‘We both come out winners’ — patient highlights UK/Louisville Gift of Life Challenge

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Dec. 7, 2022) — An avid soccer fan, Charles “Chip” Hunter was planning to wake up early on the morning of Feb. 26 to watch his favorite English Premier League team, Tottenham. But 30 minutes before his alarm was set to go off, his wife, Melanie, got a phone call and urgently nudged him awake.

“I was like, ‘I'm getting up at 7 a.m. to watch my team play,’” he said. “Give me thirty more minutes.”

“That was the hospital,” Melanie said. “They have a kidney for you.”

He shot out of bed. Just hours later, Chip underwent the kidney transplant he had spent more than five years waiting for.

*****

Chip has been a member of the UK family for 11 years, working various jobs around the university before settling into his current position in the College of Medicine. In 2011, he decided to pursue his master’s in health administration. Between his job, schoolwork and his internship, he felt fatigued, but attributed it to his workload.

“I was in the last year of my MHA program,” said Chip. “I was working here from 5 a.m., going to class, doing my internship. I was just feeling run down. But I thought it was just because I was doing too much. I found out after I graduated a few months later that my kidneys were functioning probably at about 8-10%.”

Chip always knew it was a matter of time before his kidneys would fail. In 2008, he, like his father before him, was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a condition in which cysts grow all over the kidneys and kill the filters.

“Not all patients with PKD develop kidney failure, and the likelihood of requiring dialysis or kidney transplant is estimated to be near 50% of PKD patients by age 70,” said Jonathan C. Webb, M.D., Hunter’s nephrologist at UK.

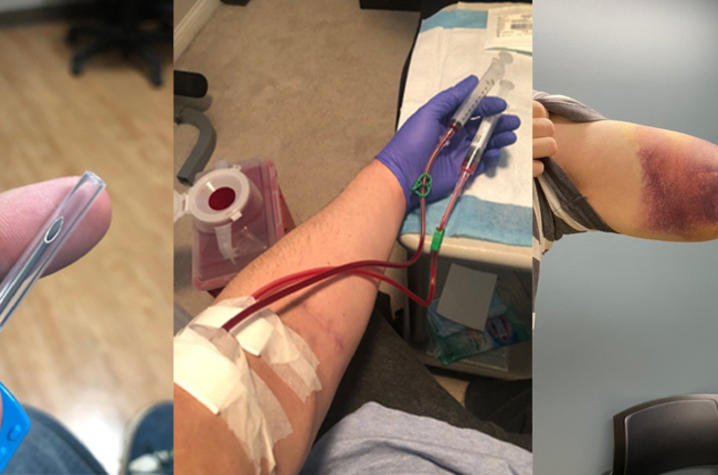

His doctors quickly started him on dialysis. He started with peritoneal dialysis, a process to remove waste products from the blood when the kidneys can no longer do so. He did this for eight hours at a time, five nights a week. Eventually he switched over to doing hemodialysis at home.

“I would work here from 8-4:30, get home by 5 p.m., set my machine up for an hour, do dialysis till about 10:30 at night and go to bed and do it all over again the next day,” he said. “I got used to it. I always felt bad for my wife because she didn't sign up for this. I mean, before we got married, I told her there's a possibility of this. But we didn't think it would hit until I was about 50 years old.”

These treatments took up so much of his time, and his whole world revolved around them for more than five years. PKD had completely ruled his life, as well as Melanie’s, who acted as his caregiver during this hard time.

“It takes up your whole life,” he said. “You don't really have any free time. On dialysis, you have to do it five nights a week for four to five hours, so you have to be home at a certain time. You can't go after work. You plan your weekends around it.”

Dialysis only slows the progression of the kidney failure. While people can survive for years on dialysis, Chip will be the first to tell you it’s a hard way to live. So when Melanie got the call about his transplant, he was elated, not just for himself.

“I think I was happier for her than myself when I got my transplant,” said Chip.

When Chip and Melanie arrived at the University of Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Hospital, he had one joking question for his care team:

“Can you wait until after the UK/Arkansas game?”

*****

Nine months later, Chip feels like a new man.

“Before, I was about 380 pounds,” he said. “When I started dialysis, I got down to just about 320, 315. And then about, two years ago, I decided I need to lose weight. I'm so glad I did. I’m down to 260. I can’t imagine trying to recover from transplant surgery at 380 pounds.”

Chip’s kidney transplant changed his life and gave him so much more freedom. He is now able to enjoy things he was unable to do for so many years.

“I can go for long walks, play with the dogs, go to the movies, go out to dinner, even though I really shouldn't because it's loaded with sodium,” Chip said. “I can do yard work, finally. But just going on trips — I remember we'd go visit my mom in Atlanta and half of the car is full of supplies. Even though I take a lot of medicines now, but I'd rather take 20 minutes to fill my medicine for the week than spend 25 hours a week on the machine.”

Chip doesn’t know anything about his donor. While he and his family tried for years to find a compatible living donor, ultimately his kidney came from someone who had joined the Kentucky Organ Donor Registry. Even though he hasn’t yet found the words he wants to say to his donor’s family, he wants them to know how grateful he is ... and how sorry.

“I haven't been able to write a letter,” he said. “But I went through that guilt. You want the live donor. But that wasn’t going to happen. I was just glad that they were a donor. I felt guilty, thinking about their family. It's been nine months for me. But it's also been nine months for them.”

*****

More than 1,000 Kentucky residents are waiting to receive lifesaving hearts, livers, lungs, kidneys and other organs. Organ donors offer recipients a second chance at life, but the need for donations is much greater than the number available.

The University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville are keeping their rivalry and competitive spirit alive while inspiring thousands of people to join the Kentucky Organ Donor Registry with the 21st year of the Gift of Life College Challenge. Though the challenge deadline has passed, the need for donors is still dire for people like Chip.

“This may sound weird to some, but even though I had a life-altering chronic disease, I was blessed with one where I could do a procedure that could mitigate my disease and keep me alive,” Chip said. “On top of that, I was able to work and live a relatively normal life, not everyone has that blessing.”

This year's winner of the Gift of Life College Challenge will be announced at the UK/Louisville basketball game on Saturday, Dec. 31. While the challenge is a friendly competition, Chip points out that ultimately, everyone wins.

“Whether it be a heart, liver, lung, kidney there are nearly 1,000 Kentuckians waiting on a lifesaving organ that will make their quality of life so much better,” he said. “This is one instant where beating Louisville would be great — but no matter what, we both come out winners.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.