UK is First in U.S. to Conduct Trial of Promising New Treatment Strategy for Parkinson's Disease

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Nov. 18, 2013) – A clinical trial being conducted at the University of Kentucky is investigating a new treatment strategy for Parkinson’s disease that, if successful, could drastically change future treatment of the disease and possibly halt or reverse brain degeneration. UK is the first in the U.S. to conduct the clinical trial.

Dr. Craig van Horne, associate professor of neurosurgery in the College of Medicine and principal investigator of the clinical trial, came to UK only two years ago, but he is already making significant contributions to research and patient care related to Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s is one of the most common neurological disorders, affecting around one million Americans and 10 million individuals worldwide. The disease is progressive and degenerative, wherein the death of brain cells causes an array of motor and non-motor symptoms, most recognizably tremor, rigidity, slow movement and unstable posture. Despite its prevalence, there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s disease, in part because its causes aren’t fully understood. Symptoms are initially managed through medication, but the medication loses efficacy over time.

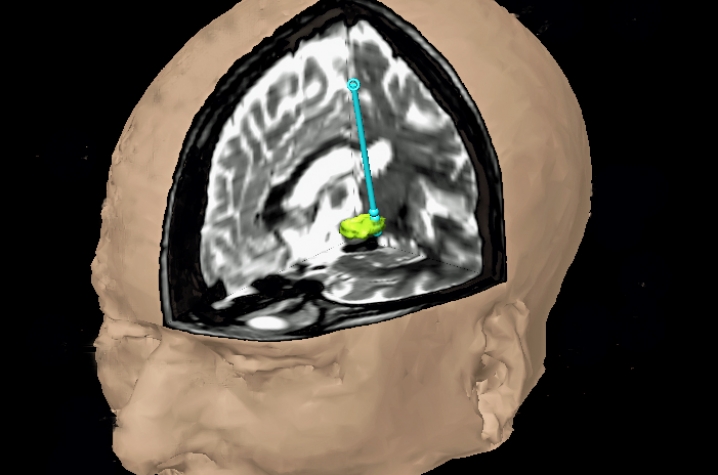

The next line of treatment is a surgical procedure called deep brain stimulation (DBS), which received approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002. DBS works like a “brain pacemaker” whereby electrodes are surgically implanted deep into the malfunctioning part of the brain where cells have died. The electrode then emits electrical impulses to regulate the brain’s abnormal impulses. For many patients with Parkinson’s disease, DBS can be a life-changing treatment that greatly improves quality of life by reducing their symptoms and their dependence on medication, which can have drastic side effects even as its efficacy decreases. But while DBS is effective in managing symptoms, it still does not change the course or outcome of the disease.

Supported by pilot program funding from the UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS), van Horne, with his team, is exploring an additional treatment option, and possibly a way to alter the course of the disease. They are conducting an innovative clinical trial that builds upon the established DBS procedure by supplementing it with a nerve graft of patients’ own peripheral nerves.

As any good neurosurgeon will tell you, the nerves in the brain do not regenerate when they are damaged. However, peripheral nerves—nerves outside of the brain and spinal cord—are able to regenerate by releasing a variety of neurotrophic factors, which are protein-like molecules that support growth and maintenance of neurons. Van Horne’s trial aims to leverage the regenerative capacity of peripheral nerves to allow the brain to heal itself. As part of the study, the patients donate a small piece of their peripheral nerve tissue from just above their ankle. The nerve tissue is obtained and implanted during DBS surgery, which means that the patients do not need an additional surgery for the grafting procedure and still receive all the benefits of the DBS therapy.

The potential clinical effects of the implants can then be tested by simply turning off the deep brain stimulator. The hope is that the neurotrophic factors of the peripheral nerve will stimulate regeneration in the parts of the brain that have been damaged by Parkinson’s disease.

While nerve transplantation isn’t novel, van Horne’s trial is the first of its kind to transplant peripheral nerve tissue into the brain in conjunction with DBS. It’s an idea he has been working towards for many years.

“I have been refining this concept for over 10 years,” he said. “I was looking at the research field, at what worked and even what didn’t work, and I was always thinking ‘Why wasn’t this research carried forward?’ People are looking for a magic bullet. But biology doesn’t work like that. And when I look at the regenerative capacity of other tissues in the body, I think “how can we take advantage of what nature has already figured out?’”

Van Horne received the competitive CCTS pilot award in July 2012 and was the only recipient in the history of the CCTS pilot program to receive two perfect scores from the internal review process, which is modeled on that of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). And within 18 months, he brought the trial from proposal to practice—light speed in the world of biomedical research and clinical trials. So far, five Parkinson’s patients have undergone the combined DBS-nerve graft procedure, out of six allotted spaces in the trial. These patients were already candidates for standard DBS and agreed to undergo the nerve graft after being informed of the risks and benefits.

“This is a beautiful example of how if you design a study correctly, it can go quickly,” said Dr. Greg Gerhardt, director of the Parkinson’s Disease Translational Research Center of Excellence and of the Center for Microelectrode Technology. Gerhardt assists van Horne during the DBS-nerve graft procedure.

Van Horne has been able to advance the trial so quickly in part because it did not require additional FDA approval, since it piggybacks on an approved procedure and uses a patient’s own nerve tissue.

“When I went to the FDA, they said there was nothing for them to regulate – there’s no additional surgery, no new device, and the patient is donating his or her own tissue,” he explained.

The use of the patient’s own tissue also eliminates the risk of the brain rejecting the implanted nerve, which in turn means that patients don’t need to take immunosuppressant drugs to reduce the chances of rejection. The nerve graft itself only adds about 30 minutes to the standard DBS procedure, so the increased risk to the patient is minimal.

Both the trial and the nerve graft are also remarkable in their low cost. Because the patients in the trial were already candidates for DBS, their insurance pays for all of the routine procedure (excluding the costs associated with the nerve graft). Furthermore, the nerve graft procedure uses existing technology and didn’t require development of expensive new tools.

As a Phase I trial, the primary objective is to establish safety and feasibility of both the initial procedure and the long-term effects. Patients in the trial are monitored through a 12-month period that follows motor performance and psychological scores and changes in how much medication they need to manage their symptoms.

The trial is ongoing, but preliminary data indicates no increased risk to the patients, all of whom have shown consistent improvement in symptoms. To illustrate, patients who undergo standard DBS are generally able to reduce their medication one month after the surgery. By comparison, all five patients who underwent the combined DBS-nerve graft procedure in van Horne’s trial were able to entirely go off the medication one month later, relying only on the DBS device to manage their symptoms. This is significant for patients because the DBS therapy provides more stable symptom management than the medications.

“What that data suggests is that maybe the graft combined with DBS can give patients more improvement so they don’t have to continue to use the medications, which have variable side effects,” said van Horne. “The patients can have more consistent “on” times—fewer ups and downs with their symptoms. They’re not fluctuating due to meds if they’re just using the [deep brain] stimulation.”

If successful, this procedure could significantly change the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and could have an impact on other neurodegenerative disorders as well. “This is something that could be very self-sufficient,” van Horne said. “It’s inexpensive, the patients are donating their own tissue, and the technology is very simple. It’s not genetic engineering, it’s not using fetal tissue, and we’re not trying to rebuild anything. And we can translate it to a number of different areas very inexpensively and with very little technology.”

Gerhardt also recognizes the long-term possibilities of the nerve graft to potentially change the course of the disease by using the regenerative capacities of the peripheral nerve to halt or reverse the progressive degeneration in the brain.

“With DBS, we can give patients something very special that improves the quality of their life, and we want to take it a step further,” Gerhardt said. “What we really want to do if this works is to put in the nerve graft before DBS is needed. First we have to show to the world and the FDA that this is a safe way to produce a therapy that is disease altering.”

For the immediate future, van Horne looks to what he calls “the adjacent possible”, the next possibilities that are immediately available. This could be repeating the trial with more patients, for example. Ultimately, the results of his study will be used to formulate an NIH proposal to optimize the procedure and continue to investigate the true clinical impact of the grafted tissue on clinical outcomes.

“It comes down to one question,” van Horne said. “What can we do for our patients to help prevent this disease from progressing?”

MEDIA CONTACT: Mallory Powell, mallory.powell@uky.edu