Locals Want to Return to Harlan County

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Sept. 9, 2011) — What do you want to be when you grow up? That's exactly what Tricia Dyk, the University of Kentucky's Director of the Center for Leadership Development, asked 4th-8th grade students in a Harlan County 4-H program almost 20 years ago.

Last fall, Dyk approached sociology doctoral student and Community & Leadership Development research assistant Jess Kropczynski about the mass amounts of data she had from her past work in the area.

"Dr. Dyk had the idea that we could follow up with the students she originally surveyed," said Kropczynski, also a sociology graduate student in the College of Arts & Sciences. "At this point, they'd be in their late 20s or early 30s; most would have pursued careers."

Dyk and Kropczynski wanted to know what had actually happened to the surveyed students, who were asked for basic information, but also about the presence of technology in their homes, school participation, educational and career aspirations and measures of self-esteem, among other topics.

Dyk received a grant through the UK Center for Poverty Research to help her track down those surveyed, and her study, titled "Pathways to Adulthood: Opportunities and Challenges for Harlan County Youth Employment Success," has generated some surprising results.

"Through the program, Dr. Dyk encouraged students to learn more about different career paths through in-class activities and field trips, while surveying them to see what they aspired to become," said Kropczynski. "She also asked what students had to do to get there and what could stand in the way."

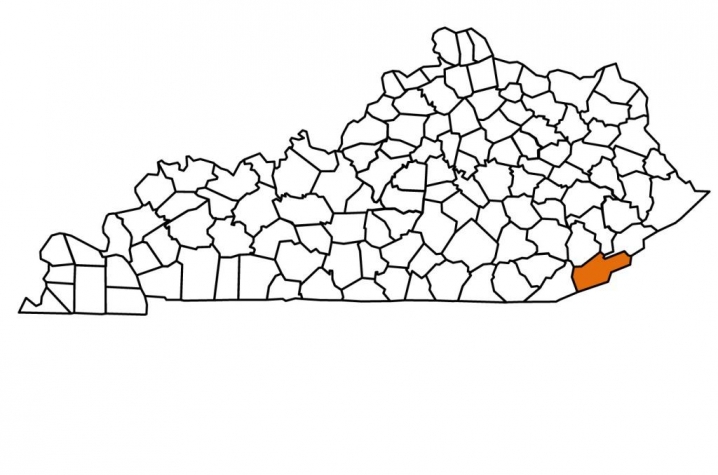

Based upon local need and the availability of resources, Harlan County was selected as a program site by the Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service under the Literacy and Technological Literacy Area of Youth at Risk.

By focusing on career preparation and employability, the Harlan Youth Employability Program was designed to build a connection between high risk youth and the work world.

According to Kropczynski, many of the children surveyed in 1991 were quite candid in describing the obstacles that they faced, citing drugs, alcohol and pregnancy as possible barriers to a future career.

In looking back at scholarly literature, the concept of rural brain drain can easily be applied to areas like Harlan County. "This is typified by the best and the brightest of these areas leaving home for education and career and never returning," Kropczynski said. "For this reason, rural communities often spend a disproportionate amount of effort, resources and training on the children that are not likely to stay; and the ones who stay often get little attention."

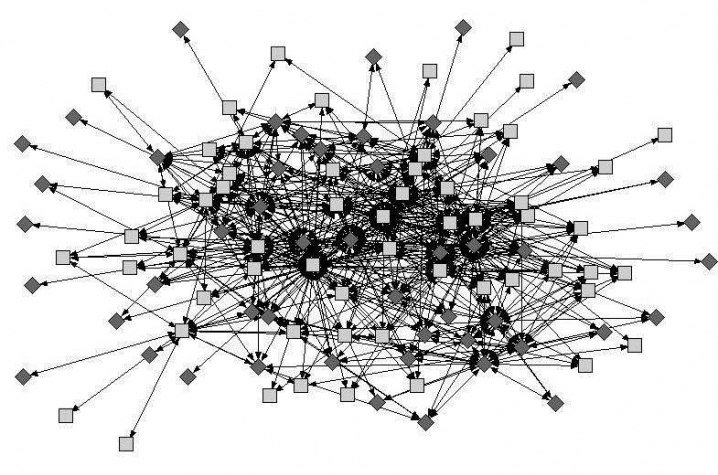

Catching up with Harlan County's elementary students from the early 1990s was difficult, but with the assistance of Facebook networks, a Harlan County librarian and a preacher, Kropczynski got to work.

"A few people thought that I was trying to sell them something, some didn't remember the survey at all, but many were really enthusiastic and wanted to see what they had written," she said.

Kropczynski was able to send back the original survey to about 24 percent of the original survey participants with the request to update her on what they were doing now.

"We tried to figure out which people were most instrumental on the pathway to a career," said Kropczynski. "And for those that went away to college, we were curious if they found jobs outside of their community or if they returned to Harlan and why."

While many involved in rural education research discuss rural brain drain, Dyk and Kropczynski's research developed a new category.

In addition to the "achievers," or locals who succeeded and left Harlan County permanently, "reluctant returners," those who failed and came back; "stayers," those who took over a family business or got a job during high school and remained; and "seekers," those who wanted to leave but didn't have the means to, Kropczynski focused in on a group that she and Dyk labeled "intentional returners."

Intentional returners succeeded in their respective careers and deliberately decided to come back home. "Some Harlan County natives knew they were mapping a career path, and returning home was a part of the plan," Kropczynski said.

The group Dyk surveyed in 1991 was high-performing as a whole, which bodes well for the future of Kentucky counties known for rural brain drain. "It's optimistic," Kropczynski said. "A lot of people from Harlan County wanted to come home and make their community better."