UK Health Sciences Creates Simulation to Prepare Future Physical Therapists for ICU Care

LEXINGTON, Ky. (March 9, 2021) — Mrs. Smith lies back on a bed in the intensive care unit (ICU), eyes closed, her body connected to lines and tubes from a variety of machines: supplemental oxygen, a left brachial artery line, catheter, chest tube, a Jackson Pratt drain and a right brachial PICC line. This once-active middle-aged woman has fought a hard battle with pneumonia and longs to return to her favorite activities: running, hiking, walking her dog.

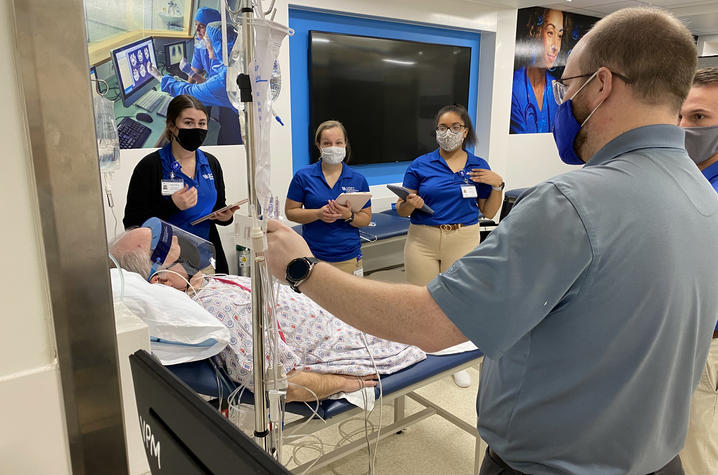

A group of physical therapists comes into the room with an indeterminate goal: to see how much physical activity Mrs. Smith can work through today.

Except Mrs. Smith isn’t actually a real patient, and this isn’t a real ICU. “Mrs. Smith” is an actor from the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, and she’s set up in a faux ICU room inside of UK HealthCare’s Simulation Center. Today, for the first time, a group of first-year physical therapy students from the UK College of Health Sciences will learn how to work with acutely ill patients whose mobility may be severely limited by their illness and by the machinery that’s helping keep them alive.

“The idea is to start to introduce them to an ICU setting, and to introduce them to the idea of interdisciplinary communication, work and roles,” said Angie Henning, UK HealthCare physical therapist and adjunct faculty with the UK College of Health Sciences. “We’re showing them the ways you modify, how you manipulate the patients’ lines and tubes to perform interventions. We’re showing them that even though there’s a lot of things going on, these people can still exercise.”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, physical therapy students’ first real experience in an acute care setting came from an observation. Groups of 2-3 students would be invited to shadow a physical therapist in a UK HealthCare ICU for an hour, watching how the therapist worked with individual patients. This was supplemented with real-life educational patient stories from UK HealthCare therapists like Henning, along with a simulated acute care bedside – with a mannequin – set up inside a Wethington lab for students to review at their leisure.

With COVID-19 precautions in place, an ICU observation wasn’t a viable option for this year’s students. UK College of Health Sciences faculty Kirby Mayer, assistant professor of physical therapy, and Deborah Kelly, associate professor of physical therapy, devised the idea of a real-life simulation, complete with an actual “patient.”

“The Sim Center has been fabulous working with us because we wanted to create this unique experience where the students will be able to put their hands on a critically ill ‘patient’ and start to provide physical therapy treatment,” Mayer said. “They can learn how to manage lines and tubes and vital signs while getting patients who are really sick up and moving.”

During the simulations, Mayer and Henning lead small groups of physical therapy students through their respective cases. Henning oversees Mrs. Smith, and prompts the students to begin by introducing themselves and assessing the patient’s cognition through a series of questions about her name, date and birthday. From there, they ask her to perform a simple series of tasks – squeezing a hand, lifting the arms and legs – before helping her sit up. Even rising to a seated position takes special coordination, as the students carefully lift the lines and tubes connected to Mrs. Smith and roll one of her IV stands over to the opposite side of the bed.

All the while, they’re carefully monitoring her telemetry: blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen. But they’re also watching her closely, looking for changes in demeanor, shaky muscles, difficulty catching her breath. Each change in Mrs. Smith’s numbers or symptoms prompts a new question for the students from Henning: “Physiologically, what does that indicate?” “Based on what you’ve seen, what comes next?”

Sitting on the edge of the bed, with one student behind her for support and one in front watching her legs, the group has Mrs. Smith perform a seated march: lifting up one knee and then the other. On the faux monitor, her blood oxygen drops.

“What now?” asks Henning. The students ask Mrs. Smith to sit up a little taller – she had begun to slouch – and take some deep breaths. Her oxygen levels return to normal, and her therapy resumes.

It’s this constant monitoring that can be a little overwhelming for therapists who have only had experience working in outpatient physical therapy, Henning says.

“In an outpatient setting, patients are highly mobile, for the most part,” Henning said. “But going to the ICU, you have the telemetry and you are monitoring so many things – heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation. But you’re also just looking at the patient’s signs and symptoms, too. If you’re a new therapist or coming from a different setting, just the number of lines and the amount of monitoring can be overwhelming.”

The students’ next goal is to get Mrs. Smith to stand, a task that requires the coordinated effort of four people: one person on each side to assist her as she rises, one person to hold the walker and some tubing out of the way, and one to hold the large box for Mrs. Smith’s chest tube drain so it doesn’t become unhooked.

Many of these simple movements are ones we take for granted – sitting up, standing, walking – but for patients who have been critically ill, they are monumental achievements. They’re also stepping stones to help the patients improve their overall health.

“We start with the basics, like sitting on the side of the bed,” Mayer said. “If you can get someone upright, the heart and lungs work better, so we’re helping with some of the healing and recovery.”

Danville native Gabby Imfeld was one of the five first-year physical therapy students who aided Mrs. Smith during this session. Imfeld had some prior experience with an acute care setting, having shadowed a physical therapist at Ephraim McDowell Hospital for three weeks in 2019. Since that therapist covered multiple floors of the hospital, Imfeld was able to see a distinct difference between the needs of an orthopedic patient versus a severely ill ICU patient.

“Some of the patients we saw would be able to get out of bed, do active things, and come to our gym,” Imfeld said. “The ICU patients were obviously a lot sicker… even some of the patients who hadn’t been there very long, you could just see how much deterioration had already happened. We were still able to do some minimal things with [the ICU patients], but there were definitely times where we would go in and just be able to do a passive range of motion or maybe sit up.”

Because of shifts in the physical therapy curriculum due to COVID-19, this group of students is experiencing the acute care piece of the program even earlier than they would have prior to the pandemic. In total, 48 physical therapy students from Lexington completed the acute care simulation in early February; due to severe winter weather, the 18 students currently enrolled in UK’s physical therapy program at the Center of Excellence in Rural Health in Hazard will be rescheduling their simulation for later this spring or summer.

But even with less than a year of physical therapy school under her belt, Imfeld says what she’s learned at UK so far has already helped her gain a greater understanding of how to care for critically ill patients.

“I think the Sim experience was especially cool because when I had shadowed with the ICU before, I didn’t know what was going on,” Imfeld said. “So now I know, ‘Oh, these are what these lines and tubes are for, and this is the goal that the therapist is trying to reach.’ It makes a lot more sense, in retrospect.”

While physical therapy in the acute care setting presents extra challenges in comparison to most outpatient therapy, Henning notes that it’s rewarding work. The five students helping Mrs. Smith seem to agree, as all five note that they would be interested in a career as an ICU therapist after they graduate.

Physical Therapy on the COVID-19 Floor

Henning spends much of her time in UK HealthCare’s cardiovascular unit and has worked extensively with both pre- and post-transplant patients in the past. In that area, a patient’s strength and their ability to perform these simple tasks could mean the difference between being listed for transplant or not, and these factors play a significant part in how quickly patients may recover after a surgery. Across UK HealthCare, physical therapists in acute care have similar goals: aiding patients both before and after major procedures.

And in the past year, physical therapists across UK HealthCare’s ICUs have taken shifts on UK’s COVID-19 floor, which presented an entirely new set of challenges. Many of UK’s COVID-19 patients are sedated and on ventilators, and in these cases, Henning says the focus changes. Therapists may passively work a patient’s joints through a range of motion to keep them mobile. If the patient can do a “sedation vacation” – where sedation is lightened as the lungs improved – a therapist will be on standby to see if the patient can respond to voices or follow commands as they begin to wake up.

And even if COVID-19 patients are awake and mobile, they might spend many weeks in an ICU room, possibly in isolation if they continue to test positive for the virus. Therapists may ask patients to perform some simple exercises in bed and find ways to work the accessory muscles in the trunk of the body – including the diaphragm – to help the lungs expand more. For patients who are further along in recovery but still in isolation, therapists may recommend simple bodyweight exercises from the GetWellNetwork, available on all the televisions inside UK HealthCare patient rooms.

“Every day we spend in bed, we lose about 3% of our muscle mass,” Henning said. “So the GetWellNetwork has exercises for patients who are high level, and they’re typical exercises that are more power-driven, like sit-to-stands, heel raises, wall push-ups. We’re trying to get the most bang for their buck.”

Ultimately, it takes a village to heal COVID-19 patients – physicians, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, and more, all working and communicating together. Henning originally came to an ICU setting more than eight years ago because she says she enjoyed the challenges that come with the territory. This year, those challenges are even more pronounced, but she keeps her focus on one thing: the patients.

“We’ve seen a lot of really, really sick people, even young people in their 40s and 50s, and unfortunately a lot of bad outcomes,” Henning said. “So you hold on to the positives, and you see that you’re really helping people.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.