.”

The training mechanisms Cheung and his group have produced employ interactive gaming, wearable technology and even new approaches to surveillance. They also tap into well-known devices like Google Glass and Microsoft Kinect. Although each is in a different stage of development, Cheung says reception within the autism community has been positive.

“Whenever I go to an autism-related conference, I meet a lot of people and everyone has a story to tell. These are people who can really use some help. The recent diversification of my research has come from talking to people who say, ‘This is our problem; can you look at this and engineer something to help us?’ I get a lot of business cards and ideas from those kinds of conversations. Technology is playing a big part in autism therapy right now and it will play a bigger part in the future.”

Among his projects in the works, Cheung is excited about three that could make a substantial contribution to the crucial area of social skills training.

LittleHelper

As mentioned earlier, some individuals with autism possess behavior traits that make social communication difficult, such as lack of eye contact or inappropriate conversation volume. LittleHelper, which uses Google Glass, is designed to strengthen those social skills by giving immediate visual feedback in training sessions. Because wearing Google Glass is similar to wearing glasses, it has the advantage of being unobtrusive.

Using Google Glass’s camera and peripheral display, LittleHelper detects whether a user is looking at his or her conversation partner. If they are maintaining what is technically termed “eye gaze,” they will see a yellow happy face in the display. If they break eye gaze, feedback comes in the form of a frowning red face. Because many autistic children are visual learners, they are likely to turn back to their partner in order to once again see the happy face. A similar program offered by LittleHelper gives feedback of “SOFTER” or “LOUDER” on the display depending on the user’s speaking volume relative to the noise level in the room.

“That is why I call it ‘LittleHelper,’ clarifies Cheung. “It gives a little help in a few very important areas.”

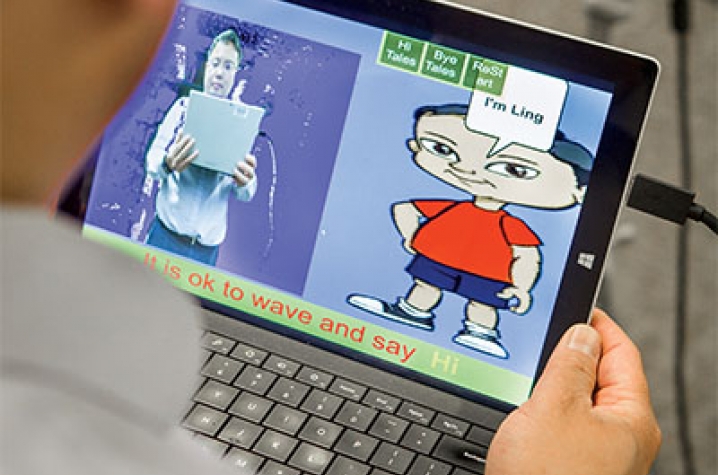

MEBook

MEBook is part story book, part interactive game that helps autistic kids learn the social skills of saying ‘hi’ and ‘bye.’ While such responses come almost automatically from most children, Cheung says they do not come naturally from children with autism.

Using a “social narrative,” MEBook allows the child to be the main character in a story and his or her face appears on the screen via a Microsoft Kinect. In the story, the child meets his friends and teachers, saying, ‘hi’ and ‘bye’ to them. After finishing the story, the child is ready for the game component. On the screen, cartoon friends appear, each saying, ‘Hi (child's name) ’ to the child. The goal is for him or her to wave and return the greeting or farewell. Gesture and sound recognition determines if there has been a successful response. If so, the game says, ‘Great job!’ and confetti showers from the top of the screen. According to Cheung, developing habits is the key to MEBook’s success.

“We ran three children on the spectrum through a clinical study around MEBook," Cheung said. "We measured social interaction prior to playing the game, as well as after, and we brought them back to see if they remembered what to do without playing the game. The kids really began to learn the skills. A couple of them went from not paying attention to anyone in the room to, weeks later, remembering to say hi and bye to other kids and adults in the room without even playing the game.”

Privacy Bubble

With the Privacy Bubble, Cheung has applied his extensive research in surveillance to classroom interactions in a novel way.

“Video cameras can make for a great instruction tool,” Cheung says. “When my son comes home from school, I ask him how it went and what he learned; but he is not able to tell me much. When I ask his teachers they might send me a checklist about his behavior or a list of the work he did, but I can’t replicate any of it because I didn’t see it. If the classroom had a video camera, it would be possible for them to extract the important parts and share that video with me. Then I would know the new things they taught, and I could do the same things at home. That would be very valuable for me.”

Almost as soon as Cheung describes his vision for cameras in the classroom, he quickly concedes the number one objection to it: privacy. In a classroom with multiple children, it would be nearly impossible to keep other kids off-camera during video-recorded training times. Hence, the Privacy Bubble. Utilizing a Kinect, Cheung’s surveillance expertise has enabled him to black out everything on the screen with the exception of the teacher and student. This “bubble” protects the privacy of other students while giving parents a helpful tool for staying abreast of what is going on in the classroom.

“Plus,” Cheung adds, “if I could see the teachers having trouble getting my son to do certain things, I would know if something we tried at home would be worth sharing with them.”

Cheung had the opportunity to demonstrate LittleHelper and MEBook at the International Meeting of Autism Research in Salt Lake City last May — a conference that features the world’s top researchers in the field of autism and showcases new technology aimed at improving autism spectrum disorder therapies. Cheung says the enthusiastic reception for both programs encourage him to stay the course.

“Academics are like kids in the sense that we really like to share things we think are cool," he says. "And when people share your joy in an area so personally important to you, it makes all the difference.”

MEDIA CONTACT: Whitney Harder, 859-323-2396, whitney.harder@uky.edu