UK College of Health Sciences researchers find potential key to long-term knee health after injury

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Jan. 11, 2024) — A team of researchers at the University of Kentucky College of Health Sciences has found a potential way to help patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries return to their sports and daily activities faster.

The findings are from the team’s recent study published in Science Advances in November.

Researchers found evidence to improve recovery outcomes by targeting a specific protein in thigh muscles called growth differentiation factor 8 (GDF8). This protein helps control muscle growth, ensuring that muscles don’t grow too large.

“We hope to develop regenerative rehabilitation approaches to enhance patient recovery following knee injury,” said Chris Fry, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Athletic Training and Clinical Nutrition in the UK College of Health Sciences and the principal investigator of the study.

ACL injuries are common, affecting roughly 250,000 people yearly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A majority of people who suffer from ACL tears also develop posttraumatic osteoarthritis — a degenerative joint disease.

The goal of the study was to determine if an early identification of GDF8 predicted a longer-term lack of leg muscle size, strength and density of the bone surrounding the injured knee joint.

“Patients often sustain long-lasting strength deficits that can impact their ability to return to prior levels of activity and affect long-term joint health,” said Brian Noehren, Ph.D., associate dean for research in the UK College of Health Sciences and director of the human performance and biomotion laboratories. “Our findings provide exciting evidence to improve outcomes by targeting GDF8, although more work is needed to continue translating these findings to patients.”

Using a mouse model, researchers completed a variety of pre-clinical studies focused on ACL injury. Antibodies were administered to the mice, blocking the effects of GDF8. This was done to determine the efficacy of targeting GDF8 to rescue quadriceps muscle weakness, loss of bone density, and degradation of knee cartilage.

In this part of the study, researchers determined that inhibition of GDF8 prevented the loss of leg muscle, strength and size, which also protected against loss of bone density surrounding the knee.

There was also greater preservation of knee cartilage within the mice with GDF8 inhibition, meaning longer-term health of the knee joint may be possible.

Researchers then worked with patients who enrolled in the study. Participants had recently been diagnosed with an ACL injury and were scheduled for reconstructive surgery through UK HealthCare.

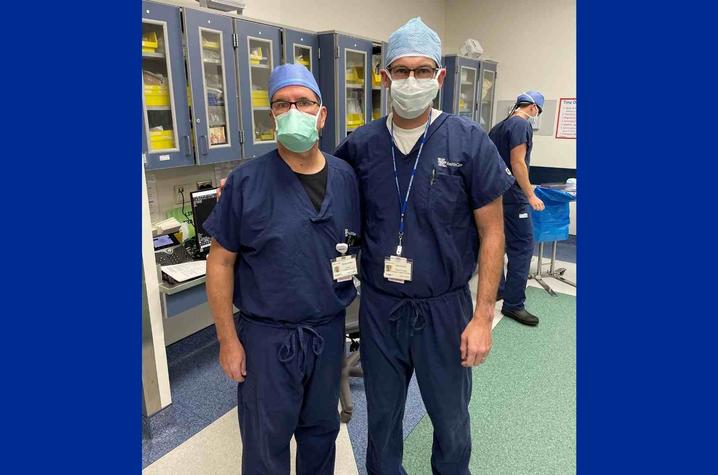

The participants completed an observational study with assessments of muscle biopsies, bone scans and strength and gait analysis led by Darren Johnson, M.D., and additional clinical expertise from Austin Stone, M.D., Ph.D., both in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine in the College of Medicine.

The team of researchers found that patients who had higher levels of GDF8 in their quadriceps muscle in their leg after ACL injury had the greatest decline in muscle size, strength and loss in bone density around the joint that remained for six months after reconstructive surgery.

“Our hope is to take this work and develop interventions that minimize the amount of muscle strength loss after a major injury allowing athletes and individuals to return to sport and work faster and safely,” said Fry. “With the results of our current study and the strength of our investigative team, we are optimally positioned to translate these findings to a clinical setting to support patients at UK HealthCare.”

This project brought together an interdisciplinary team of researchers and clinicians spanning orthopaedics, muscle biology, physical therapy, athletic training, nutrition and statistics in the colleges of Health Sciences, Engineering, Medicine and Arts and Sciences.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AR072061, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001998, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM121327. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.