Leap Day legacy: The remarkable life of UK’s oldest living alum born on Feb. 29

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 29, 2024) — Today is Leap Day — the day that only occurs once every four years on Feb. 29. Born out of the intricacies of the Julian and Gregorian calendars, Leap Day serves as a corrective measure, keeping the calendar years in sync with Earth’s revolutions around the sun over time.

It comes as no surprise then that those who happen to be born on Feb. 29 have the rarest birthday one could have — only getting to celebrate their “real birthday” once every four years. According to the History Channel, it’s estimated only five million people around the world have this birthday.

On this 2024 Leap Day, the University of Kentucky is celebrating all the Wildcats who can call this unusual day their birthday, which includes just 14 current students and eight employees. And out of more than 280,000 known living UK alumni around the world, only 157 of them were born on Leap Day, or about .05%.

The oldest of those 157 alumni is 1949 UK graduate Charles E. Whaley. Born in 1928, Whaley is 96 years old today, although he is celebrating only his 24th actual birthday.

“A Leap Year birthdate makes you part of a select crowd since most people are stuck with the standard kind,” Whaley said. “I enjoy pointing out that I'll be only 24 on Feb. 29.”

A fun fact to share, certainly, but anyone who has had the pleasure of getting to know Whaley can tell you that his birthday is actually one of the least interesting things about him. Born in a small farm town in Northern Kentucky, Whaley’s education at UK helped set him on a path to an extraordinary career in journalism and continued education. Along this path, he encountered life-altering experiences and forged meaningful connections with remarkable individuals.

On this Leap Day, Whaley’s journey serves as a testament to the transformative power of taking leaps of faith and embracing opportunities.

***

Born and raised in the farming community of Williamstown, Kentucky in Grant County, Whaley says the prospect of college wasn’t attainable for most. Like so many others in his town, his parents had left high school before graduating to tend to farming and family.

Whaley had no plans for attending college but was such a high-achieving student at Williamstown High School that the University of Kentucky took notice.

“I was the valedictorian and drum major of my high school marching band,” Whaley said. “UK at the time offered freshman scholarships to top high school graduates. My post-high school plans were hazy. The UK scholarship settled things for me.”

So Whaley was off to Lexington, as a first-generation college student. He declared a major in journalism in what was then the Department of Journalism (now the School of Journalism and Media in the College of Communication and Information).

“Journalism gave me a portal to all sorts of experiences, as did the range of extracurricular activities that attracted me,” he said.

During his time at UK, Whaley was editor of the Kentuckian (the UK yearbook), a Phi Beta Kappa and was awarded UK’s prestigious Sullivan Award. He also served as president for a host of other organizations, including the student union, his fraternity Sigma Phi Epsilon, SuKY (UK’s spirit club) and other honorary groups, including Omicron Delta Kappa.

Whaley graduated from UK in 1949 — a year that holds special significance for the university, as Lyman T. Johnson led a successful court victory that helped to overturn the Kentucky Day Law and result in integration at UK. While Whaley did not know Johnson personally at the time, he would meet and get to know him later in life. Read more about UK’s commemoration of 75 years of integration here.

After earning his journalism degree from UK, Whaley went on to earn his master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University — a class limited to only 50. While living in New York City, Whaley discovered a passion for the theater and met many interesting people, including Nelle Harper Lee, who he worked with during a summer job at “School Executive” magazine. Lee would later go on to write the classic American novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

After completing his master’s degree, Whaley was hired by the Courier Journal in Louisville as a general assignment reporter. But in 1950, just six months after joining the CJ, Whaley was drafted for U.S. Army service during the Korean War.

He was sent to Fort Knox for basic training but ended up not being sent to Korea. Instead, he was kept at headquarters to work in public information — the Army’s form of journalism — interviewing visiting dignitaries and writing articles that were published by the CJ, Kentucky Business and other outlets.

“I once took a visiting Congressman inside the gold vault made famous by James Bond and those real gold bars were right in front of me,” Whaley recalls.

The Courier Journal reported at the time on Whaley’s outstanding journalism work for the Army. He received multiple letters of praise from top generals, including Maj. General I.D. White, who spoke of Whaley’s “clearly outstanding ability as a journalist and creative writer.” General Mark W. Clark complimented an article Whaley wrote for the way it “vividly points up the fact that military installations always benefit surrounding civilian communities.” A third letter, much like the other two, came from General J. Lawton Collins, chief of staff of the Army.

Whaley also continued to meet interesting people in the Army. He became good friends with a man named Bill Butterworth, who would go on to become a best-selling author of dozens of military and detective novels under the pen name W.E.B. Griffin. Griffin would often drop variations of Whaley’s name in his works, such as “Col. C. Edward Whiley.”

After completing his U.S. Army service in 1952, Whaley returned home to Louisville — and the Courier Journal — to resume his career, still in its early stage. But by a small twist of fate, the next major chapter of his life was about to begin.

Marshall Scholarship

Besides having a Feb. 29 birthday (and being the oldest UK alumnus with that birthday) Whaley holds another, far more impressive distinction. He is the oldest living — and UK’s first — Marshall Scholar recipient.

The Marshall Scholarship is widely considered to be one of the most prestigious scholarships for U.S. citizens. For 70 years, the program has offered college graduates the opportunity to study at any university in the United Kingdom.

Back in 1953, Whaley learned about this new program in the most unlikely of places — a trash can.

“On one slow news night I happened to spot a news release on top of the city editor's wastebasket about a new British government graduate scholarship for American students in gratitude for U.S. Marshall Program aid following World War II,” he said. “It was equivalent in value to the Rhodes Scholarship, but recipients could apply to attend any university in England, Scotland or Wales for two years with possible extensions.”

On a whim, Whaley decided to apply to the program. He was then accepted into the inaugural class of 12 Marshall Scholars in 1954. At 26 years old, Whaley set sail across the Atlantic to the United Kingdom to begin his two-year study program at the University of Manchester.

“I chose to study at Manchester, because at that time the Manchester Guardian was located there (it is now The Guardian in London),” Whaley said in a 2023 interview with the Association of Marshall Scholars (AMS). “I wanted to know all the writers at the Manchester Guardian, since I was a newspaper man. I did get to know them. They came to parties at my house. It was a great experience.”

Since he was an avid reader, who often wrote book reviews for the CJ, Whaley chose to study English literature. For his thesis, he focused on works by poet and novelist Thomas Hardy. During his research, he got to know Hardy’s former secretary, May O’Rourke.

“I ended up spending some time with May, and she gave me a copy of her little monograph about her time with Hardy,” Whaley recounts in the AMS interview. “She signed it for me. Perhaps these things could be classified as frills, but for me they deepened the experience and brightened it.”

During his time in the United Kingdom, Whaley also had opportunities to travel across England and other countries in Europe with fellow scholars, taking in theater productions and writing reviews.

Whaley also made several new friends and acquaintances during this time. One stormy night after a party in Croydon, Whaley and another fellow Marshall Scholar, Carol Edler, were stranded because of heavy rainfall. They ended up staying the weekend at the home of Edler’s classmate — Seretse Khama, the exiled King of Bechuanaland (now Botswana), and his wife and children. Khama even lent Whaley his pajamas to sleep in during their stay.

“Sleeping in the king’s pajamas was a unique experience for me,” Whaley said in the AMS interview.

After finishing his second master’s degree two years later, Whaley stayed involved with the Marshall program, serving as secretary-general of the AMS (1965-1971), as well as on the Mid-Eastern Regional selection committee to interview and recommend scholarship applicants. In 1989, while attending a 35th anniversary celebration of the Marshall Scholarship program in Washington D.C., Whaley was greeted by Charles III (then Prince of Wales, now King of the U.K.) at the British ambassador’s residence.

The AMS reported that Whaley received high praise from Prince Charles, who politely told him that he “has aged very well.”

Journalism power couple

After finishing his Marshall scholarship in 1956, Whaley returned home to Louisville, Kentucky, resuming his job at the Courier Journal.

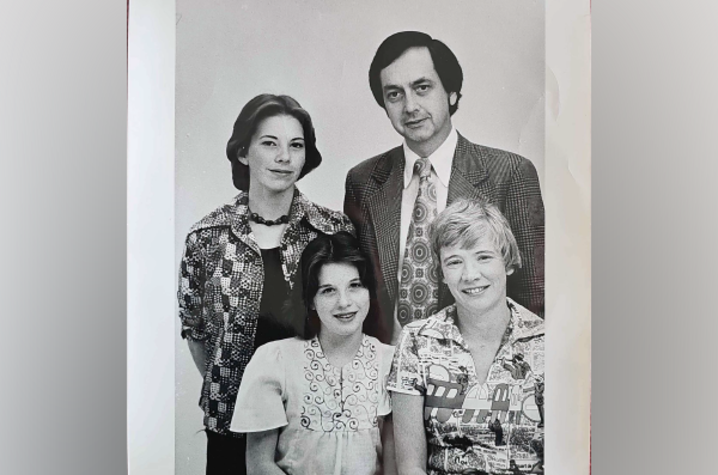

It was during this time when Whaley would meet his future wife, the late Carol Sutton, a distinguished American journalist who was then editor of the women’s section for the Courier. The two married in 1957 and would later have two daughters, Carrie and Kate.

Sutton later became managing editor of the CJ in 1974, making her the first woman to lead a major daily American newspaper in the U.S. This distinction led Time magazine to include her on its 1976 “Women of the Year” cover, representing her notable achievements in journalism.

Under her leadership as editor, the CJ won multiple awards for public service and school desegregation in Louisville. At the same time, Whaley also became an award-winning reporter for his coverage of integration (and the resulting campus riots) at University of Mississippi in 1962. Amid chaos and violence, including an encounter with a body of a fellow reporter who had been fatally shot, Whaley continued to cover the riots from a motel near campus and sent them, by telegram, to the CJ.

At the same time, Sutton wrote a long-form editorial about the Ole Miss events, placing them in the context of Mississippi’s longer history with racial issues.

“It was flawless, deep reporting that stands the test of time,” Whaley said about his wife’s work.

Whaley and Sutton both had passions for advocating for educators and education in Kentucky. Whaley would eventually go on to become the education editor for the CJ — a role that led him to receive a national award from the Education Writers Association for “clear and comprehensive” coverage of education in Kentucky. In 1964, he began working for the Kentucky Education Association (KEA) as director of research and information. In this role, he helped bring more equity and support to educators across the Commonwealth, earning him the Lucy Harth Smith-Atwood S. Wilson Award for Civil and Human Rights in Education (for which he was praised by former UK student, and his new friend, Lyman T. Johnson). From 1982-85 he served as KEA’s director of communications.

It was during this time in 1984 when, tragically, and only 10 years after being named managing editor of the Courier Journal, Sutton was diagnosed with lung cancer. She died in 1985.

Just prior to her death, she was inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame.

She was not a native Kentuckian like Whaley, but a St. Louis native and University of Missouri School of Journalism graduate. However, Kentucky would become her adopted state — a place she deeply understood and loved.

“Carol was the warmest, most genuine human being you could ever meet,” he said. “Her smile was dazzling and her conversation engaging. Her interests were many and she was a quick study who could put stories together in attention-getting ways. Carol paved the way for other female journalists at her newspaper and those in other states to manage news operations.”

To honor her life and legacy, Whaley, along with family and friends, created the Carol Sutton Endowed Scholarship at the University of Kentucky to support journalism majors.

After her death, Whaley knew life in Louisville would be very different without her. Their two daughters were now adults. So when a national search committee recruited him to be executive director of the American Lung Association of San Francisco, he decided it was time to make a career shift.

Whaley notes that practically all news people “in his day” smoked, including himself. But after he learned of the dangers of smoking in the 1960s, he quit cold turkey. But for others, that’s not so easy. Whaley wanted to change this.

“With the lung association I was doing something that helped fight the dreadful addiction to smoking that ended Carol's life far too soon,” Whaley said. “We accomplished a lot through workplace and public space smoking bans, second-hand smoke awareness and prohibitions, public education forums, and lobbying in Sacramento for grants and special programs.”

Whaley served in this role in San Francisco for nine years until his retirement in 1993.

He then, once again, returned home to Kentucky.

***

Whaley has continued to keep busy during retirement, spending the past 30 years writing book and theater reviews and op-eds for the Courier Journal. He is a longtime member of the American Theatre Critics Association, the Society of Professional Journalists and the Public Relations Society of America, and has served in leadership roles for these organizations throughout his life.

He has lived in the same house in Louisville’s historical Cherokee Triangle Preservation District since the late 1950s, a place with a history of famous former residents he enjoys researching. Read more about them and other interesting people he's hosted in his home here.

Whaley says his advice for a long and rich life is to always have something to look forward to. For him, that hasn’t been hard to do.

“With that outlook, I seldom get bored,” he said. “There is always something to whet and keep my interest, be it books, films, plays, people, music, travel, parties, etc.”

While many of the events and experiences in his life happened by chance, Whaley’s drive to seek opportunities and continue learning has played an important role in setting the course of his life. This was evident nearly 80 years ago, when the University of Kentucky took notice of a hard-working high school student in Northern Kentucky and offered him a scholarship.

“UK awakened me to possibilities, offering a glorious academic banquet, and I took every opportunity to enjoy it to the fullest,” he said.

As for his big 24th birthday plans? Whaley says there will be a party at his house with his daughters, old friends and extended family members (including a grandson, Casey Orman, who is also a graduate of the UK College of Communication and Information).

“I wish I could think of some profound thought to share about what comes after this momentous birthday,” Whaley said. "'Keep calm and carry on’ got the British through World War II and still works fine. But what does it for me is James Taylor's gently accepting song ‘The Secret of Life.’ The secret? Enjoying the passage of time. Celebrate being alive.”

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.