A commonwealth of collaboration: The big fight to save a little heart

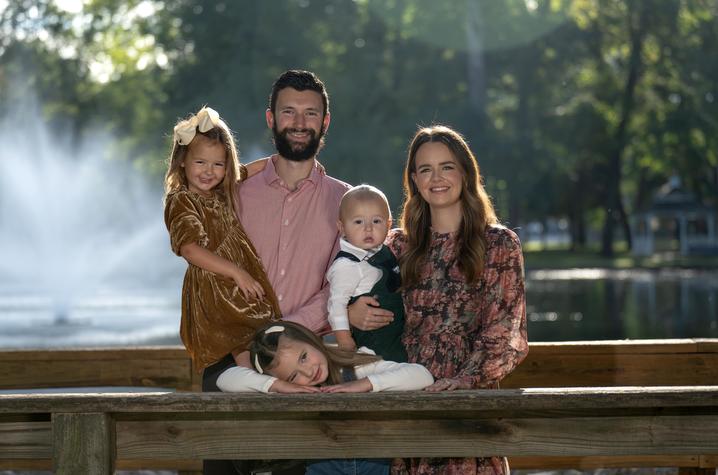

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Oct. 22, 2025) — Donald and Sarah Damron’s third baby was full of surprises.

As they prepared to give their two girls a younger sibling, they opted not to find out the gender, instead saving that excitement for the day of the baby’s birth. Little did they know that would not be the biggest surprise of the day.

In the 39th week of an uneventful pregnancy, Donald and Sarah went to UK King’s Daughters in Ashland for a scheduled induction. Their home is in Grayson, not far from Ashland, and the staff and providers at King’s Daughters are the Damrons’ friends and colleagues. Donald is the pediatric practice manager at King’s Daughters and Sarah is an ICU nurse at nearby Marshall University Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia.

In addition to being seasoned parents of two little girls, their work in the medical field gave them an edge when it came to preparing for a baby. They scrutinized all prenatal scans, tests and lab results; everything indicated their baby was perfectly healthy and meeting all growth and development milestones.

On Oct. 29, 2024, Donald and Sarah met their baby; their first son, whom they named Reid. When baby Reid was placed on Sarah’s chest for the precious ritual of skin-to-skin contact, both parents felt overcome with joy. However, that joy was tempered seconds later when it was apparent that something was terribly wrong.

“We were super excited for about 30 seconds that we were having our first boy,” said Sarah. “But his skin was really blue — that’s the first thing we noticed. And he had a really weak cry.”

The nurse measured Reid’s oxygen levels. A healthy newborn’s levels are typically 95-100%.

Reid’s was 30%.

Within minutes, baby Reid was put on a ventilator and taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Because of the common nature of the disease—and Reid’s initial presentation—persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) was suspected. PPHN is a condition in which a baby’s pulmonary arteries don’t open enough to let oxygenated blood circulate to the brain and other organs.

“Our girls were home wearing their ‘big sister’ shirts, waiting to find out if they were going to have a brother or sister, and then the next few hours of not even knowing if we’re going to have a baby,” said Donald. “It was really traumatizing. We were just kind of preparing ourselves, trying to do the best we could, not knowing if he was going to make it, which is really hard.”

The NICU staff worked to stabilize Reid, telling Donald and Sarah that the diagnosis wasn’t confirmed. He needed to be transferred to Kentucky Children’s Hospital (KCH), but they weren’t sure if Reid was stable enough to make the trip. His oxygen levels dropped to 19%. When Reid’s condition continued to worsen, an echocardiogram revealed a much rarer condition, and the need to transfer him became much more urgent.

‘It was a roller coaster’

Dextro-transposition of the great arteries is a rare congenital heart defect; approximately 900 babies in the United States are born with it each year. In a healthy heart, the pulmonary artery carries blood from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen. From there, the blood flows back to the heart, where the aorta carries the oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. In Reid’s heart, the pulmonary artery and the aorta were switched; instead of pumping the oxygen-poor blood to the lungs, the blood went back out to the body through the aorta. What little oxygenated blood Reid had coming from his lungs was going through the heart and back to the lungs.

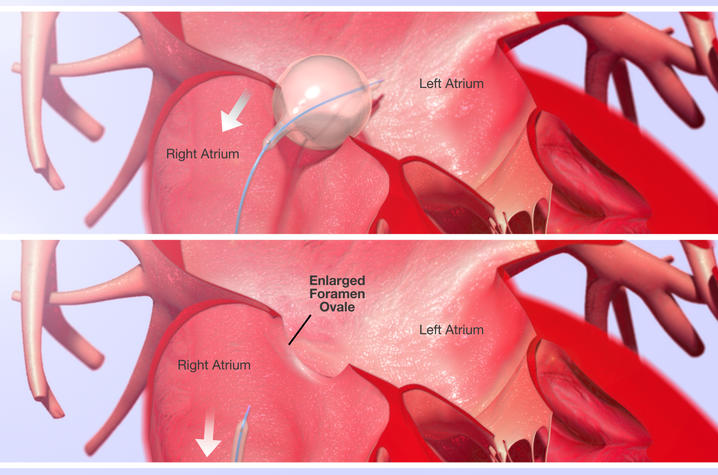

The only thing keeping Reid alive was a tiny hole in his heart. Babies are born with a hole in the wall between the two upper chambers of the heart, called the left and right atria, that usually closes on its own shortly after birth. It was through this hole that a small amount of oxygenated blood was making its way out of the heart and to the rest of Reid’s body.

Five hours after his birth, and with his oxygen levels teetering between 40% and 50%, little Reid was picked up by the Kentucky Kids Crew — a team of critical care providers specially trained in emergency transport — and flown to KCH in Lexington. Neither Donald nor Sarah could fly with him in the helicopter, but they felt a modicum of relief knowing he was in safe hands. Upon arrival, Reid was whisked straight into the heart catheterization lab by pediatric interventional cardiologist Jess Randall, M.D., where he and his team performed a delicate procedure that has a less-than-delicate description.

“Reid went straight from the helipad to the cath lab with need for an emergent procedure to tear a hole in his heart,” said Randall. The procedure, called a balloon atrial septostomy, involves accessing the chambers of Reid’s heart through a vein in his leg. A catheter is directed up and across the membrane separating the right and left atria, where a balloon was then inflated on the left side of his heart and then rapidly pulled back into the right atrium. This movement tears the membrane that separates the two chambers, allowing the mixing of high and low-oxygen blood and maintain a circulation until Reid was stable enough for the major surgery to correct the position of his heart’s blood vessels.

Back at King’s Daughters, Sarah and Donald were updated about Reid’s condition. Sarah experienced significant bleeding during delivery and had to stay behind while Donald raced to Lexington.

“I had just given birth, and off went my newborn baby,” Sarah said. “There were a lot of unknowns about what his life would look like, or if he would even still be here the next day.”

For Donald, the 119-mile drive from Ashland to Lexington was a blur; in a matter of hours, he and his wife had fallen from the heights of joy to the depths of anguish. He remembers arriving late at night at a near-empty hospital and how alone he felt as he made his way to the registration desk. KCH is located within UK HealthCare’s Albert B. Chandler Hospital, a maze of connected buildings that occupy several city blocks. It’s easy to feel lost in a place like that, but Donald focused on his singular mission — finding his son. A greeter at the KCH registration desk showed Donald to a room and made sure he felt comfortable. Shortly after, he met Randall and nurse practitioner Emily Walker.

“Those two specifically, I’ll never forget them because of the way they treated me and took care of our family,” said Donald. “Not just from that first moment, but for our entire stay. Emily relayed to us very well everything that was going on and provided emotional support.”

Sarah echoes that sentiment.

“I was at King’s Daughters by myself, and Dr. Randall and Emily both called me on my cell — even though they knew I was communicating with Donald,” she said. “They both called me personally and answered my questions. I thought that was really nice.”

The emergency catheter procedure was just a quick fix; Reid still faced the complex, open-heart surgery to switch the connections of his pulmonary artery and aorta. Both Sarah and Donald are medical professionals; even though they admit that their knowledge of congenital heart defects was limited, they knew Reid’s condition was treatable. But their training instinctively informed them of all the ways it could go wrong.

“It was just a situation where you really had no option but to just trust what they told you they were going to do and how that it works because otherwise, we knew he wasn’t going to live,” said Sarah.

“It was a roller coaster,” said Donald. “I remember being completely in the dark, not knowing what was going on, then figuring out he had a heart defect. Then for just a moment, despite how terrible everything was, we were happy because we knew it was treatable, but then going back to being really scared because we knew what was going on and we knew it was going to be really serious.”

***

‘He was going into heart failure’

Sarah was discharged from King’s Daughters the next day and joined Donald in Lexington. Initially, the plan was for Reid to have his major operation a week after the cath procedure. But a bout with neonatal pneumonia derailed those plans, and the surgery was put off for another week. At that point, Reid couldn’t wait any longer.

“He was really needing surgery,” said Sarah. “His heart was working overtime. He was going into heart failure. He was so swollen, he couldn’t open his eyes a lot of days. They were giving him a lot of diuretics. He was intubated when he first got there, then extubated, then re-intubated and extubated again. It was a very rocky start and a really, really stressful time.”

There was talk of transferring Reid again, this time to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. KCH and Cincinnati Children’s collaborate on the Joint Pediatric and Congenital Heart Care Program, bringing together cardiac experts from both hospitals to create one of the top pediatric cardiology programs in the country. While Donald and Sarah were prepared to go anywhere to get Reid the help he needed, Cincinnati was even farther from home and their support system in Grayson. Ultimately, pediatric cardiac surgeon Awais Ashfaq, M.D., came from Cincinnati to join KCH chief of pediatric cardiothoracic surgery Carl L. Backer, M.D., and cardiac surgeon William J. Wallen, M.D., for the eight-hour surgery.

“The arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries (TGA) is a complex neonatal cardiac procedure that has only been widely performed since the early 1990s,” said Backer. “UK sees one to two babies per year with this diagnosis. However, our partners in the Joint Heart Program, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, has a group of surgeons that perform 10-15 arterial switch operations per year on babies with TGA.”

To correct the positions of the pulmonary artery and the aorta, little Reid was placed on a cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) machine, a device that temporarily takes over the functions of the heart and lungs during surgery. While the machine circulated oxygenated blood through his body, the surgeons detached the pulmonary artery and aorta from his heart, and reattached them in the correct orientation. The coronary arteries, the small vessels that send blood to the heart muscle, were also moved and reattached to the aorta. The hole between the upper chambers from his emergency procedure was closed as well. Once the switches were made, Reid was removed from the bypass machine. His heart was restarted; the strong beat was the most beautiful music to his parents’ ears.

“Everything was good — really, couldn’t have looked better,” said Sarah. “He didn’t have any unanticipated blood loss or arrhythmia. They were able to close up his chest. Any of the complications they prepared us for, we were able to avoid. So, after everything we went through for those two weeks prior, we were very, very, thankful that it went as smoothly as it could.”

***

‘He’s the happiest little baby’

The morning after his surgery, Reid was taken off the ventilator. Sarah and Donald braced themselves for a myriad of post-surgical complications — some new wrench to be thrown into little Reid’s already harrowing journey.

But none came.

“The next morning, he was just eating a bottle,” said Sarah. “Just doing everything so amazingly — everyone was so impressed with him. But also, a little scared of him because he had been so sick. We were like, ‘Do we trust you? Do we trust that you’re actually doing this well?’ But he did. He did amazing.”

The Damon’s rented a house near the hospital and brought their daughters from Ashland so they could meet their brother. At night, Donald stayed at the rental house with the girls while Sarah stayed with Reid in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. During their long hospital stay, Donald and Sarah became close with everyone on Reid’s care team.

“Dr. Randall came by almost every day to check in on us and say hi,” said Donald. “Three nurses we had — Emily, Claire and Cam — they took wonderful care of us. They’d spend extra time with us and just talk with Sarah. They served as friends when we really needed them.”

At 25 days old, after experiencing more medical interventions than most people will in their entire lives, Reid went home to Grayson with his family. His heart and incisions were still healing and he required quite a few medications. Donald and Sarah were especially worried about Reid’s big sisters, Daely, 5, and Rosie, 3, who might be over-eager to hold and play with their little brother. But like everything else in Reid’s recovery, that scenario never materialized.

“The girls wanted to hold him,” said Sarah. “And we were scared to death after everything we just went through. With a newborn baby, you want to protect him from everything, and then you have a newborn who just had open heart surgery, you want to double protect him. But they were really good with him. We did have to coach them a little bit, but they kind of knew, deep down, how they needed to be with him.”

Reid is approaching his first birthday. He’s had to make a few trips back to Lexington for follow up appointments with Randall, but soon will have his routine checkups at King’s Daughters; KCH cardiologists regularly meet with heart patients like Reid to save their families the trip to Lexington.

“It’s been great,” said Sarah. “To know that if we need something, we don’t always have to go all the way to Lexington and have the option to stay at King’s Daughters and be closer to home.”

Other than needing to check in with a congenital heart specialist regularly for the rest of his life and a small chance of another procedure in the future, Reid has no restrictions or limitations.

“Dr. Randall loves to tell us now that he’s a normal, boring baby,” said Sarah. “He’s just living life, doing normal baby things.”

With Reid’s dramatic journey behind them, the Damrons are only looking forward. As a family of avid hikers, they can’t wait to take Reid on their annual trek in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, as well as check more national parks off their list — as a family of five.

And they know Reid will be happy just to be along for the ride.

“Anyone who’s been around him says he’s the happiest little baby they’ve ever seen,” said Donald. “He’s just happy to be alive.”

UK HealthCare is the hospitals and clinics of the University of Kentucky. But it is so much more. It is more than 10,000 dedicated health care professionals committed to providing advanced subspecialty care for the most critically injured and ill patients from the Commonwealth and beyond. It also is the home of the state’s only National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, a Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit that cares for the tiniest and sickest newborns and the region’s only Level 1 trauma center.

As an academic research institution, we are continuously pursuing the next generation of cures, treatments, protocols and policies. Our discoveries have the potential to change what’s medically possible within our lifetimes. Our educators and thought leaders are transforming the health care landscape as our six health professions colleges teach the next generation of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other health care professionals, spreading the highest standards of care. UK HealthCare is the power of advanced medicine committed to creating a healthier Kentucky, now and for generations to come.