Pool Finds Evidence for Shared Governance in Ancient Mexico

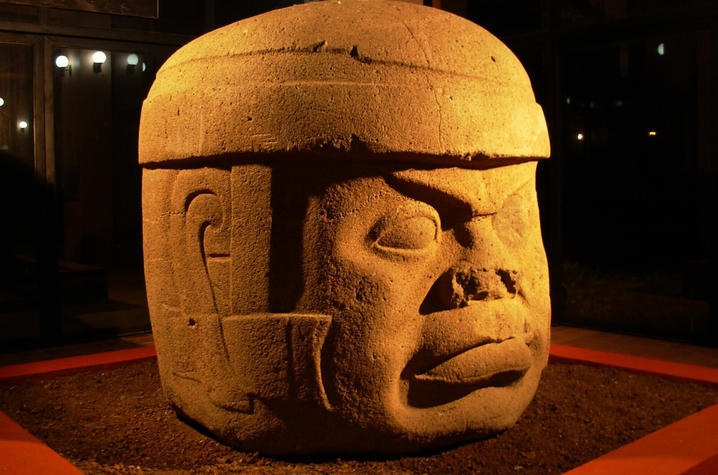

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 18, 2017) — For much of his career, University of Kentucky Professor of Anthropology Christopher Pool has been fascinated by Mexico’s ancient Olmec culture, with its gargantuan heads sculpted in stone and more mundane relics its artisans etched in ceramic.

An expert in Mesoamerica, the evolution of complex societies, political economy and cultural ecology and armed with a voracious curiosity, Pool began his fieldwork at the Olmec site of Tres Zapotes, Mexico, in 1995, some 140 years after a farmworker’s hoe first scraped the top of a buried stone head.

After numerous stone monuments were unearthed at Tres Zapotes, additional evidence of a highly sophisticated ancient culture was discovered. Archaeologists were lured away from Tres Zapotes by the discovery of the remains of several other ancient cities nearby and the tantalizing theory that the region was home to an early nation held together by a centralized monarchy.

“Tres Zapotes had been abandoned as an active site when I arrived; it had been nearly 20 years since the most recent archaeological excavation of the area,” said Pool.

Although huge prehistoric sculptures were fascinating, Pool was interested in learning something beyond the surface others saw and recorded. He wanted to learn how the citizens of Tres Zapotes lived their daily lives. How big was the city? How was it organized? Was there any connection with other ancient cities located nearby at San Lorenzo and La Venta? Did the nearby cities share in commerce, in politics, in beliefs?

Pool worked in Tres Zapotes six or seven years before he started “thinking differently” about the site. While he agreed with other experts that it appeared that most of the Olmec society had a strong, centralized rulership, he suspected Tres Zapotes was idiosyncratic, even unique among the other Olmec cities.

“Tres Zapotes is an unusually long-lived site, for one thing,” Pool said. “There is evidence that Tres Zapotes was a thriving community for nearly 2,000 years,” while the other Olmec cities with individualized rulership flourished as regional capitals for no more than 500 years or so.

“We now believe that the citizens of Tres Zapotes may have shared the power, not among each individual in that society — as in a democracy, but at least among several different factions within the city. It appears that Tres Zapotes may have survived centuries after other Olmec capitals collapsed because its cooperatve government allowed it to adjust to changing times, to survive,” said Pool.

Pool’s study of Tres Zapotes is chronicled in the March/April issue of Archaeology, a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America, and the March 17 issue of Science.