UK Researchers Identify Macrophages as Key Factor for Regeneration in Mammals

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 16, 2017) — A team of University of Kentucky researchers has discovered that macrophages, a type of immune cell that clears debris at injury sites during normal wound healing and helps produce scar tissue, are required for complex tissue regeneration in mammals. Their findings, published today in eLife, shed light on how immune cells might be harnessed to someday help stimulate tissue regeneration in humans.

“With few examples to study, we know very little about how regeneration works in mammals; most of what we know about organ regeneration comes from studying invertebrates or from research in amphibians and fish,” said Ashley Seifert, senior author of the study and assistant professor of biology in the UK College of Arts and Sciences. “If we want to apply what we learn from basic regenerative biology to humans, it would be helpful to understand what cell types and molecules regulate regeneration in a mammal where it occurs naturally.”

Scientists have been trying to learn for years why some animals, like salamanders and zebrafish, are able to regrow body parts following injury, while others — like humans — can only produce scar tissue in response. Seifert’s lab learned nearly eight years ago that African spiny mice are one of the few mammalian models capable of complex tissue regeneration, making them particularly fascinating subjects. But what remained unclear was exactly how an identical injury in spiny mice and non-regenerating lab mice could produce dramatically different healing responses.

Seifert and his colleagues decided to investigate how the inflammatory environment might differ between the regenerative response observed in spiny mice compared to the typical scarring response observed in lab mice. Although white blood cell profiles were the same in uninjured animals from both species, injury elicited different local responses.

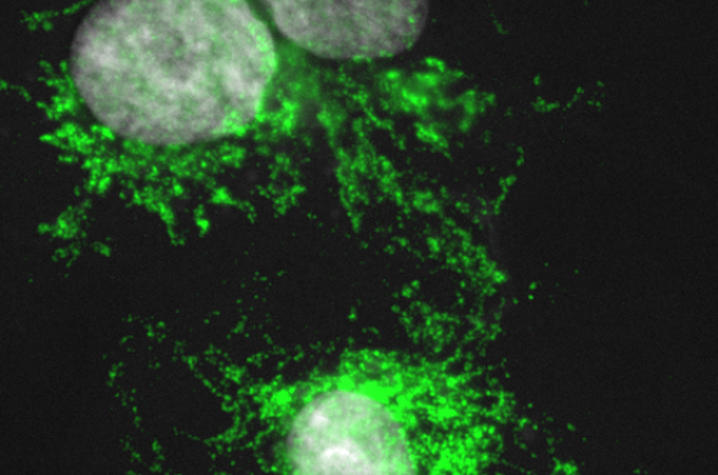

“We asked whether inflammatory cells positively or negatively regulate tissue regeneration in spiny mice,” said Jennifer Simkin, lead author of the paper and postdoctoral scholar in biology. “Comparing spiny mice to common house mice, we discovered that subtypes of macrophages active during regeneration are different than those active during scarring.”

Using the African spiny mice, the researchers depleted macrophages in the ear pinna and found these cells were required to initiate a regenerative response to injury. When they allowed macrophages to re-invade the wound site, regeneration occurred. When the team looked at different types of macrophages in healing tissue they found that a pro-inflammatory type of macrophage was highly abundant during scarring, but very rare during regeneration.

“There is growing appreciation that macrophages can adopt both regenerative and pathological functions,” said John Gensel, assistant professor of physiology in the UK College of Medicine and the Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center. “Our findings imply that macrophage activation in our model favors regeneration. The next step is to identify the components of macrophage activation that are necessary for regeneration. Since we are actively developing clinically feasible therapies that selectively activate macrophages, identifying targetable components of macrophage activation opens new areas of discovery with real potential for improving tissue regeneration in humans.”

The team’s results demonstrate an essential role for inflammatory cells to regulate a regenerative response. The next step is to explore these different types of macrophages and how the local tissue environment alters which types are present in response to injury. The hope is that studying these cellular mechanisms will lead to novel clinical approaches to restore damaged tissue in humans.

Gensel, Seifert and Simkin, along with postdoctoral scholar Thomas Gawriluk, are co-authors on the study. The paper can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24623.