UK Doctoral Student Assists Ford with Emissions Research

LEXINGTON, Ky. (May 31, 2010) − Vence Easterling is mixing it up with the big boys.

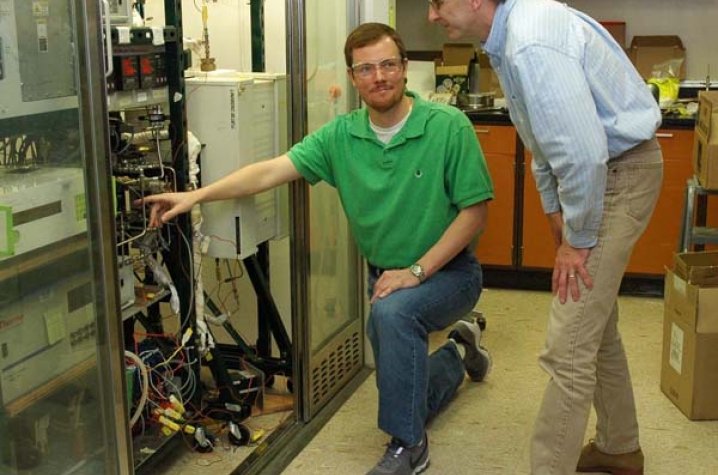

A University of Kentucky chemical engineering Ph.D. candidate, Easterling has spent nearly two years performing research with Ford Motor Co. scientists seeking new, more efficient ways to cleanse vehicle emissions.

Their focus at the moment is on a catalytic converter system that combines two existing approaches to not only eliminate nitrogen oxide emissions but also help to lower emissions of carbon dioxide.

“It could be one of the most significant advances in emission control technology since the catalytic converter was introduced in the 1970s,” says Easterling, who uses a sophisticated mass spectrometer to probe the chemistry occurring in the converter system.

Easterling and his mentors at Ford Research and Innovation Center in Dearborn, Mich., are building on a system already in limited use in some cars in Europe and Japan.

They also are in direct competition with other U.S. vehicle manufacturers engaged in similar research.

"A lot of research groups are going after this. It's a matter of who gets there first," Easterling says.

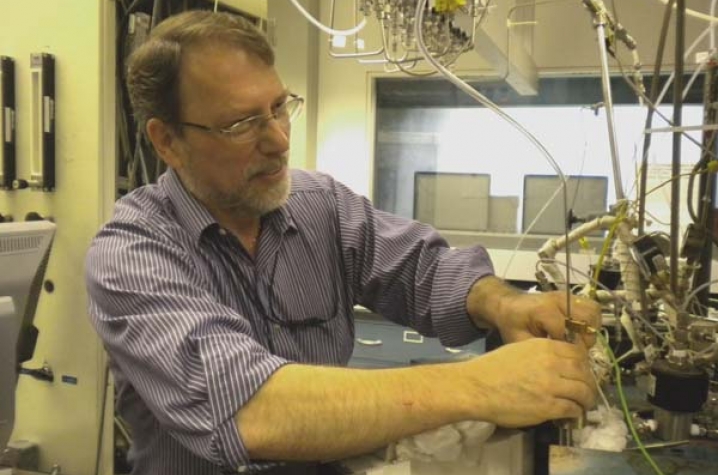

His faculty mentor at the UK Center for Applied Energy Research, Mark Crocker, says a key goal in cleaning vehicle exhaust involves eliminating nitrogen oxides (NOx) from lean-burn gasoline and diesel engines. These engines are able to use fuel more efficiently than conventional gasoline engines and hence emit lower amounts of carbon dioxide.

"The problem is getting rid of the nitrogen oxides and unburned hydrocarbons," Crocker says.

Researchers already have developed a "lean nitrogen oxide trap" (LNT) catalytic converter that traps NOx temporarily and then splits the nitrogen's bond with oxygen, freeing both into the atmosphere. Since nitrogen already comprises most of the gases that make up air, it causes no harm.

However, this system contains expensive precious metals such as platinum.

Ford Research and Innovation Center scientists, including Mark Dearth, are investigating ways to combine the LNT system with a selective catalytic reduction catalyst (SCR) approach. (Easterling spends several weeks a year at the Dearborn center, as well as with researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. The rest of his time is spent at the UK Center for Applied Energy Research with Crocker.)

"The SCR system is already in use on stationary power plants and farm equipment, as well as on a Ford pickup, to scrub emissions," Easterling says.

"What we're doing is using both the LNT and SCR systems. By combining the systems, Ford researchers have found that the amount of precious metals in the LNT catalyst can be decreased, resulting in cost savings for the overall system.

"We're also finding a synergistic effect of using both the LNT and SCR systems. They work better in conjunction than they do separately," Easterling says.

Dearth, the Ford Research and Innovation Center scientist who works directly with Easterling, says the mass spectrometer used in the project is highly precise. "It's a unique piece of equipment that offers its analysis second by second -- or even faster."

The new system they're studying is showing great promise for cleansing both NOx and sulfur emissions, Dearth says. "Sulfur is a problem in any vehicle's exhaust. It's a poison to after-treatment systems," he says.

Dearth says he and Easterling had an almost instant bond when the doctoral candidate joined the project in 2006. "We came out of similar backgrounds. We both sought our advanced degrees after a number of years in the workforce."

Dearth got his doctorate when he was 35. Easterling returned to UK in 2006 after having graduated from UK in 1999 and spending several years working for AK Steel and U.S. Steel as a blast-furnace shift foreman.

This project, Easterling and Dearth agree, is far more interesting work.

"We're not reinventing the wheel. We're just making it roll a little better," says Easterling.