Op-Ed: New Liver Organ Policy Should Be Stopped Before It’s Too Late

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 24, 2020) – A rushed proposal that became federal policy across the country this month will increase the cost and decrease access to life-saving care for patients in dire need of a liver transplant across much of the South and Midwest.

The result: people in Kentucky and largely rural areas of the country will be more likely to die because they won’t receive the care they need or would have had access to before this month.

As health care professionals and leaders of the state’s two academic medical centers, we are doing everything we can to delay or reverse this detrimental policy.

Here’s what is happening and what is at stake for Kentucky:

On Feb. 4, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) -- based on a recommendation from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) -- implemented a new policy for how livers are allocated around the country for potential transplant. The OPTN sets transplantation policy at the direction of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

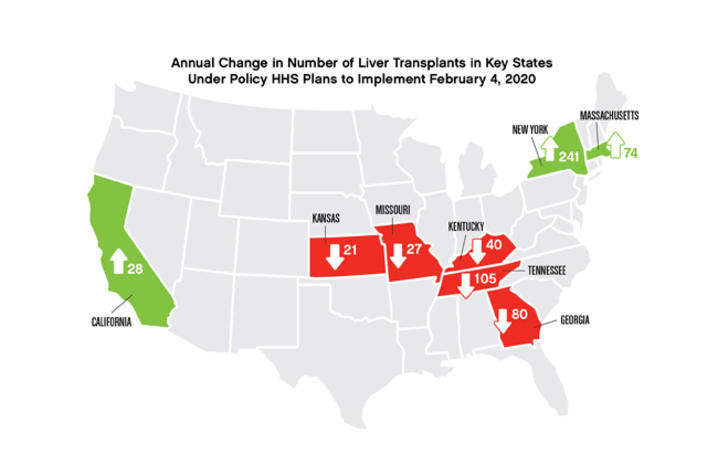

The basic framework of this policy would mean more organs in rural states, like Kentucky, would be sent to larger inner-city medical centers that have higher populations. The idea was to create a policy that ensured more critically ill patients (within 500 nautical miles) received access to livers, rather than the patients in closer proximity.

While the transplant policy is well-intentioned, the fact is the governing board creating and directing the policy is dominated by officials from large urban, coastal areas. The resulting policy benefits those areas.

The process creating this program was rushed and the policy is deeply flawed.

Even the framers of it concede there will be nearly a 30 percent drop in liver transplant volume in Kentucky as a result of this policy. We believe the drop will be even more significant, on the order of 40 percent.

Kentucky, as so many of us know, has a higher mortality rate for chronic liver disease such as cirrhosis than the national average. In rural areas of our state, the rate is even higher as access to care is more limited.

Several things – all negative -- will occur in Kentucky and other rural areas of the country:

- This new policy will decrease access to livers for transplant even further.

- It will increase costs, the result of a more inefficient system because of rising costs for flights, fuel and transportation for Kentuckians and others who will have to travel farther to receive transplantation services.

- It will result in longer waiting periods and poorer health outcomes for Kentuckians and others who have to wait longer for donated livers.

- Others, who have to wait and who don’t have time, will be more likely to die.

We stand with a network of academic medical centers throughout the South and Midwest – Emory University, the University of Kansas, Indiana University, the University of Michigan, Vanderbilt University, the University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University and Washington University in St. Louis – that have filed a federal lawsuit, asking to prohibit the federal government from implementing the policy.

Although the federal court in Atlanta declined to stop the government from implementing the policy on Feb. 4, the fight is far from over.

We are continuing to challenge the policy and asking the court to order the federal government to seek additional input. Ultimately, the federal government must craft something more equitable for everyone in America, not just those in larger cities or on the coasts.

We have received support from many federal policymakers, led by Senate Leader Mitch McConnell.

However, we continue to appeal to others – from the White House to the U.S. Secretary of HHS and other elected officials – to do what they can, with the voices and power they have, to prevent or reverse implementation of this ill-advised and biased approach to transplantation care.

We can still do the right thing. We are not done fighting and making our voices heard on behalf of those who depend upon us for life-saving care.

We need, and respectfully ask, those in power to listen and act.

For so many people, time is running out.

###

Tom Miller is chief executive officer of UofL Health; Kelly M. McMasters, MD, PhD is Ben A. Reid, Sr., MD Professor and Chair The Hiram C. Polk Jr., MD Department of Surgery, University of Louisville School of Medicine

Mark Newman is executive vice president for health affairs at the University of Kentucky; William B. Inabnet III, MD, MHA, FACS is the Johnston-Wright Endowed Professor and Chair of Surgery, UK College of Medicine, UK HealthCare

As the state’s flagship, land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky exists to advance the Commonwealth. We do that by preparing the next generation of leaders — placing students at the heart of everything we do — and transforming the lives of Kentuckians through education, research and creative work, service and health care. We pride ourselves on being a catalyst for breakthroughs and a force for healing, a place where ingenuity unfolds. It's all made possible by our people — visionaries, disruptors and pioneers — who make up 200 academic programs, a $476.5 million research and development enterprise and a world-class medical center, all on one campus.