UK Study Examines Impact of B Cells on Stroke Recovery

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 14, 2020) — New University of Kentucky research shows that the immune system may target other remote areas of the brain to improve recovery after a stroke.

The study in mice, published in PNAS by researchers from UK’s College of Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and University of Pennsylvania reveals that after a stroke, B cells migrate to remote regions of the brain that are known to generate new neuronal cells as well as regulate cognitive and motor functions.

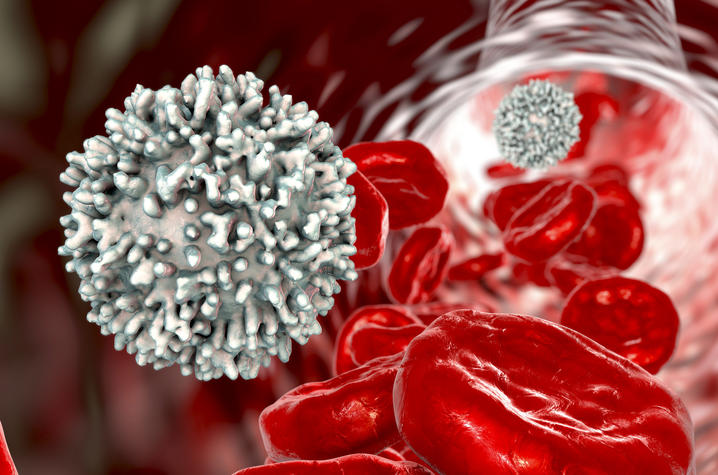

B cells are a type of white blood cell that makes antibodies. Less known and studied, however, is that B cells can produce neurotrophins that regulate the development and growth of neurons in the brain.

An ischemic stroke is the most common type of stroke that happens when an artery in the brain becomes clogged, typically by a blood clot. After ischemic stroke, it is well-known that B cells travel to the site of the stroke as part of the immune response. But this new study shows that B cells may also move into multiple areas of the brain – both injured and uninjured.

“This is rather unique because it broadens our idea that we need to look at other areas of the brain when studying stroke,” says Ann Stowe, UK associate professor in the Department of Neurology and senior author of the study. “These areas are really critical for functional recovery so they could potentially be targets for drug development or therapies.”

Researchers studied the post-stroke recovery of mice and through whole-brain imaging saw that B cells not only migrated to the infarction, or site of the stroke, but to other areas supporting motor and cognitive recovery. Mice with depleted B cells experienced reduced recovery in these areas, confirming these findings.

The results could lead to new therapeutic avenues for stroke patients. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that stroke is a leading cause of adult disability and the fifth leading cause of death in the U.S. Currently, there are only two FDA-approved treatments for acute stroke and no effective therapeutics to promote long-term repair in the brain after stroke damage.

“This study suggests that B cells might have a more neurotrophic role,” Stowe says. “Hopefully from this, we can better understand the inflammatory processes after stroke – and long term, possibly identify what subsets of immune cells can support stroke recovery.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.